A Critical Analysis on the Effects of Pornography

How harmful is pornography? The research is more nuanced than what people believe it to be.

I consider this review to be a comprehensive examination of the impacts of pornography, presenting unique arguments that are rarely found in other sources but hold significant relevance to the ongoing debate. It represents the culmination of extensive research conducted over the course of several years, aiming to provide a comprehensive resource for arguments and discussions on the topic. I am committed to updating the review as new studies come to my attention through ongoing research.

Chapters:

Introduction

Self-Reported Effects

2.2: Children

Effects on Relationships

3.2: The Impact of Pornography on Real Sexual Encounters

3.3: Processing into Relationships & Marriages

3.4: Effects on Relationship Outcomes

Sexual Functioning

4.2: Porn-Induced Erectile Dysfunction

Psychological Well-Being (Paywall)

Behavior and Attitudes

6.2: Aggression

6.3: Attitudes Towards Women

6.4: Criminality

The Pornography Industry

7.2: Sex Trafficking

7.3: Violence in Pornography

7.4: Well-being of Pornography Actors

7.5: Onlyfans

Pornography Addiction

8.2: Defining “Addiction”

8.3: Pornography as a Drug

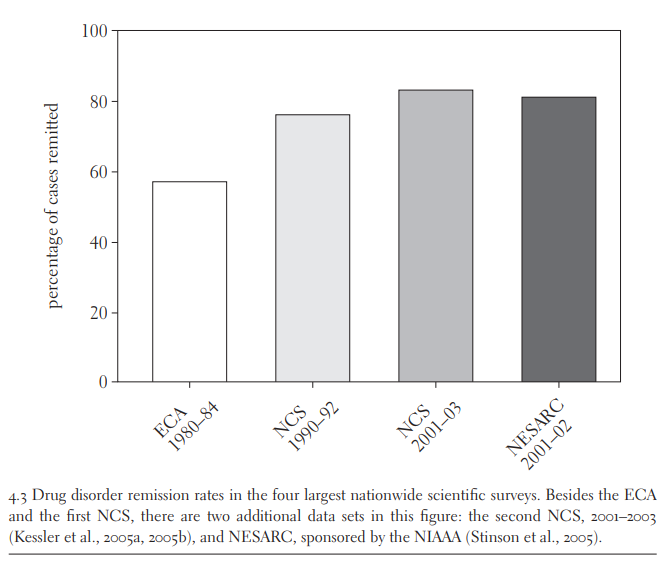

8.4: Ephemeral Nature of Addiction

Reboot Programs

9.2: Issues with “Reboot” Claims

9.3: Reboot Users and Well-Being

Introduction

In the early 1980s, concerns about the proliferation and accessibility of pornography in the United States led to increased public debate on the subject. The Reagan administration, known for its conservative stance on social issues, appointed a commission to study the effects of pornography and make recommendations on potential policy changes. The Meese Commission conducted extensive research and analysis over a two-year period. The report would be called The Meese Report (1986).

The Meese Commission conducted extensive research and analysis over a two-year period. The report concluded that pornography posed significant social, legal, and personal harms. It argued that pornography could lead to a variety of negative consequences, including an increase in sexual violence, the objectification of women, and the erosion of traditional family values. The report emphasized the need for stricter enforcement of obscenity laws and the implementation of measures to protect vulnerable individuals, such as children, from exposure to explicit materials.

The Meese Report generated considerable controversy and debate. Supporters praised its findings and recommendations, seeing it as a call to action against the perceived negative effects of pornography. They believed that the report provided a basis for tighter regulation of the adult entertainment industry and the protection of individuals from harmful material. Critics, however, raised several concerns about the report. Some argued that it had a biased agenda, reflecting the moral views of the conservative Reagan administration rather than objective research. Critics also pointed out methodological flaws in the report's research and questioned the validity of its conclusions. They argued that the report's focus on obscenity laws and increased regulation infringed on First Amendment rights, such as freedom of speech and expression.

In Nobile and Nadler’s (1986) work United States of America vs. Sex: How the Meese Commission Lied About Pornography, Nobile and Nadler argue that the Meese Commission's findings were based on flawed research and that the commission's conclusions were politically motivated. For example, one study that the commission cited found that exposure to pornography led to an increase in aggressive behavior in men. However, the study was later found to be flawed because it did not control for other factors that could have contributed to the increase in aggressive behavior, such as men's exposure to violence in other forms of media. The Meese Commission cherry-picked the data that it used to support its conclusions. For example, the commission cited a study that found that exposure to pornography led to an increase in rape fantasies in women. However, the commission did not mention that the study also found that exposure to pornography did not lead to an increase in actual rape, and made no mention of data displaying that exposure to pornography did not lead to an increase in violence against women. (See Berger 1991 for more information and a review of The Meese Report.)

Overall, the Meese Report was influential in shaping the public discourse on pornography in the 1980s and beyond. While some of its recommendations led to increased enforcement efforts and changes in legislation, others faced legal challenges and were not widely implemented. The report remains a topic of discussion in debates surrounding pornography, censorship, and the balance between protecting individuals and preserving constitutional rights.

The ghost of the Meese Report continues to live on in contemporary times. In January 2023, two Arkansas senators proposed a bill that would require digital identification to access pornographic material online to create liability for the production or distribution of material considered “harmful to minors on the internet” (THV11 Digital 2023). The Protection of Minors from Distribution of Harmful Materials Act bill states that pornography is harmful towards adolescents. Pornography is considered a “public health crisis”, leads to the hyper-sexualization if minors, causes damage to one’s psychological well-being, promotes pornography addiction, impacts brain development and function, leads to “problematic” and “risky” sexual behavior, and causes deviant sexual arousal (Protection of Minors from Distribution of Harmful Materials Act, Senate Bill 66, 94th General Assembly, 2023: 2). This bill is reminiscent to a law passed in Louisiana at the start of 2023 that requires ID to access pornographic content online (Pollina 2023), with the passed law also making the same statements on pornography’s effects as the Arkansas’s bill (ACT No. 444, House Bill No. 142, 2022: 2).

Following the proposed Arkansas bill, Utah state senator Sen. Todd Weiler has proposed a similar bill requiring online identification to watch pornography online (Schott 2013). Utah’s fight against pornography is not new as it was labeled a “public health crisis” in 2016 (Stuckey 2016). In fact, Weiler claimed that, at the time, he was “...not advocating action by the government.” After the proposed Arkansas bill, however, Weiler took government intervention as the next step against pornography. The panic against pornography is not restricted to a small number of states. As Quinn (2016) notes, many other states have adopted the view that pornography is a public health crisis, which includes “Arkansas, Arizona, Florida, Idaho, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, Montana, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah and Virginia.” Even France has required verification for watching online pornography content (Samuel 2023).

Where are legal bodies getting the idea that pornography is harmful, though? As Quinn remarks, “Most of the passed resolutions were adopted by model legislation written by the center, which didn't respond to multiple requests for an interview.” The center refers to The National Center on Sexual Exploitation (NCOSE), previously known as Morality in Media. Since its inception, NCOSE has been anti-pornography. According to their own website, the organization’s mission was to “counter the effects of pornography” on children and adolescents, and to enforce obscenity laws (National Center on Sexual Exploitation). A look through NCOSE’s online history page displays that they supported the findings of the Meese Report and have decided to take their anti-pornography crusade online since “Many of the children coming of age in this decade are exposed to voluminous amounts of pornography.” However, despite the name changes, NCOSE is not simply against pornography but has also waged a war on sex education (Heins 2007: 176) and same-sex marriage (Cahil 2006). However, as other organizations have noted, NCOSE uses "misleading 'research reports' to fabricate a false medical consensus about the harms of pornography" (in Chapman-Schmidt 2019). Brown (2015) echoes a similar statement, “Several recent studies have offered results opposite those NCSE claims.” (See Heins: 175-176 for more examples from NCOSE’s early days.)

Writing for Fox News, Marcus (2022) makes a similar case against pornography and its harm to children as NCOSE. Marcus argues that “The United States should seek to ban hardcore pornography from the internet. The most obvious reason to do this is that children are inundated with an avalanche of smut.” Leonardi (2021) in The National Review says when discussing a ban on pornography, “But there is a middle ground, one that gives parents greater control over how they choose to raise their children and protects the mental and psychological health of those children: banning free online porn.” Conservative commentator Matt Walsh also argues for the banning on pornography because of its “harmful” effects on children (Walsh 2019) — with some of the studies and arguments he makes even being indirectly responded to in this article.

