Dazed but Probably Not So Confused: Debunking Some Myths About Marijuana

Marijuana is not a gateway drug, is not causally associated with lower mental health, does not cause psychosis for most people, doesn't lower IQ, does not cause delinquency, does not affect the brain.

Within the cannabis community, 4/20 is considered an important day and slang term since it refers to smoking cannabis, typically at 4:20 p.m., and because it’s a day to celebrate cannabis around the world. The background of 4/20 is interesting and goes to show how far trivial things can become culturally important to some. However, we aren’t here to talk about the history of cannabis culture and instead discuss the effects of cannabis on various aspects of society and individuals. In this article, I will argue that cannabis is not harmful to things like mental health, IQ, memory, etc. For ease, I will leave a table of contents for easy navigation so one can CLTR + F the section they want instead of scrolling till you see what you want.

7 myths about marijuana debunked. Nothing else to say. As my friend said during a concert, "light up that blunt, Ozzy" (updated 1/21/23)

I. Marijuana Is Not a Gateway Drug

II. Marijuana & Mental Health

III. Marijuana And Psychosis

IV. Marijuana Doesn’t Lower IQ

V. Marijuana and Delinquency

VI. Marijuana and the Brain

VII. Marijuana Addiction

There are other myths surrounding marijuana that would be interesting to analyze, but that’s something that’ll already make a lengthy article even longer.

Anyways, let’s get started. Also, an honorary picture from the film Dazed and Confused.

I. Cannabis as a Gateway Drug

The issue of cannabis being a “gateway” drug is one that has purveyed in anti-drug culture since Reefer Madness. Indeed, the fears of cannabis use being a steppingstone into harder drug use has continued to be argued in mainstream media. During a TV interview, Senator Marco Rubio (R) claimed that,

"When you decriminalize something, the message that you're basically sending people is it must not be that bad," Rubio said. "Now, suddenly, you're an 18- or 17-year-old, [and you] say, 'Well, I know marijuana, you tell me not to smoke it, but you know what? It can't be that bad, because the federal government made it legal.' And so all of a sudden now, you're going to have a problem in this country, because that becomes a gateway. We know that marijuana use is often the first thing that people use before they move on to something else. We've also seen, by the way, marijuana being purchased off the streets that's laced with fentanyl and other drugs, and it's killing people."

Robert DuPont, president of the Institute for Behavior and Health and the first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, argued in The New York Times that “Marijuana is a gateway drug” (Levintan 2015, see DuPont 2016 for more). Evidence for an association comes from the fact that drug users have reported using marijuana first, and then moving onto hard drugs. As DeSimone (1998) puts it,

This premise arises from evidence that the overwhelming majority of adolescent and young adult cocaine users have previously used marijuana [O'Donnell and Clayton, 1982; Mills and Noyes, 1984; Yamaguchi and Kandel, 1984; Newcomb and Bentler, 1986; Kandel and Yamaguchi, 1993] and is known as the gateway hypothesis

Tullis et al. (2008) argue that among their sample of university students, “students who initiated smoking behavior with marijuana are significantly more likely to smoke tobacco in the same hour than students who initiated smoking with tobacco are to smoke marijuana in the same hour.” Thus, “marijuana smoking might be a gateway to cigarette smoking.” Akin to this, Merril, Lewis, and Pulver (1994) also argue that marijuana is one of three gateway drugs because users of hard drugs have done marijuana before moving onto hard drugs.

Tandy (2005), writing in Police Chief, says that cannabis “may become a ‘gateway’ drug for more dangerous drugs.” Similar complaints are echoed in other areas of literature, like in Clayton and Leukefeld (1992) & McAlister (1987).

The 1999 report from the Institute of Medicine, however, provides a broader view pertaining to the gateway hypothesis (IOM 1999). They define the gateway hypothesis as two meanings: (1) The properties of marijuana itself might lead others to trying hard drugs, and (2) Marijuana serves as an entrance into the world of drugs that lead others to trying other drugs. As examples, (1) means that Joe might like the effects of marijuana and thus might try hard drugs that give similar effects, and (2) Joe might buy marijuana from someone and see that they sell other drugs, too, thus increase the chances of him trying other drugs. IOM states that “The latter interpretation is most often used in the scientific literature, and it is supported, although not proven, by the available data” and that “Instead, the legal status of marijuana makes it a gateway drug.”