Groups and star individuals have also followed in the footsteps of NCOSE, also using science [emphasis added] to bolster their claims. Fight The New Drug seems to be one of the more popular anti-pornography groups, being referenced in many anti-pornography articles and works. Based on their name, they believe pornography is as harmful as drugs, and have multiple articles detailing how pornography is harmful through multiple citations. Akin to Fight The New Drug, Your Brain on Porn also acts as a one-stop-shop for resources on how pornography is harmful. Created by Gary Wilson, a dubious figure in his own right, Wilson attempts to drown the reader in multiple sources on how pornography is harmful. A look at some of the studies cited by Wilson, however, displays his misrepresentation of these studies — some examples to be included in this article, but also deserving of a standalone work. Wilson makes extraordinary claims, making causal implications from correlative analysis, and seemingly being a scholar in multiple scientific areas, despite not grasping an understanding of how to read simple social science papers, and having a tendency to refer to his critics as being in bed with the pornography industry.

Exodus Cry is another anti-pornography group hiding behind the mask of being anti-sex trafficking. The group is a heavily religious organization, being against abortion, and sex work, too. As they state in their website, “Porn is rife with the rape, trafficking and exploitation of men, women and children, and propagates a culture of sexual objectification.” Exodus Cry spawned Traffickinghub, spearheaded by Laila Mickelwait, a character to be discussed later in the article. According to Mickelwait’s Traffickinghub movement, the online pornography giant Pornhub was guilty of promoting sexual abuse of minors and hosting illegal sexual content. Through unfortunate cases, Mickelwait was able to get Visa and Mastercard to be blocked from being used on the site (Bently 2020). The end goal was to have Pornhub banned, however. The use of blocking payment was the first step to a larger war against pornography.

After the successful attack on Pornhub, Exodus Cry targeted Onlyfans, the online site where users can post sexually explicit content for subscribers. They attempted to payment providers and banks to stop allowing users to use their services on Onlyfans, with Onlyfans almost going as far as to ban sexual content on their site (Stokel-Walker 2021; See Hochman 2021 for a right-wing perspective on the issue ). Despite their failures, Exodus Cry, NCOSE, and Laila Mickelwait continue their crusade against pornography.

Smaller figures have also helped the scene, but one figure, in particular, has provided strong ammunition for years. Nicholas Kristof is an American journalist and political commentator and has also spent years arguing against sex work and pornography. It’s no surprise his articles have been used as evidence against sex work and the pornography industry. In his influential New York Times article that was used by Mickelwait for her Traffickinghub movement, Kristof said

Its site [Pornhub] is infested with rape videos. It monetizes child rapes, revenge pornography, spy cam videos of women showering, racist and misogynist content, and footage of women being asphyxiated in plastic bags. A search for “girls under18” (no space) or “14yo” leads in each case to more than 100,000 videos. Most aren’t of children being assaulted, but too many are.

Where is this evidence? Who knows. Kristof describes a horrific site, but even he fails to show that this issue is as widespread as he and Mickelwait describe it by saying “Most aren’t of children being assaulted…” and trying to bring back the emotional hit of his sentence by ending it with “but too many are.” While one child having their recorded sexual abuse online is bad enough, it does not justify attempting to paint Pornhub as a resource filled with illegal content. Kristof says, “I came across many videos on Pornhub that were recordings of assaults on unconscious women and girls. The rapists would open the eyelids of the victims and touch their eyeballs to show that they were nonresponsive.” Kristof makes no mention of reporting these videos, or anything that implies he took action, which leads to doubt on the validity of his story.

The reader might wonder why I am being very critical of Kristof’s personal story, but this is because Kristof does not have a good record as a man of honesty. In describing Kristof’s anti-beer crusade, Olson (2012) says if “there [is] a New York Times columnist as insufferably moralistic, or as neglectful of facts that contradict his argument, as Nicholas Kristof?” Focusing directly on Krisotf’s anti-sex work campaigns, Sullum (2012) discusses how Kristof launched a war on the now-defunct site Backpage, where users could find products to buy, sell stuff, find roommates, and even sexual services. Kristof popularized the story of a 16-year-old girl named Allisa, who was supposedly sex trafficked on the site in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Atlantic City. What was not mentioned was the fact that Alissa could not have been on Backpage.

The company adds that Alissa, who testified that she had been compelled to work as a prostitute in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Atlantic City, said she left prostitution in August 2005, and "in the summer of 2005 Backpage.com did not exist in Boston, New York, Philadelphia or Atlantic City."

Facts do not matter to Kristof, and his use of backtracking and saving face is not exclusive to Pornhub. As Sullum notes when talking about how Kristof mentioned Backpage as a site for sex trafficking,

Kristof concedes that "many prostitution ads on Backpage are placed by adult women acting on their own without coercion," and he says "they're not my concern." Yet he cites the National Association of Attorneys General, which routinely equates all prostitution with slavery, to back up his claim that Backpage.com is "the premier Web site for human trafficking in the United States,"

Kristof even attempted to attack Goldman Sachs for having a stake in the site Village Voice Media, which ran Backpage (Sullum 2012b). Kristof argued that because Goldman Sachs had a stake in Village Voice Media, they were complicit in horrific crimes. Sullum (2015) makes a similar case against Kristof as this article, noting that how Kristof’s hyperbolic statements spread without evidence.

Whatever the actual number, Kristof says some of these teenagers are exploited by pimps who take out "ads in which they sell 15-year-old girls as if they were pizzas." How many of those ads have appeared on Backpage.com? Kristof doesn't know that either, but he wants us to think it's a lot. "Almost every time a girl is rescued from traffickers," he avers, "it turns out that she was peddled on Backpage." He mentions two examples.

That anti-pornography activists have a disdain for the facts is not new, as is evidenced by their citations. Perry (2022) found that people with lower trust in science were more likely to support banning pornography. Being a conservative protestant, biblical literalist, and other variables were significantly associated with support in banning porngraphy.

This article seeks to separate fact from fiction for the science of pornography, especially in the contemporary climate where many groups and activists claim that pornography is harmful. For the sake of clarification, those who believe pornography is harmful are labeled as “anti-pornography critics”, although some may not necessarily be against pornography. This is neither a pro or anti-pornography, but a sober look at the facts.

Self-Reported Effects

When examining the impact of pornography on individuals, a distinct dichotomy arises between the assertions made by critics and the accounts provided by individuals when questioned about the effects of pornography. Fight The New Drug frequently presents narratives from individuals who attest to the detrimental effects of pornography on their lives (Fight The New Drug 2019a; 2019b; 2019c). These narratives consistently convey the notion that pornography has only engendered adverse outcomes, without any reported instances of it being beneficial. Such findings are unsurprising, given the singular perspective through which Fight The New Drug perceives pornography. However, upon a closer examination of the available evidence, disparate outcomes emerge in contrast to the assertions propagated by anti-pornography platforms.

Hald and Malamuth (2008) conducted a study involving a sample of 688 Danish participants, consisting of 316 men and 327 women. The researchers employed the Pornography Consumption Questionnaire to assess various factors, including sociodemographic characteristics, sexual behavior, and patterns of pornography exposure. Subsequently, the participants completed the Pornography Consumption Effect Scale/ This scale aimed to measure attitudes towards sex, sexual knowledge, general life satisfaction, attitudes towards and perceptions of the opposite gender, and the perceived impact of hardcore pornography on participants' sexual behavior and overall sex life.

The results of the study revealed that both men and women reported experiencing more positive effects than negative effects associated with their consumption of pornography, with effect sizes ranging from d = .76 to 2.04. Specifically, men were more likely to report greater positive effects in relation to their sex life, general life satisfaction, attitudes towards and perceptions of the opposite gender, as well as attitudes toward sex.

In terms of the impact on women, significant positive effects were reported in relation to their sex life, general life satisfaction, and attitudes towards sex. However, no discernible effect was found regarding women's attitudes towards and perception of the opposite gender. Examining the correlations, it was observed that among men, greater pornography use exhibited a positive correlation with perceived positive effects (r = 0.41, p < .001), displaying a linear trend. This suggests that as pornography consumption increased, individuals reported a corresponding increase in perceived positive effects. Conversely, there was no statistically significant correlation or trend found between greater pornography use and negative effects among men (r = 0.08, p = 0.22).

Similar patterns emerged when examining the effects on women. For women, a positive correlation was observed between greater pornography use and perceived positive effects (r = 0.45, p < 0.01), displaying a linear trend. The perceived positive effects were associated with several factors, including greater pornography consumption, male gender, higher frequency of masturbation, perception of pornography as depicting a realistic portrayal of sex, and an earlier age of first exposure to pornography. On the other hand, perceived negative effects were correlated with male gender, younger age of first exposure to pornography, lower frequency of masturbation, greater pornography consumption, and decreased frequency of intercourse. In a combined analysis of the variables related to positive effects and their correlations, it was found that they collectively explained 30.1% of the total variance. In contrast, the variables associated with negative effects and their correlations accounted for 2.6% of the total variance.

In a related investigation conducted by Hald, Smolenski, and Rosser (2013), the effects of pornography consumption were assessed in terms of cognitive, affective, and behavioral outcomes. The study also examined additional measures, such as exposure to sexually explicit material, positive and negative effects, social desirability bias, compulsive sexual behavior, and engagement in unprotected anal intercourse with male partners.

Results from both samples indicated that pornography use was associated with increased knowledge of various sexual acts, heightened interest in exploring new sexual acts or positions, and greater enjoyment of masturbation. Notably, among homosexual men, a striking majority of 97% reported experiencing positive effects of pornography, while only 3% reported any negative effects. Moreover, the consumption of sexually explicit material was found to significantly correlate with an increased interest in engaging in protected anal intercourse, whereas there was no significant increase in the interest in engaging in unprotected sex.

Regarding specific items assessed, it is noteworthy that "acceptance of your body" was the sole item that displayed a negative effect, indicated by a zero score suggesting a decrease. It is worth mentioning that social desirability did not appear to play a significant role in the self-reported negative effects reported by the participants.

Mulya and Hald (2014) conducted a study involving 249 Indonesian university students (112 male, 137 female) who reported having watched pornography within the past 12 months. The researchers analyzed the data, and Table 3 presented notable findings. The results indicated that both men and women reported significantly larger positive effects compared to negative effects resulting from their exposure to pornography, with effect sizes ranging from d = 0.78 to 1.69. Notably, women reported significantly larger effects in the context of life in general (d = 0.96), while men did not report significant effects (d = 0.13). However, no significant differences were found between men and women concerning positive effects.

Both men and women reported positive effects stemming from pornography in their sex life, with women reporting a stronger effect than men (d = 1.69 for women, d = 1.30 for men). Moreover, both genders reported positive effects in terms of sexual knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes, as well as life in general. Both reported negative attitudes toward sex. Various factors, including relationship status, sensation seeking, sexual attitude, sexual behavior, parental involvement, acceptance of pornography, perceived realism of pornography, and pornography consumption, collectively accounted for 40% of the variance in the positive effects of pornography. In the case of self-reported negative effects, the variables of age of first exposure, acceptance of pornography, perceived realism of pornography, and pornography consumption explained 6% of the variance.

In a study conducted by Miller, Kidd, and Hald (2018), a sample of 312 heterosexual men from community and college settings across various countries including Australia, the United States, Singapore, Canada, the United Kingdom, and other European nations was examined. The study aimed to assess demographic variables, pornography use patterns, and scores on the Pornography Consumption Effects Scale (PCES), specifically focusing on domains such as sex life, attitudes towards sex, life satisfaction, perceptions and attitudes towards the opposite gender, and sexual knowledge.

The findings revealed that the majority of participants reported experiencing positive effects across all domains of the PCES, as measured by both the long version and the short-form version of the scale. While self-reported positive effects outweighed self-reported negative effects, it is noteworthy that the negative effect size, as indicated by the Negative Effects of Pornography Short-Form (NED-SF), was close to two, suggesting a small negative effect. This implies that while some individuals reported problems associated with pornography, the majority reported positive effects.

In summary, the results indicate that most individuals who consumed pornography reported positive effects in terms of their sex life, attitudes towards sex, life satisfaction, perceptions and attitudes towards the opposite gender, and sexual knowledge.

Hesse and Pedersen (2017) conducted a study involving 337 participants who were recruited through online forms and from a research participant pool in a large Western Canadian city. The researchers administered the Falsification Anatomy Questionnaire and the Modified Pornography Consumption Questionnaire to collect data. The objective was to investigate the relationship between the frequency of sexually explicit material consumption, knowledge of anatomy, physiology, and sexual behavior, as well as the effects of sexually explicit material on various aspects.

The findings indicated that the frequency of sexually explicit material consumption did not predict poorer knowledge of anatomy, physiology, and sexual behavior. Both genders reported experiencing more positive effects than negative effects from consuming sexually explicit material. These positive effects were observed in terms of sexual knowledge, attitudes towards sex, sexual behaviors, perceptions and attitudes towards the opposite gender, and overall life quality. Interestingly, the frequency of sexually explicit material consumption was found to predict more accurate knowledge of anatomy, physiology, and sexual behavior.

It was noted that men were more likely to report both more negative effects and more positive effects. However, these negative effects were associated with a higher number of oral, anal, and vaginal intercourse partners. The interpretation of these correlations as negative appears to be influenced by personal values and judgments regarding sexual behavior among individuals.

In contrast to the aforementioned studies, Wright et al. (2017) present a more critical perspective on the effects of pornography. Their meta-analysis encompassed 50 studies examining the impact of pornography on interpersonal satisfaction and intrapersonal satisfaction. The analysis revealed a negative correlation based on all the aggregated effect sizes, indicating that pornography use was associated with decreased interpersonal satisfaction (r = -0.10, p < 0.001). When examining the specific variables, the average effect sizes between pornography use and relational satisfaction were found to be -0.09 and -0.11, respectively. Moreover, the average effect size for pornography use and intrapersonal satisfaction was -0.3. It should be noted, however, that these effect sizes were small and weak. In response to the literature's harm-focused orientation and assumptions regarding causality, Kohut, Fisher, and Campbell (2017), as noted by Miller, Hald, and Kidd, provided criticism of the empirical literature used in the aforementioned meta-analysis.

“Kohut, Fisher, and Campbell (2017) have however heavily criticized much of the empirical literature used in this meta-analysis for its harm-focused orientation and assumption of direction of causality (see also Campbell & Kohut, 2017). Accordingly, these authors conducted their own qualitative investigation into pornography’s impact on men’s and women’s relationships. They found that participants reported positive effects much more frequently than negative effects. Interestingly, the most commonly reported negative effect was that pornography created unrealistic expectations of sex, in relation to what is expected of both females (e.g., willingness to engage in, and enjoyment of, certain sexual practices) and males (e.g., muscularity, penis size, erection quality, sexual stamina).”

While the majority of individuals tend to report positive effects from pornography consumption, it is important to acknowledge that there are some individuals who report negative effects. However, it is worth noting that certain variables can help explain why some people experience negative effects.

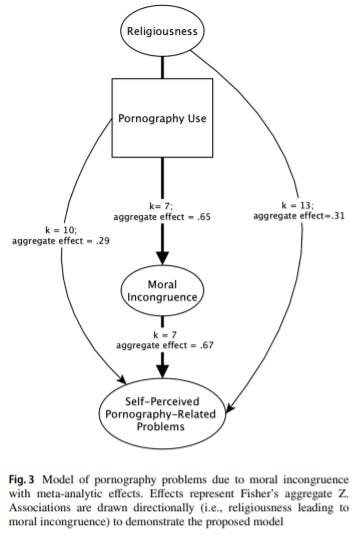

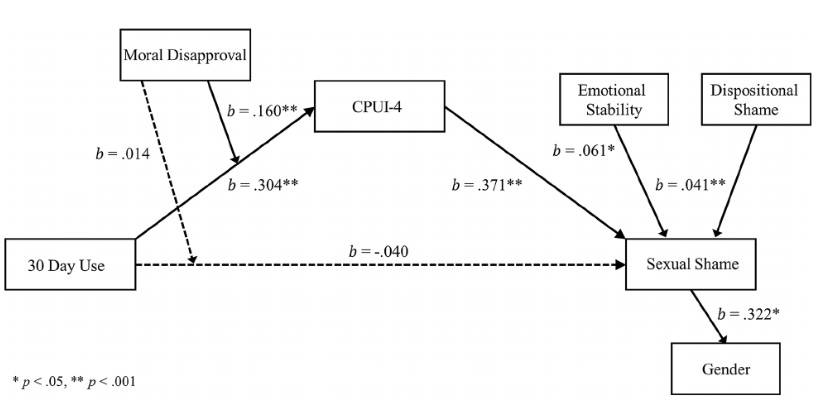

One such variable is moral incongruence towards pornography, which refers to having moral conflicts or issues with pornography despite engaging in its consumption. This concept is further elaborated in the subsequent mental health section, but in summary, individuals who hold moral objections to pornography but still engage with it may experience psychological distress. Therefore, it is plausible to suggest that self-reported negative effects can, to some extent, be attributed to moral incongruence.

Indeed, religiosity is another important variable that can contribute to the self-perceived negative effects of pornography. In a study by Stulhofer et al. (2021) involving a national probability-based sample of 4,177 individuals in Germany, it was observed that participants who reported negative effects of pornography were more likely to have a religious upbringing. This finding suggests a significant relationship between an individual's religious background and their perception of negative effects associated with pornography use.