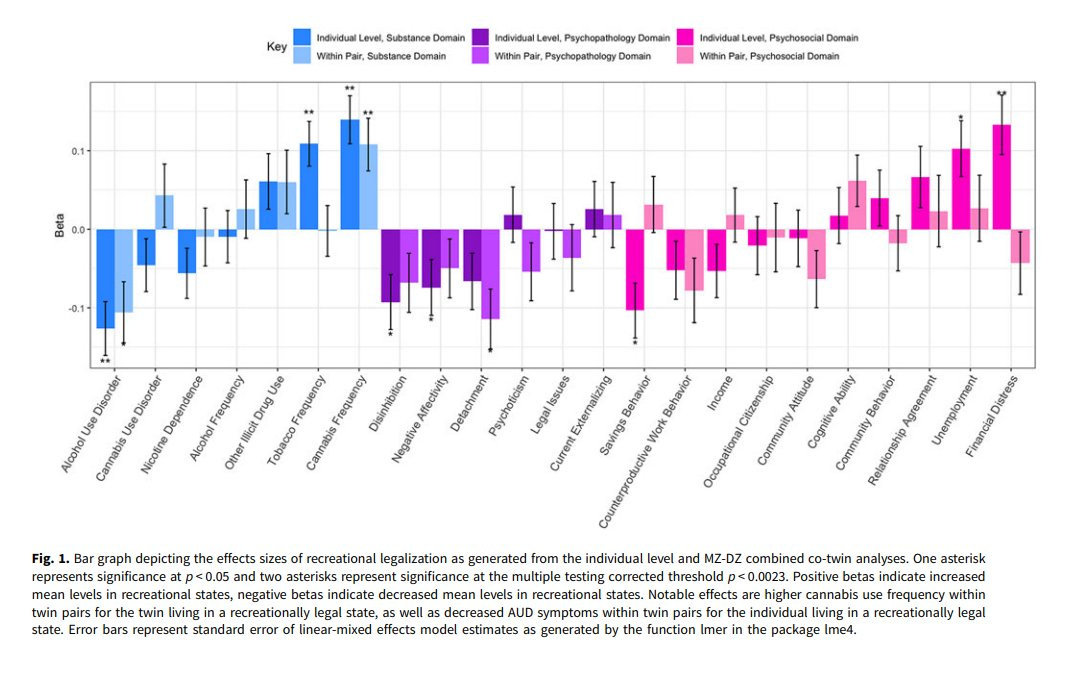

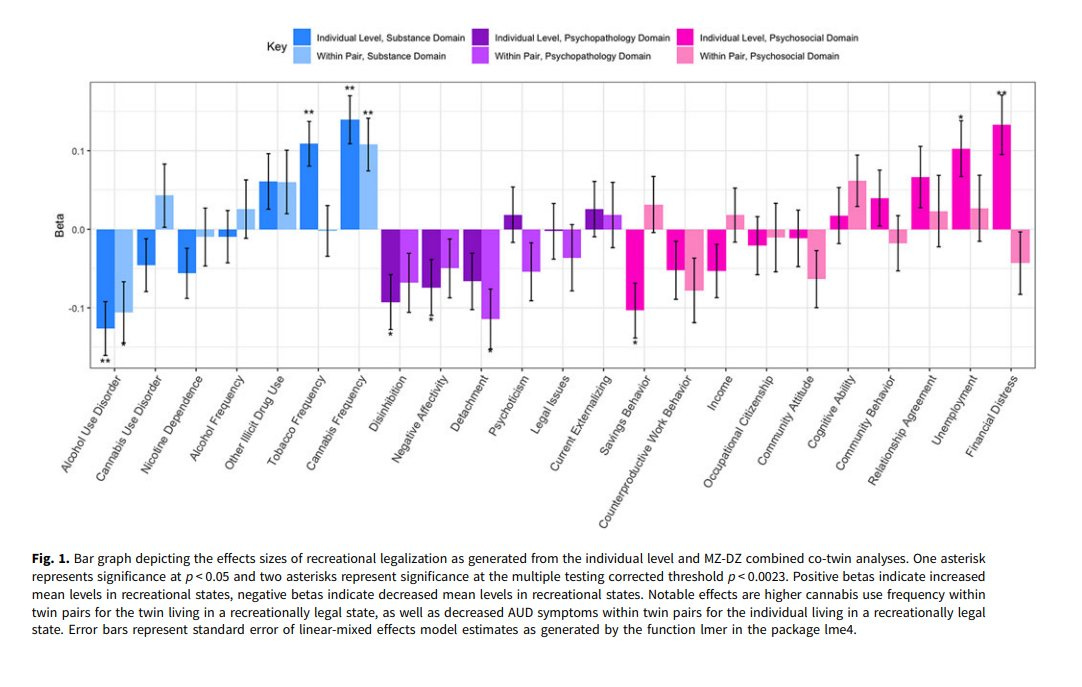

Using a co-twin design that looks at twins living in areas with recreational cannabis and those with strict laws on recreational cannabis, Zeller (2023) tested to see if the legalization of cannabis would lead to increases or decreases in social and economic outcomes.

Based on their data — which is the within-pair boxes that we care — Zeller et al. found no evidence that the legalization of cannabis led to increases in nicotine dependence, alcohol frequency, tobacco frequency, and other illicit drug use.

If cannabis was a gateway drug, either through meaning (1) or (2), then the twin living in an area that allows recreational cannabis should go onto other illicit drug use, and we should see the effects in the bar graph. Instead, we see no such things, casting doubt on the gateway hypothesis being true.

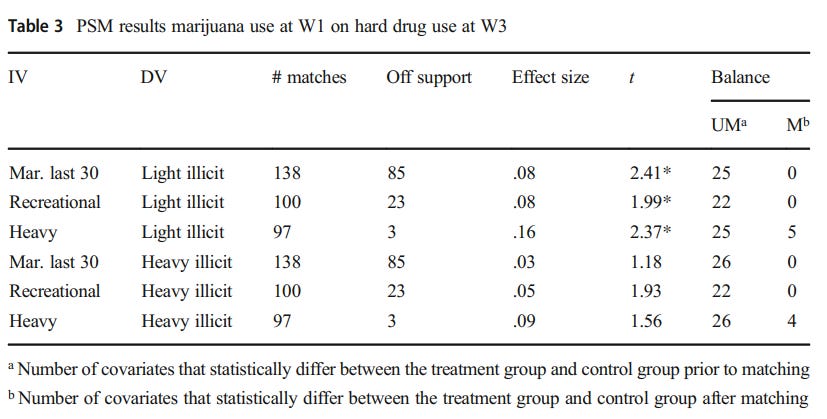

Of course, while it is true that cannabis use does tend to precede other illicit drug use, this does not necessarily imply a causal relationship. Jorgensen and Wells (2021) examined data from 2002-2006 that came from the NLSY, a nationally representative sample that has been used for a respectable number of years now. The researchers used propensity score matching (PSM) to create a group that is like the experimental group in distinctive characteristics. Looking at the effects of marijuana use in wave 1 on hard drug use in wave 2, there was no relationship between marijuana use in wave 1 and hard drug use in wave 2, showing no support for the idea that marijuana is a gateway drug.

Focusing on marijuana use in wave 1 and hard drug use in wave 3, the researchers found that light illicit drug use in wave 3 was predicted by marijuana use in wave 1 (t = 2.41, p < 0.05), recreational marijuana use (t = 2.41, p < 0.05), and heavy marijuana use (t = 2.37, p < 0.05). However, sensitivity analyses showed that these effects were caused by an unobserved covariate. Once further tests were done, these effects became insignificant, except for the relationship between heavy marijuana use in wave 1 and light illicit drug use in wave 3, with the effect size being 0.16 — indicating a weak gateway effect that was “substantively meaningful.” This effect, though, came from the least conservative model and was sensitive to hidden bias, according to the authors.

When looking at the effects of marijuana use in wave 2 on hard drug use in wave 3, heavy marijuana use in wave 2 was associated with an increase in light and illicit drug use in wave 3. These effect sizes were weak, came from the least conservative model, and were sensitive to hidden bias.

Considering all 18 tests together, there was no support for the idea that marijuana is a gateway drug. 12/18 tests found no support for the idea that cannabis is a gateway drug, 3 tests found effect sizes less than 0.10, 3 tests found weak effects in support of the idea that marijuana is a gateway drug (effect sizes ranged between 0.11 to 0.17). The 3 tests that showed an effect came from poor models and were sensitive to hidden bias. After controlling for common liability factors, there was no causal relationship between marijuana and trying hard drugs.

The co-twin design offers the strongest piece of evidence against the gateway hypothesis. If cannabis was a gateway drug, it should have led to increases in other drug use, but this was not the case. However, further evidence casts doubt on the gateway hypothesis being true.