When considering the factors of moral incongruence and religious upbringing, it becomes evident that self-reported negative effects may not solely stem from the inherent nature of pornography itself, but rather from moral concerns and religious beliefs regarding pornography. Individuals who hold strong religious beliefs and have been raised in environments that emphasize the potential harms or immorality of pornography may be more inclined to perceive negative effects when engaging with it.

The variable of dominance, particularly associated with traditional masculine ideology, can play a role in self-reported negative effects related to pornography consumption. Borgogna et al. (2019) conducted a study in which higher scores on dominance, as measured by the Traditional Masculinity Ideology (TMI) scale, were found to be associated with higher functional problems in relation to pornography use. Functional problems encompassed various areas such as personal relationships, social situations, work, and other important aspects of life.

One plausible explanation for the association between behaviors associated with traditional masculinity and functional problems could be a perceived incongruence between pornography consumption and one's own view of masculinity. Engaging with pornography might conflict with an individual's personal ideals or beliefs regarding masculinity, leading to potential psychological distress or moral concerns with pornography. Therefore, there may be an interaction effect between moral issues surrounding pornography and the influence of traditional masculinity, contributing to the self-reported negative effects experienced by individuals.

The aforementioned studies provide evidence suggesting that pornography consumption is generally associated with positive effects, such as increased sexual knowledge, attitudes, skills, relationships, and overall life satisfaction for the majority of individuals. However, it is important to acknowledge that there are individuals who report negative effects, and these experiences can be influenced by factors like moral incongruence and adherence to traditional masculinity norms.

2.2: Children

Concerns regarding the exposure of children to pornography are treated with great seriousness, often employing terminology associated with detrimental consequences when discussing instances where children are exposed to or may encounter sexual content. Within the context of child development theories, Benedek and Brown (1999) frequently employ the term "harm" when describing the effects of pornographic exposure on children. Similarly, Baxter (2014), in an article published by the American Bar Association, aligns with Benedek and Brown, contending that children's exposure to pornography is detrimental as it normalizes sexual harm, fosters aggression towards women, promotes negative attitudes and behaviors towards women, hampers affectionate relationships, and can lead to addiction. Echoing these arguments, Quadara, El-Murr, and Latham (2017) assert that pornography detrimentally affects children and young people across various domains, including mental health, sexual behaviors, and practices. These authors draw upon similar arguments as Baxter.

Flood (2009), when discussing his own research, highlights that his "review explores the harms among children and young people associated with pornography exposure." This underscores the prevailing perspective among commentators, who perceive pornography not as a helpful or neutral variable but rather as a negative one, engendering solely adverse effects. It is important to note that the effects attributed to pornography primarily stem from studies conducted on adolescents rather than children. However, commentators tend to generalize these findings to children, despite the differences in age groups. The ensuing section will delve into the negative effects posited by these commentators, with a particular focus on sexual development in children and adolescents.

The commentators consistently emphasize the concern that exposure to sexually explicit material may impart distorted perceptions of real sexual experiences, leading to the consensus that children, in general, should not be exposed to such material. This notion is encapsulated in the concept of sexual script theory. Horner (2020) explicates this theory, stating that pornography can introduce new sexual scripts to users (acquisition), reinforce existing scripts (activation), and through its portrayal of sexual behaviors as normal, appropriate, and rewarding, encourage the adoption of these scripts in both thought and behavior (application).

Supporting this perspective, Sun et al. (2016) discovered that frequent pornography consumption among men serves as a guide for their sexual behavior. Furthermore, Martellozzo et al. (2017), in a study conducted with a representative sample from the United Kingdom, found that 44% of boys reported that pornography influenced their perceptions of the types of sexual encounters they desired.

These findings underscore the influence of pornography in shaping individuals' sexual scripts and highlight the potential impact on young people's understanding and expectations of real-world sexual encounters. It is within this context that commentators express apprehension regarding children's exposure to pornography, as it may contribute to a distorted understanding of healthy and consensual sexual relationships.

Contrary to the negative perspective on pornography's influence on sexual behavior, it is important to consider that individuals may utilize pornography as a source of sex education rather than solely viewing it as having detrimental effects. In a systematic review exploring the use of pornography for sexual learning, Litsou et al. (2020) identified a prevalent theme across the included studies: the utilization of pornography as a form of sexual education.

The studies reviewed consistently highlighted that individuals turned to pornography due to a lack of comprehensive sexual education and limited access to sexual information from other sources. Pornography served as a medium through which individuals sought to learn about various aspects of sexuality, including sexual performance, roles, and positions. However, it is worth noting that participants in these studies also expressed certain limitations associated with pornography. They recognized that pornography often focused on specific kinks and fetishes, leading to insufficient coverage of diverse sexual experiences and information. As a result, unrealistic expectations could arise from exposure to pornography, further underscoring the need for improved and comprehensive sex education.

These findings suggest that individuals may turn to pornography as an alternative means of acquiring sexual knowledge in the absence of proper sexual education. Rather than solely attributing negative effects to pornography, it is crucial to acknowledge the complex role it plays in fulfilling informational gaps while recognizing the importance of comprehensive and inclusive sexual education to address these limitations.

It is important to critically examine the assumption that learning about sex from pornography is inherently negative, as critics of pornography often fail to provide a clear rationale for why this form of sexual learning is deemed problematic. Instead, their arguments often stem from the presumption that certain types of adolescent sexual behavior are inherently undesirable. The act of watching pornography and incorporating elements observed therein into one's own sexual experiences is often portrayed as inherently wrong solely because it originates from pornography, rather than being viewed as a positive exploration of personal preferences and boundaries within consensual relationships.

If commentators aim to mitigate the potential negative effects of pornography on sexual scripts, they should advocate for comprehensive sex education and the promotion of pornography literacy. Although still in the early stages of research, pornography literacy programs have shown promising results. For instance, in a study involving a small sample of 24 youths aged 15 to 24, implementing a pretest-posttest design, Rothman et al. (2018) found that providing individuals with education on pornography, healthy relationships, and the unrealistic sexual scripts depicted in pornography led to a shift in their perception of pornography as unrealistic and an inadequate source of sexual knowledge.

These findings highlight the potential benefits of incorporating pornography literacy programs into sex education initiatives. By imparting critical thinking skills and knowledge about the limitations and distortions often present in pornography, individuals can develop a more nuanced understanding of its influence on their own sexual scripts. Promoting comprehensive sex education and incorporating discussions on pornography can empower individuals to navigate their own sexual experiences with a more informed and critical perspective, fostering healthier attitudes toward sex and relationships.

The exposure of individuals to sexual education through pornography does not inherently imply negative attributes about pornography itself. Instead, it highlights the necessity for enhanced sex education and the development of pornography literacy. If critics of pornography intend to assist individuals in navigating the potential influence of pornography on their sexual scripts, it is imperative that they also advocate for improved sex education and the cultivation of pornography literacy. These educational approaches can serve as effective means to mitigate the effects of pornography on the sexual scripts of young individuals.

By promoting comprehensive sex education and integrating discussions on pornography, individuals can acquire the knowledge and critical thinking skills needed to navigate the complexities associated with sexual content, including pornography. Comprehensive sex education offers a foundation for understanding healthy relationships, consent, sexual diversity, and effective communication. Furthermore, incorporating pornography literacy into educational initiatives empowers individuals to develop a discerning perspective regarding the limitations, potential risks, and unrealistic portrayals commonly found in pornography.

When examining the sexual development of children, it appears that critics of pornography tend to perceive children through the lens of the "romantic child" model, which is commonly depicted in children's literature. This model portrays children as inherently pure, untainted by sin, and free from corruption by the external world. Consequently, according to this perspective, children should not be exposed to pornography since they are not yet at an appropriate age to learn about sex. However, this idealized view of childhood does not align with the reality of children's sexual development.

As discussed by McKee (2010), toddlers and preschool-aged children often exhibit behaviors related to self-exploration and engage in sexual activities with their peers. Between the ages of 2 and 6, children may engage in activities such as playing doctor, touching their own genitals, and displaying curiosity about the human body in its natural state. These observations indicate that children already possess an inherent interest in sexual development, challenging the assumption that they are completely unaware of sexual acts.

While the intention behind anti-pornography campaigns aimed at protecting children is commendable, it is important to acknowledge that assuming children are oblivious to sexual matters—beyond the oft-repeated "think of the children" sentiment—is based on a false premise. If children already have an inherent curiosity and interest in sexual development, the act of watching pornography, in and of itself, does not necessarily lead to negative sexual development.

Indeed, it is crucial to consider the age at which individuals are first exposed to pornography and its potential association with negative effects. According to the reasoning of anti-pornography critics, one would expect individuals exposed to pornography at a young age to report more negative effects, and age could be a relevant variable in explaining a significant portion of the variability in self-reported effects resulting from early exposure to pornography.