Sabia et al. (2021) used data from the National Survey of Drug Use and Health which measures drug use among respondents.

Vanyukov (2021) criticizes the gateway hypothesis because of its use of using a drug once as a measurement rather than progression. If one person were to use cannabis and then try LSD once, for example, it would be counted as a reference point in favor of the gateway hypothesis.

In a literature review by the National Institute of Justice (2017), the researchers found that one 2016 study found that progression from one substance to other substances was due to personality traits and environmental factors rather than the substance first used. An earlier study found that “the association between using cannabis and using other illicit drugs becomes insignificant after accounting for stress and various sociodemographic factors, such as age, education, employment, and family status.” However, they note that the evidence is inconclusive.

The Benjamin Center (2017) said that “There is compelling and enduring evidence that marijuana is not a gateway drug.” Rather, the use of cannabis and other illicit drug use might come from a common factor that leads one to trying both cannabis and other drugs rather than a causal relationship. An example might be going to school and buying books at the bookstore; it might not be that going to school causally leads to going to the bookstore and buying books, but rather some common factor that leads to both going to school and buying books.

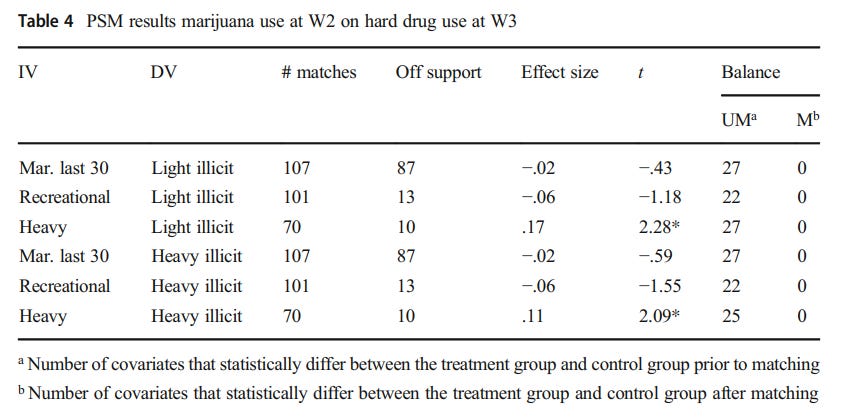

Morral, McCaffrey, and Paddock (2002) used a common-factor model that makes use of drug use propensity, drug use opportunities, drug use initiation, and marijuana use frequency. Data came from the National Household Survey of Drug Abuse. They find that “While not disproving the existence of a marijuana gateway effect, our findings demonstrate that the primary evidence supporting gateway effects is equally consistent with an alternative model of adolescent drug use initiation in which use, per se, of marijuana has no effect on the later use of hard drugs.” Once drug use propensity is adjusted, the differences in hard drug use between users and non-users goes away. In other words, users of any drugs simply have a higher propensity to use other drugs than non-users.

Discussing past studies which have continued to find that marijuana use was a predictor of illicit drug use, even after variables like background characteristics were adjusted for, the authors note that these studies assume a strong correlation between drug use propensity indicators and true drug use.

As shown above, the drug use propensity indicator must have a strong correlation with true drug use before the relationship between cannabis use and hard drug use can be eliminated. As the authors say, “it is hardly surprising that controlling for these covariates does not eliminate the association between marijuana and hard drug use.” Thus, marijuana itself does not lead to trying other drugs, akin to the co-twin design — but rather is a result of a shared common factor that leads to trying marijuana and doing other drugs, too. For example, a common risk factor also exists between early onset cannabis use and later nicotine dependence (Agrawal 2008).

There are other issues with the gateway argument. Despite the gateway argument not being based on a causal model, most consumers of other illicit drugs tried alcohol or tobacco first, not marijuana (Barry et al. 2016).

Second, in areas where cannabis use has been legalized, there have not been increases in other illicit drug use (see Sabia et al. above). After non-medical cannabis was legalized in Washington, alcohol, cigarette use, and pain reliever misuse decreased (Fleming et al. 2022).

The co-twin design above also offers evidence for this argument.

Because of the evidence laid above, I argue that the gateway hypothesis may be true, but not causal. In other words, simply consuming cannabis does not lead one to trying other drugs, and being exposed to a market that sales other drugs besides cannabis of may also not lead one to trying other illicit drugs. If this were the case, the co-twin design should have shown this. Rather, the relationship is due to a common variable between consuming cannabis and trying other drugs rather than a causal relationship between the two.

II. Marijuana & Mental Health

When discussing the effects of cannabis use on psychological well-being, it’s been argued that cannabis use is associated with lower mental health. The CDC says, “Marijuana use has also been linked to depression; social anxiety; and thoughts of suicide, suicide attempts, and suicide.” Lev-Ran et al. (2013) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on the issue, finding that

“The OR for cannabis users developing depression compared with controls was 1.17 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.05–1.30]. The OR for heavy cannabis users developing depression was 1.62 (95% CI 1.21–2.16), compared with non-users or light users.”

This argument has also made its way to online political discourse. For example, the Leftists commentator Hunter Avallone has argued that smoking cannabis leads to lower mental health (was on Twitch, do not have VOD), and it was even argued by the right-wing commentator Blake Kresses and on his and other’s podcast, The KGB Show.

That there is an association between cannabis use and lower mental health does not tell us if marijuana itself is responsible. An association between the two variables can exist, but this tells us nothing about causal effects. Much like the gateway drug assumption, marijuana use is not causally associated with lower mental health once further controls are adjusted for.

Fiengold et al. (2016) used data from the nationally representative sample from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Once prior mental disorders were adjusted for, cannabis use did not lead to an increase in anxiety disorders.

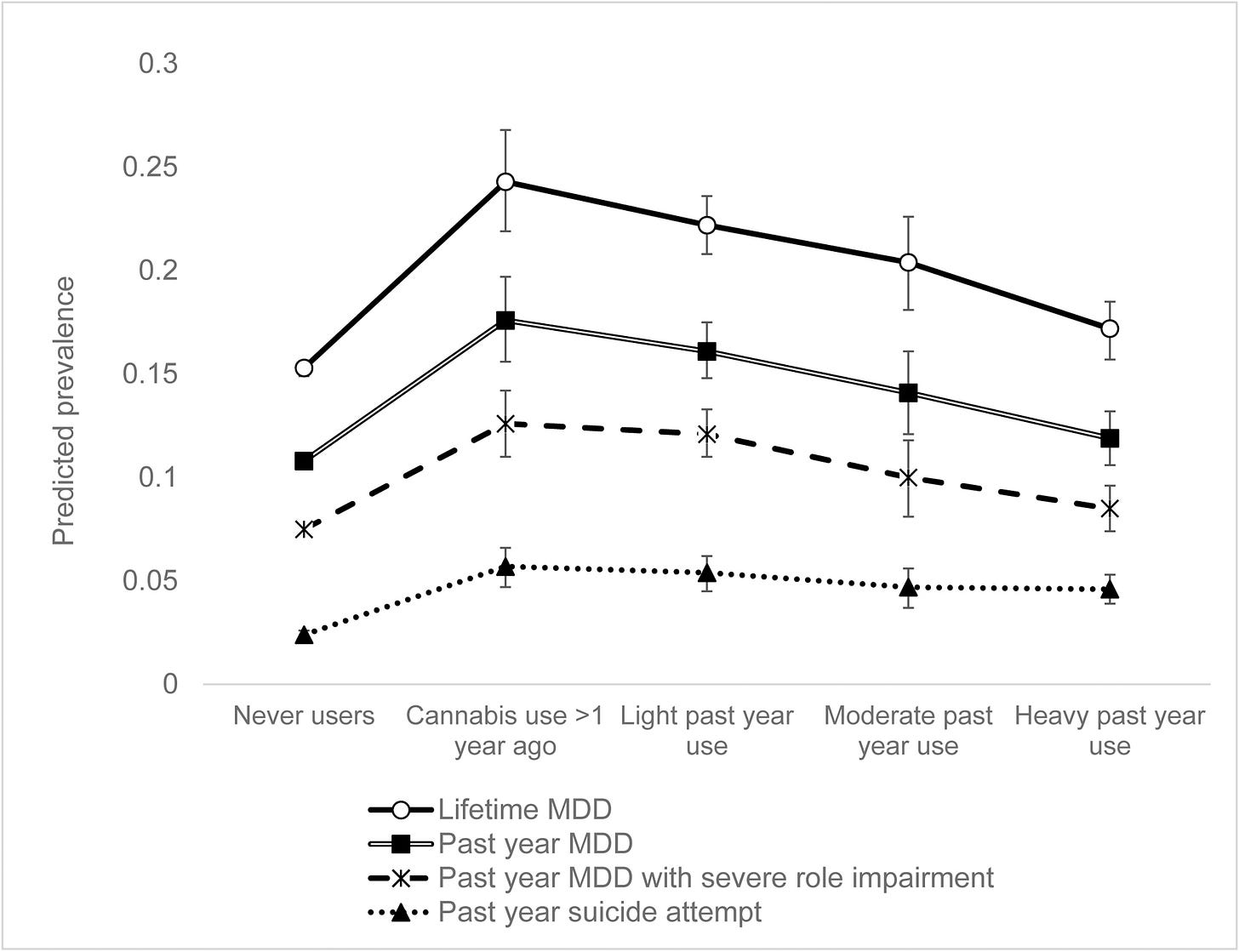

Gukasyan and Strain (2020) found that heavy use of marijuana was associated, not with higher major depressive disorders (MDD), but rather lower lifetime rates of major depressive disorders when compared to other users. When covariates were adjusted for, heavy cannabis use was not associated with significantly different odds of past-year major depressive disorders when compared to never users.

Light and moderate users had a higher risk of MDD, but as will be argued, this is most likely not a causal relationship.