By examining the relationship between age at first exposure to pornography and the reported effects, researchers can gain insights into potential associations and shed light on the impact of early exposure. This approach allows for a more nuanced understanding of the potential consequences of early exposure to pornography on individuals' well-being and attitudes toward sexuality.

To begin, it is important to challenge the assumption that individuals who were exposed to pornography at a young age attached significant importance or meaning to it. As highlighted by McKee (2007), interviews conducted with individuals who encountered pornography before reaching puberty often described their experiences as lacking in significance and instead found them amusing. According to McKee, these interviewees, as pre-pubescent children, generally had little interest in pornography and found it to be a source of amusement.

McKee further notes that other factors discussed by the interviewees had a greater impact than pornography itself, including exposure to television and influences from religious education, such as Sunday school. This suggests that the potential harm associated with pornography may be overshadowed by other contextual factors that play a more substantial role in shaping individuals' experiences.

Additionally, the research by Litsou et al. supports the understanding that individuals who were exposed to pornography at a young age recognized its unrealistic nature. However, they did not view this recognition as inherently harmful, contrary to the arguments put forth by critics. These findings are consistent with the study conducted by Lebedikova et al. (2022), which revealed that exposure to pornographic content elicited neutral reactions among the majority of the participants in their sample.

Taken together, there is no compelling reason to assume that individuals who were exposed to pornography at a young age necessarily ascribed significant significance or negative effects to it. The interviews conducted by McKee indicate that pre-pubescent children generally had little interest in pornography and found it amusing. Moreover, the studies by Litsou et al. and Lebedikova et al. highlight that exposure to pornography, even among children, often evoked neutral reactions. These insights challenge the assumption that early exposure to pornography inherently leads to harmful consequences and emphasize the importance of considering individual experiences and contextual factors in understanding the impact of pornography on young individuals.

When examining the relationship between age at first exposure to pornography and self-reported negative effects, research indicates that age explains only a small portion of the variance. Mulya and Hald (2014) found that age at first exposure accounted for approximately 1.96% of the variance in self-reported negative effects stemming from pornography. Similarly, Miller, Hald, and Kidd did not find a significant relationship between age at first exposure and negative effects in their correlation matrix. Furthermore, in a multivariate regression analysis, an increase in age was associated with a slight decrease in negative effects, with the standardized beta coefficient indicating that age accounted for approximately 4% of the variance. These findings suggest that while age at first exposure may contribute to the understanding of self-reported negative effects, it explains only a small proportion of the overall variability.

The evidence presented suggests that age at first exposure to pornography may not be a substantial or highly influential variable when it comes to the perceived negative effects of pornography. This is supported by findings indicating that exposure to pornography before puberty may not be taken seriously by individuals and instead viewed as meaningless or amusing.

Given this understanding, it is possible that the variance explained by age at first exposure is overestimated, potentially masking its true coefficient. Furthermore, considering the inherent correlations between variables, it becomes questionable whether age at first exposure should be controlled for, especially in light of the findings from McKee's research.

Regardless, if critics of pornography are genuinely concerned about the well-being of children, it is recommended that they support initiatives such as pornography literacy classes and comprehensive sex education. These measures would represent a step forward for critics, as historically, even in the 1967 commission, there was hesitation to support sex education programs despite acknowledging the potential harm of pornography.

While it is commonly assumed by some anti-pornography critics that the average consumption of pornography occurs during the tween years, it is important to examine the available data to gain a clearer understanding of the actual ages of pornography consumption. Contrary to this assumption, the data often present conflicting information regarding the ages at which individuals engage with pornography. McKee (2020) and FTND (Fight the New Drug 2021) may suggest that pornography consumption occurs predominantly during the tween years, but it is crucial to critically evaluate the evidence supporting this claim.

The research findings provide valuable insights into the age of first exposure to pornography among males and females. According to Sabina, Wolak, and Finkelhor (2008), the majority of males (22.9%) reported their first exposure to pornography at the age of 15, while 33.0% of females reported it to be at 16. The data also indicates that a significant proportion of males (80%) reported first exposure at the age of 13 and above, compared to 90.9% of females. Exposure to pornography prior to the age of 13 was relatively uncommon, with the average age of first exposure for both males and females being 14. Furthermore, Lim et al. (2017) found that among individuals who had ever viewed pornography, 77% of females reported watching it at the age of 14 or older, whereas only 32% of males reported the same. On the other hand, 24% of females reported viewing pornography at 13 years of age or younger, in contrast to 69% of males. Additional data from Lewczuk, Wojcik, and Gola (2019) revealed that 25.99% of individuals between the ages of 7 and 12 had watched pornography, while the percentage increased to 32.0% for individuals aged 13 to 17. The remaining percentage accounted for individuals aged 18 and above. Sanz-Barbero et al. (2023) found the average age for males to be 14 and for females at 17.

These findings collectively shed light on the age distribution of first exposure to pornography, indicating that the majority of individuals experience it during adolescence, not childhood. Of course, a possible retort is that adolescents are still children — but there are fundamental differences between children and adolescents that do not allow for interchangeability in the words used.

Childhood typically refers to the period of human development from infancy to the onset of adolescence. It is a time of rapid growth and development, marked by significant physical and cognitive changes. During childhood, individuals undergo milestones such as learning to walk, talk, and develop basic cognitive skills. Children are typically dependent on adults for care, guidance, and protection. Their experiences are largely centered around family, play, and early educational environments. Childhood is characterized by a sense of curiosity, imagination, and a gradual acquisition of foundational knowledge and skills.

In contrast, adolescence is a transitional period that bridges childhood and adulthood. It is a time of profound physical, cognitive, and socio-emotional changes. Adolescence generally begins with the onset of puberty, which triggers rapid physical growth, the development of secondary sexual characteristics, and hormonal changes. This period is marked by increased independence, self-identity exploration, and a shift in social relationships. Adolescents strive for autonomy, seek peer acceptance, and grapple with questions of self-identity, values, and future aspirations. They undergo significant cognitive development, including the ability to think abstractly, engage in critical thinking, and consider multiple perspectives. Adolescence is a time of heightened emotional intensity and an increased capacity for forming intimate relationships.

In summary, childhood and adolescence represent distinct stages of human development. Childhood encompasses the early years of life, characterized by rapid growth, learning, and reliance on caregivers. Adolescence, on the other hand, denotes the transitional period between childhood and adulthood, marked by significant physical, cognitive, and socio-emotional changes as individuals navigate toward greater independence and self-identity (see Bronski 2021 for more). Recognizing and understanding these differences allows for tailored approaches to providing appropriate support, education, and interventions that align with the specific needs of children and adolescents.

For the sake of argument, let us assume that the average age when someone first watches pornography is at tween years. What can explain this? As was noted Ghorayshi (2022), puberty is beginning to start earlier. This is important as puberty predicts watching pornography among adolescents, according to Pirrone et al. (2020).

Hence, it is important to acknowledge that children possess an awareness of sexuality and engage in sexual activities. Furthermore, the onset of puberty has been found to be a significant predictor of pornography viewing, and some individuals do turn to pornography as a source of sex education. If critics genuinely wish to discourage children and young people from relying on pornography to learn about sex, it is imperative that they advocate for the implementation of sex education programs (Black 2022a; b) or support the introduction of pornography literacy classes. These initiatives aim to provide comprehensive and accurate information on sexual health, relationships, consent, and the potential implications of pornography. By offering robust sex education and promoting pornography literacy, critics can help equip children and young people with the knowledge and critical thinking skills necessary to navigate their sexual development in a healthy and informed manner, thereby reducing the reliance on pornography as a form of sex education.

Critics of pornography may argue that individuals who consume pornography may rationalize or justify their behavior, leading to a higher likelihood of reporting positive effects. This raises concerns about potential bias in self-reporting. Therefore, it is crucial to employ diverse methodologies and approaches to analyze the effects of pornography on various aspects, including relationships and mental health. By using different research methods and examining multiple dimensions, we can obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of pornography, reducing the potential influence of self-justification biases.

By conducting research across different domains and utilizing a range of measurement tools, researchers can gain a more nuanced and balanced perspective on the effects of pornography on individuals. This approach helps to address concerns regarding potential biases in self-reporting and allows for a more robust analysis of the complex dynamics involved in the relationship between pornography and various aspects of individuals' lives.

Relationship Effects

In contemporary society, the widespread availability and accessibility of pornography have sparked significant discussions and debates regarding its potential effects on individuals and their relationships. As the consumption of pornography continues to increase, it is crucial to understand the implications it may have on various aspects of intimate relationships. This chapter delves into the complex interplay between pornography and relationship outcomes, specifically focusing on its potential to hinder individuals from engaging in real sexual encounters, impede the formation of meaningful relationships or marriages, and influence dynamics within established relationships.