Monshouwer et al. (2018) found that after adjusting for alcohol consumption, sociodemographic variables, social support, and family affluence, there was no significant relationship between marijuana use and lower mental health.

However, marijuana use was associated with delinquent and aggressive behavior, but this is an issue discussed in section V.

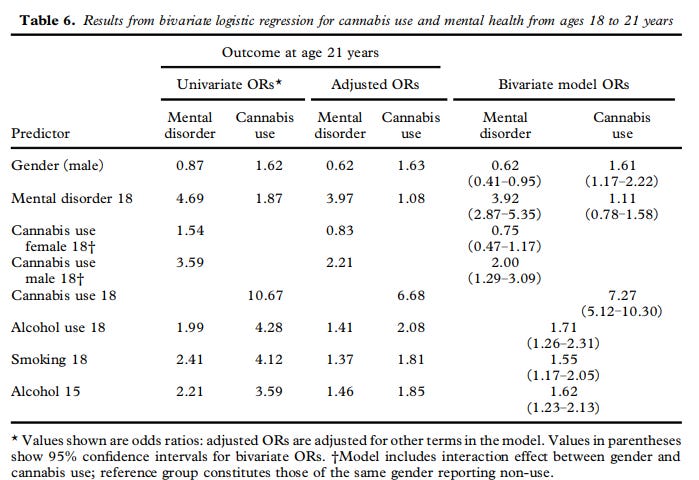

McGee et al.'s (2000) longitudinal study ranging from adolescence to adulthood found that “[T]here was no significant relationship between frequency of cannabis use at age 18 and diagnosis of internalizing disorder at age 21 years.”

While cannabis use was associated with mental health issues at a later age, this was not the fault of cannabis, but rather a symptom of pre-existing issues. “Cannabis use was not markedly associated with anxiety/depressive disorders, but rather was elevated among those with externalizing disorders suggesting that, by and large, cannabis use may not be functioning simply as ‘self-medication’ for anxious or depressed individuals.”

Green and Ritter (2000) found that after the use of other drugs was controlled, the relationship between cannabis use and depression went away.

De Graaf et al. (2010) adjusted for childhood conduct problems and this made the relationship between marijuana use and depression become insignificant. According to the authors,

“Based on data from the 13 countries that administered the childhood conduct problems assessment, and prior to statistical adjustment for this index of early norm violations, the aRR for the estimated cannabis-depression association was modest at 1.18 (95% CI: 1.02, 1.37; P ¼ 0.02). With statistical adjustment for the index of early norm violations, the estimated cannabis-depression association dropped towards the null value and lacked statistical significance (aRR ¼ 1.08, 95% CI: 0.93, 1.25; P ¼ 0.32).”

Harder et al. (2006) used data from the NLSY and found that after adjusting for other group differences, the odds ratio for self-reported depression and cannabis usage was statistically insignificant. Degenhardt et al. (2001) found no significant association between cannabis usage and anxiety and depression after controlling for risk factors such as neuroticism and the usage of other drugs.

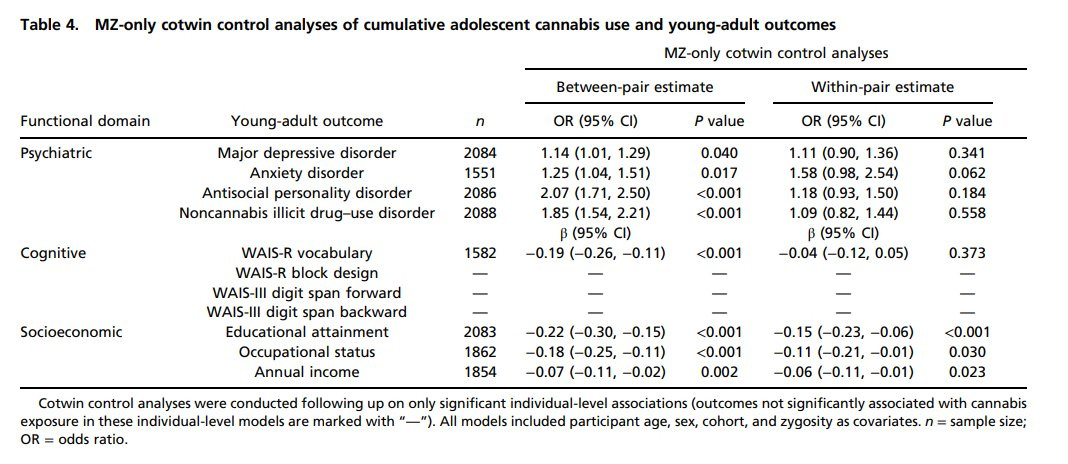

A co-twin design from Schaefer et al. (2021) found no causal relationship between marijuana use and lower psychological well-being and IQ.

They find a relationship between things like educational attainment and income, but the authors suggest this might be due to shared environments or genetic influences that might overlap.

It seems that cannabis use doesn’t lower mental health, but what could drive this relationship if not cannabis itself? As has been suggested in other works, individuals with traits associated with lower mental health might use cannabis as a form of self-treatment for their issues. Buckner et al. (2007) found that social anxiety disorder served as a major risk factor for using cannabis. Zimmerman and Morgan (1997) provided multiple lines of data showing psychological issues to come before marijuana use, not after, and that people with psychological issues turn to cannabis as a form of treatment for themselves.

III. Marijuana and Psychosis

This section is pretty short since it’s easy to shoot down. Yes, there is an association between cannabis use and psychosis, but this is not causal. Instead, it may be genetic and as a form of help rather than a cause.

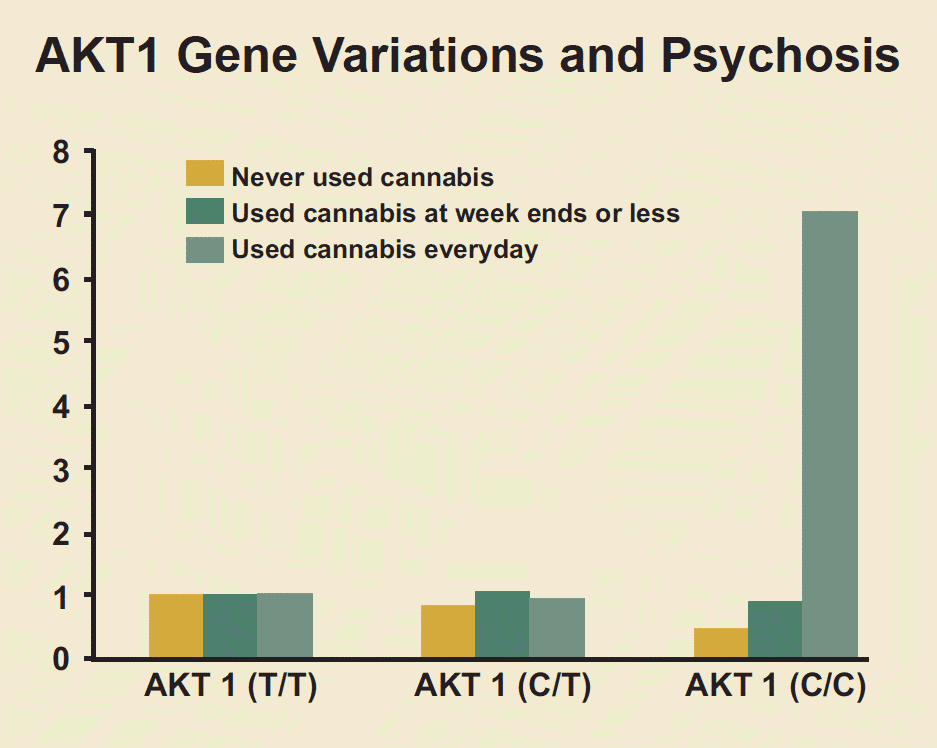

On the genetic side, individuals with genes associated with psychosis might trigger harsh reactions due to the ATK1 gene variant. People who smoke cannabis and who have the ATK1 gene have a higher risk of developing psychosis (Di Fort et al. 2012).