One key concern regarding pornography's impact on relationship outcomes is its potential to affect individuals' ability to transition from virtual sexual experiences to real-life sexual encounters. Engaging with explicit sexual content on screen may create a distorted perception of sexual intimacy, leading to unrealistic expectations and inhibitions when it comes to engaging in actual sexual activities. This chapter explores the existing research examining the possible hindrances that pornography consumption may pose in individuals' pursuit of real sexual experiences.

Furthermore, the influence of pornography on relationship formation and marriage is a subject of significant interest. It is essential to investigate whether pornography consumption affects individuals' attitudes, values, and behaviors related to establishing long-term partnerships. The chapter critically examines studies that explore the potential impact of pornography on relationship initiation, commitment, and the decision to enter into marriage. By analyzing the available evidence, we gain insights into how pornography may shape individuals' perceptions and choices regarding intimate relationships.

Moreover, the chapter delves into the effects of pornography within established relationships. It explores the potential consequences of one or both partners engaging in pornography consumption on relationship satisfaction, intimacy, trust, communication, and overall relationship functioning. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for comprehending how pornography may influence the dynamics between partners and the overall health of their relationship.

In addressing these issues, this chapter emphasizes the need for a nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the effects of pornography on relationship outcomes. By examining empirical studies from diverse perspectives and methodologies, we aim to provide a balanced assessment of the potential positive and negative consequences of pornography consumption on individuals' ability to engage in real sexual encounters, form meaningful relationships or marriages, and navigate the complexities within their existing relationships.

Ultimately, the goal of this chapter is to contribute to a deeper understanding of the impact of pornography on relationship outcomes, shedding light on the potential challenges and opportunities it presents for individuals seeking fulfilling and healthy intimate connections. By exploring the existing body of research, we hope to foster informed discussions and guide future investigations in this important area of study.

3.2: The Impact of Pornography on Real Sexual Encounters

According to Williams (2016) in The Independent, individuals associated with the NoFap movement argue that the prevalence of pornography among millennials has contributed to a decline in their sexual activity. These individuals claim that exposure to pornography has had a detrimental impact on their mental state, leading to a diminished desire for genuine sexual intimacy. Fradd further supports this notion by likening pornography to a synthetic and highly concentrated pheromone, suggesting that prolonged exposure to pornography can result in confusion or disinterest in engaging in real sexual encounters.

The apparent inhibition of individuals' inclination towards real sex due to the influence of pornography provides a compelling rationale for advocating against its consumption. Albright (2008) conducted a study that revealed a positive correlation between engaging in online sexual activities, such as erotic chatting, viewing pornography, interacting sexually with someone on the web, or seeking offline sexual encounters, and reduced arousal towards real sex for both males (r = 0.362) and females (r = 0.104).

Notably, it is important to acknowledge that a higher percentage of individuals reported increased sexual activity, as indicated by 14% of males and 17% of females.

In a study conducted by Sun et al. (2013) focusing on Korean men with a higher interest in extreme or degrading pornography (N = 470), a correlation was observed between this interest and a preference for pornography as a means to attain and sustain sexual excitement over engaging with a real partner (β = 0.18, p < 0.10). However, it is worth highlighting that factors such as older age (β = 0.20, p < 0.01) and relationship status (β = 0.24, p < 0.001) exhibited stronger predictive value in determining the preference for pornography over a genuine partner.

These findings suggest that while an inclination towards extreme or degrading pornography may be associated with a preference for pornography in achieving sexual arousal, other factors such as age and relationship status play a more significant role in determining individuals' choice between pornography and engaging in real sexual relationships.

While the aforementioned studies contribute to the discussion, it is important to critically examine the findings and consider the limitations of the research. The Albright study, for instance, reported weak-small correlations between seeking sex online and reduced arousal by real sex. These effect sizes indicate a relatively modest relationship and should be interpreted with caution.

Additionally, the Sun et al. study raises concerns regarding the use of an alpha level of 0.10 in their analysis. This choice of significance threshold may lead to increased risk of false positives or Type I errors, thereby casting doubt on the reliability and robustness of the reported associations.

To further investigate the potential impact of pornography on individuals' engagement in real sexual relationships, a viable approach would involve examining the relationship between pornography consumption and the number of sexual partners. By assessing individuals' pornography use patterns alongside their sexual behaviors, a more direct exploration of the potential influence of pornography on partner selection and engagement in real sex can be conducted. This approach would provide valuable insights into the association between pornography consumption and individuals' actual sexual experiences.

When considering the relationship between pornography consumption and sexual behavior, it is important to establish the default hypothesis as a starting point for discussion. The default hypothesis posits that individuals who engage in pornography consumption are more likely to experience heightened sexual arousal, and this arousal is expected to increase with greater consumption of pornography. Under the default hypothesis, it is assumed that individuals who consume pornography have a strong inclination and desire to engage in sexual activities with others.

However, it is crucial to emphasize that the default hypothesis does not assert a direct causal relationship between pornography consumption and sexual desire and the number of sexual partners. Rather, it suggests that individuals who are more frequently sexually aroused are more likely to consume pornography and also engage in sexual activities with others. It is important to distinguish this perspective from the alternative hypothesis put forth by critics of pornography, who may imply a causal link between pornography consumption and reduced sexual desire or fewer sexual partners.

Nevertheless, there is empirical evidence that supports the default hypothesis.

Pfause and Prause (2015a) conducted a study involving 288 men to explore the relationship between pornography consumption and the desire for sex with a partner. The findings of this study revealed that individuals who consumed higher amounts of pornography exhibited a stronger desire to engage in sexual activities with a partner. This supports the notion put forth by the default hypothesis that increased pornography consumption is associated with heightened sexual desire in the context of partner-based sexual encounters. Additionally, it is worth noting that Pfause and Prause (2015b) provided a response to Wilson's site, further contributing to the scholarly discourse on this topic.

In a study conducted by Bennet et al. (2019), the relationship between pornography consumption, sexual desire for one's partner, and relationship satisfaction was examined. The findings of this study indicated that pornography consumption did not have a negative impact on sexual desire for one's partner. Rather, the level of trait affection was found to be positively associated with greater sexual desire for one's partner. Furthermore, sexual desire was identified as a significant predictor of relationship satisfaction. Interestingly, the study also revealed that feelings of guilt associated with pornography consumption negatively influenced sexual desire for one's partner. These findings provide evidence that challenges the alternative hypothesis by suggesting that pornography consumption is not directly associated with lower sexual desire for one's partner, but rather guilt related to pornography use may have a negative impact on sexual desire within the context of a relationship.

In a study conducted by Willoughby et al. (2013), the association between pornography use and the number of sexual partners was examined, taking into account gender differences. The findings revealed that among men, higher levels of pornography use were associated with a greater number of casual sexual partners. However, this association was not observed among women. Instead, for women, moderate levels of pornography use were found to be associated with a higher number of sexual partners.

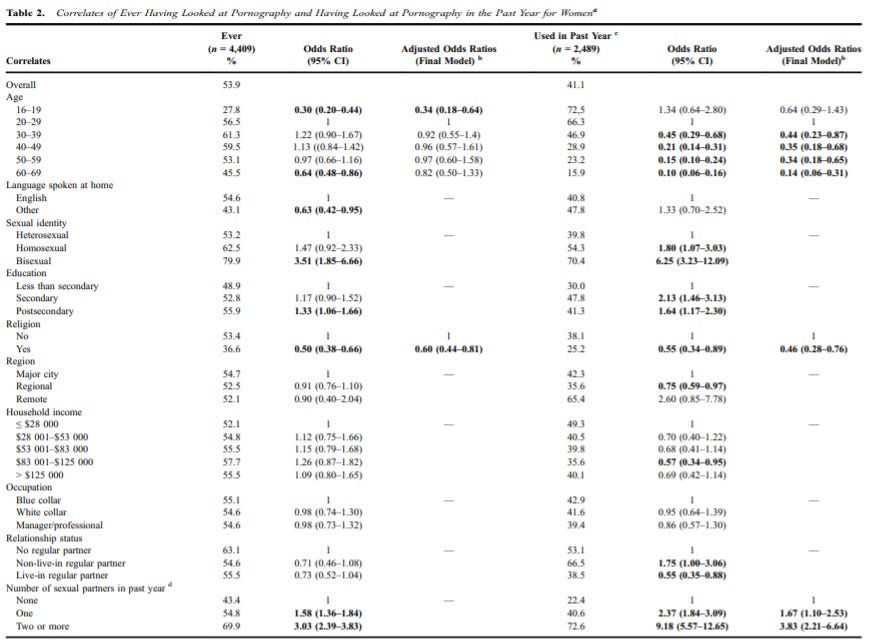

According to Rissel et al. (2016), the association between pornography use and the number of sexual partners was investigated among men and women. The findings revealed that individuals who reported watching pornography in the past year were more likely to have had multiple sexual partners in the same time frame. Specifically, both men and women who reported watching pornography in the past year had higher odds of having two or more sexual partners compared to those who did not watch pornography, with odds ratios of 3.58 for men and 3.83 for women.

Furthermore, the study found that there was an association between overall pornography use and the likelihood of having a single sexual partner. Both men and women who reported watching pornography overall had higher odds of having one sexual partner compared to those who did not watch pornography, with odds ratios of 1.31 for men and 1.67 for women.

In a study conducted by Komlenac and Hochleitner (2022), the relationship between pornography use and partnered sex was investigated among a sample of 644 medical students. The findings indicated that there was a positive association between pornography use and the frequency of engaging in partnered sexual activity for both men and women.

Among male participants, a significant positive association was observed between pornography use and the frequency of partnered sex, with a beta coefficient of 2.83. This suggests that as pornography use increases, men tend to engage in sexual activity with a partner more frequently.

Similarly, among female participants, there was a significant positive association between pornography use and the frequency of partnered sex, with a beta coefficient of 1.98. This indicates that women who reported higher levels of pornography use were more likely to engage in sexual activity with a partner more frequently.

In Braun-Courville and Rojas (2008), the impact of exposure to sexually explicit websites on sexual behavior among adolescents aged 12-22 was investigated. The study included a sample of 492 participants, and the findings revealed significant associations between exposure to sexually explicit websites and the number of sexual partners.

Specifically, adolescents who reported exposure to sexually explicit websites were found to have a higher likelihood of having more than one sexual partner in the last three months, with an odds ratio of 1.8. This suggests that adolescents who were exposed to sexually explicit websites were more likely to engage in sexual activity with multiple partners within a relatively short period. Furthermore, the study also found a significant association between exposure to sexually explicit websites and the number of lifetime sexual partners. Adolescents who reported exposure to such websites were more likely to have had multiple sexual partners throughout their lifetime, with an odds ratio of 1.8.

In Häggström-Nordin, Hanson, and Tydén (2005), the relationship between pornography consumption and sexual behavior among 718 students from 47 high school classes in Sweden was examined.

The findings of the study indicated that high pornography consumption was indeed associated with an increased likelihood of having sexual intercourse with a friend. Specifically, the odds ratio (OR) for engaging in intercourse with a friend among individuals with high pornography consumption was 1.75. This suggests that students who reported consuming pornography at a high frequency were more likely to engage in sexual activity with a friend compared to those with lower levels of pornography consumption.

Braithwaite, Coulson, and Keddington (2015) conducted a study to investigate the relationship between pornography consumption and engaging in friends-with-benefits relationships, as well as the number of unique friends-with-benefits partners. The study aimed to examine whether an increase in pornography consumption was associated with a higher incidence of friends-with-benefits relationships and a greater number of unique partners in such relationships.

The findings of the study revealed a positive association between pornography consumption and both the likelihood of having friends with benefits and the number of unique friends with benefits partners. Specifically, individuals who reported higher levels of pornography consumption were more likely to engage in friends-with-benefits relationships and had a greater number of unique partners in such relationships compared to those who reported lower levels of pornography consumption.

Wright, Bae, and Funk (2013) found a positive association between pornography consumption and the number of sexual partners among women. Specifically, women who reported consuming pornography had a greater number of sexual partners in both the prior year and the prior 5 years compared to women who did not consume pornography.

These results are similar to the ones found in Wright (2013), but this one focused on males rather than women.

The data presented from various studies shed light on the relationship between pornography consumption and sexual encounters. Overall, the findings suggest that higher pornography use is associated with certain patterns in sexual behavior, although the effects may differ based on gender and other factors. It is important to note that these findings align with the default hypothesis, which posits that individuals who consume pornography are more likely to be sexually aroused and have a stronger desire for sexual activity.

The accumulation of research findings on pornography consumption and sexual encounters provides support for the default hypothesis rather than the alternative hypothesis. The default hypothesis suggests that individuals who consume pornography are more likely to experience heightened sexual arousal and have a stronger desire for sexual activity. The data discussed, including studies by various researchers, consistently indicate that higher pornography use is associated with an increased number of sexual partners and engagement in certain sexual behaviors. These findings align with the notion that individuals who are more sexually aroused are inclined to consume pornography and subsequently engage in sexual encounters. In contrast, the alternative hypothesis, which implies a negative impact of pornography on sexual desire and engagement, is not strongly supported by the available evidence.

3.3: Processing into Relationships & Marriages

Among some of the more reactionary arguments, it’s said that pornography stops its consumers from forming relationships with other people. Fradd hints at this assumption, saying,

Which activity sounds more “mature” and grown-up: making love for a lifetime to one real flesh-and-blood woman whom you are eagerly serving and cherishing, despite all her faults and blemishes (and despite your own), or sneaking away at night to troll the Internet, flipping from image to image, from one thirty-second teaser to another, for hours on end, pleasuring yourself as you bond to pixels on a screen?

Zillman and Bryant (1988) exposed students and non-students to either a pornography film or an R-rated film for 6 consecutive weeks. After the end of the 6-week, it was found that individuals exposed to pornography had a lower view of marriage being an essential institution. Unfortunately, Zillman and Bryant do not offer the standard deviations in each group to calculate Cohen’s d to estimate the magnitude of the difference, an issue given the inability of p-values to tell us if an effect truly does exist or not (see Wasserstein, Schirm, and Lazar 2019 for more).

Questions #26-#29 were used to examine the effects continued exposure to pornography had on one’s views on marriage as an institution. Those who were part of the experimental group saw a decrease in their support for question #26 (38.8%), no significant results for question #27, an increase of 36.2% for question #28, and regulation from the government was viewed as less needed.

Although pornography may lead to a lower view of marriage being important as an institution for society, this does not translate to being less likely to be married or a lower desire to be married. Individuals may not consider marriage an important institution, but this does not mean they would not like to be married.

In another study, Malcolm and Naufal (2014) find that pornography consumption is consistently negatively associated with the probability of being married.

While the study can not show causation given its cross-sectional nature, it clearly indicates a negative coefficient in all the different models used. However, an issue with Malcolm and Nafual’s analyses is that pornography consumers are assumed to be equal across class; in other words, those who watch low amounts are the same as those who watch moderate and high amounts of pornography.

Both Zillman and Bryant and Malcolm and Nafual’s work rely on assumptions that are not borne out by the literature. First, Zillman and Bryant assume that attitudes toward marriage are predictive of behavior. Zillman and Bryant’s assumption assumes that consumers will think less of marriage, and thus be less likely to be married. Second, Malcolm and Nafual assume pornography consumers are a monolithic group, with no differences between those who differ in the amount of pornography they watch. The former assumes that views are predictive of behavior, and the latter assumes no group differences. This is not the case.

Perry's (2020) analysis of the 2012 New Family Structure Study (NFS) and the Relationships in American Survey (RAS) indicates a positive association between pornography consumption and the desire to be married. The study found that individuals who reported higher levels of pornography use were more likely to express a desire for marriage. These findings suggest that the notion of pornography diminishing individuals' interest in marriage may not hold true and that other factors may contribute to individuals' attitudes and desires regarding marriage.

If Zillman and Bryant’s findings were consistent in predicting actual behavior, we should not expect individuals who watch pornography at a higher rate to have a higher desire to be married, to begin with. The Zillman and Bryant findings should, theoretically, predict a lower desire to be married. This does not align with Fradd’s argument that pornography consumption would lead to the “belief that marriage is sexually confining” if consumers have the desire to be married. Why would those who view marriage as “sexually confining” have a desire to be married?

Fradd, Zillman, and Bryant might object to this response, possibly arguing that desire may not translate to actually becoming married. Indeed, it’s possible for an individual to desire marriage, but this does not mean they will actually become married. In the case of pornography and getting into marriage, the relationship is nuanced.

According to Perry and Longest (2019), their findings suggest that heavy pornography consumption decreases the chances of marriage for men but not for women. Interestingly, both abstinent individuals and those who watch pornography at a high frequency exhibited lower chances of getting married. This indicates that there may be distinct differences between individuals who consume pornography moderately, those who consume it heavily, and those who abstain entirely.

Again, assuming Bryant and Zillman’s findings were accurate predictors of behaviors, we should not expect pornography consumers to even transition into marriage. It’s possible that there may exist interaction effects between individuals who watch high amounts of pornography and those who watch no pornography at all and their personalities. In other words, personality differences might lower the odds of getting married and might decrease their chances of being a good partner. Personality differences between groups of pornography consumers are noted more in-depth in Chapter 5. To conjoin the chapters quickly, it’s found that individuals who watch high levels of pornography report more mental health issues than individuals with low-frequency use, and these mental health issues might lower the odds of getting married. However, it’s important to note that pornography consumption is not associated with these mental health issues in a causal or linear way.

However, not everyone wants to be married, to begin with. So, it’s possible that pornography consumers are less likely to be in general relationships than in marriage. Herbenick et al. (2020) found a high OR for women between pornography consumption and being in another relationship, meaning not single or in a relationship, but just something else, but a low OR for everything else but “other.” This suggests that women with more niche sexual desires in the target-sexual behaviors may simply be in something else besides a standard relationship.

For men, there was a high OR across the board and no relationship between pornography consumption and being single.

3.4: Effects on Relationship Outcomes

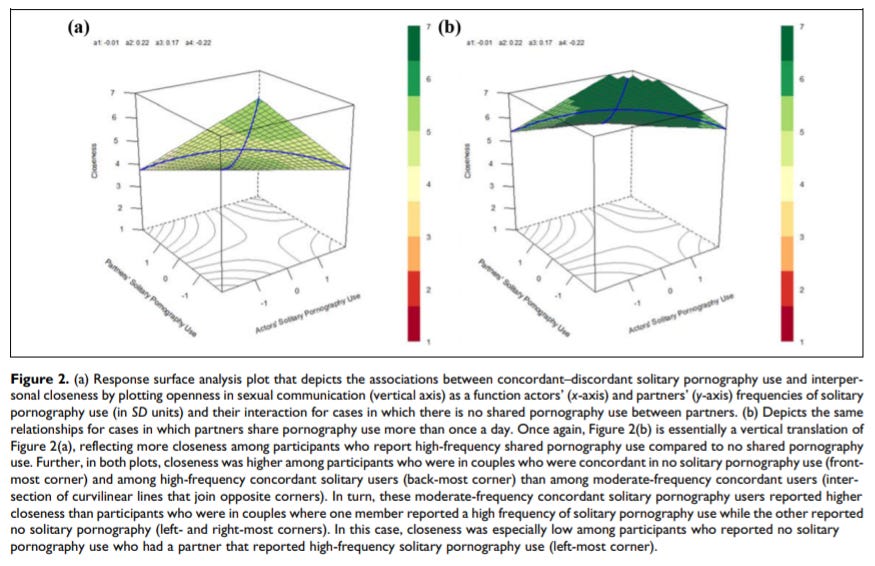

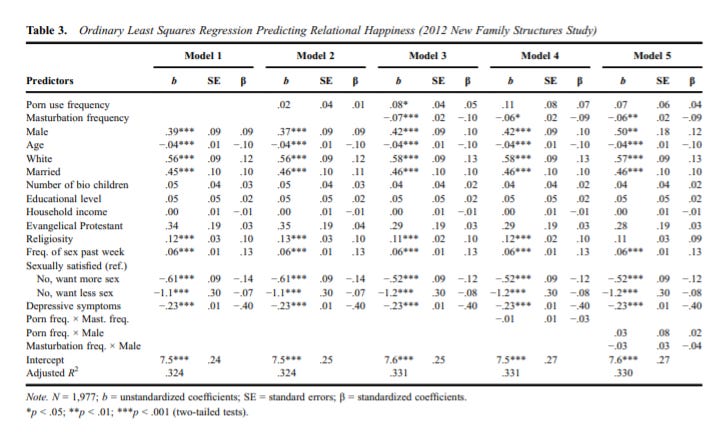

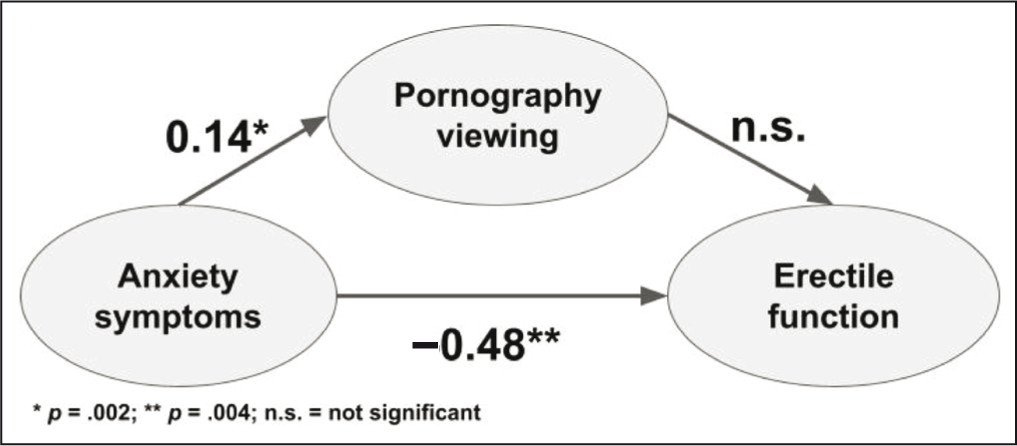

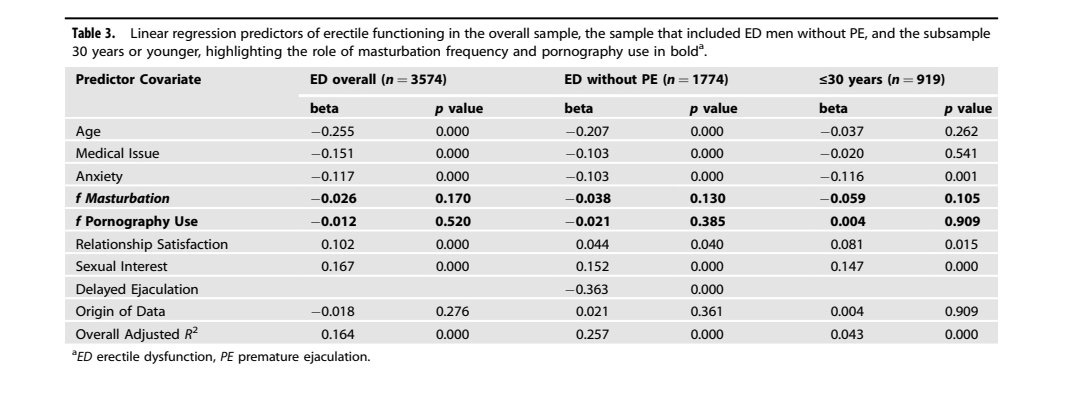

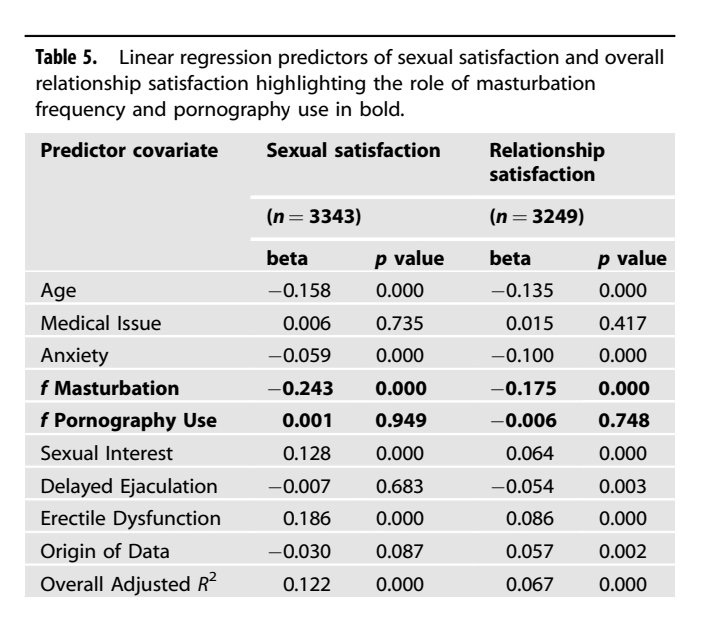

Since pornography does not stop one from having sex or finding a real partner, we should expect pornography to possibly have effects on relationship outcomes, even if they do not hinder one from forming relationships, to begin with. The prevailing perspective, particularly espoused by critics of pornography, posits a negative association between pornography consumption and various relationship outcomes. The Christian Broadcasting Network states that watching pornography can lead to domestic violence, increase the divorce rate, fosters insecurity, creates worthlessness, and can decrease sexual satisfaction with one’s partner (Gibbons 2018). Fradd (2017: 105) remarks that, based on his acquired evidence from the literature, pornography affects “…our ability to form and to maintain meaningful relationships.” These views align with how other critics of pornography discuss the issue (e.g., Paul 2006; Wilson 2015; Foubert 2016). One of the most popular slogans that claim pornography is harmful to relationships comes from Fight the New Drug, specifically their saying that “Porn kills love” (Fight the New Drug 2022). These discussions by critics have shaped public perception, leading many to believe that pornography poses a threat to their own relationships.