Because of this, individuals with genetic risks to psychosis should refrain from consuming cannabis.

Another co-twin study found that marijuana use was not causally associated with multiple negative outcomes, including traits associated with psychosis: “negative psychiatric outcomes, including major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, antisocial personality disorder, non-cannabis illicit drug use disorders, and psychoticism" were not associated with adolescent cannabis use (Schaefer et al. 2022). Schaefer et al. (2021) found no causal relationship between cannabis use and psychosis using a co-twin design, instead, it was due to familial confounders.

The same held true when looking at differences in exposure rate to cannabis by twins, and those who have cannabis use disorder.

The association between psychosis and cannabis might be driven by the fact that those with odd symptoms, things as psychosis, might go to cannabis as a form of help (Andreasson, Allebeck, and Rydberg 1989), and symptoms come before cannabis (Thornicroft 1990). This is important since those with psychosis and other issues prefer cannabis as their choice of drug (Dixon et al. 1991) and cannabis might exaggerate these issues, so people with psychosis should refrain from cannabis, if possible.

So, the relationship might not be there. Furthermore, a sniff test should show that increases in cannabis use should be followed by increases in psychosis. We do not see such an epidemic (Hall and Solowij 1998). More recently, Wang et al. (2022) found that in Colorado after cannabis legalization, there was no significant association between cannabis dispensaries & schizophrenia ED visits per capita, but there was an association w/ the rate of psychosis visits.

As we have already seen, the relationship between cannabis and psychosis is not causal, and there’s no reason to assume that the relationship between cannabis exposure and schizophrenia is causal, too. As Proal et al. (2014) finds, “having an increased familial risk for schizophrenia is the underlying basis for schizophrenia in these samples and not the cannabis use.”

Another co-twin design finds that legalizing cannabis did lead to an increase in cannabis use but was not associated with increases in alcohol use disorder, financial distress, alcohol quantity, and cannabis use disorder, other illicit drug use, negative affectivity, psychoticism, and other things (Zellers et al. 2023).

A general issue with this type of stuff is also the dose level one takes, as new cannabis smokers might take too much cannabis which leads to psychosis issues while high, but this tends to go away as the high wears off (source: me, took cannabis) and the way one takes cannabis is also important. An edible, if too strong, can certainly lead to psychosis-like symptoms while high but this is not permanent; and the same could happen if the person smokes too much cannabis. Again, these aren’t permanent, but users who try cannabis should start with low doses and slowly build their way up if they want to mediate these effects. However, marijuana doesn’t cause long-term psychosis.

IV. Marijuana Doesn’t Lower IQ

The character of the stupid stoner is one that has made its place in popular culture. From Slater in the film Dazed and Confused, anecdotal stories of people who swear marijuana made someone they know or barely know an idiot. It’s assumed that marijuana lowers intelligence among its users. I’m not sure about you, but Slater didn’t sound dumb when he was talking about Washington and marijuana when he said

“Behind every good man there is a woman, and that woman was Martha Washington man, and everyday George would come home, she would have a big fat bowl waiting for him, man when he come in the door, man she was a hip, hip, hip lady, man."

Jokes aside, the idea that marijuana causes declines in IQ is based on studies where non-users are compared to users and have their IQ measured and compared, but this is a crude way to examine the effects of marijuana on IQ as there are too many confounding genetic and environmental variables. Does marijuana lead to lower IQ? Do individuals with lower IQ just happen to smoke marijuana? These are questions that can be answered in twin studies where we can adjust for genetic and environmental variables, something that can’t be done in a proper way through the use of non-twin data.

Ross et al. (2019) studied data from twins and measured their IQ through Raven Progressive Matrices and the Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale III, and executive functions, like working memory, response inhibition, and mental shifting). As was expected, marijuana was not causally associated with declines in intelligence.

Between families, families with higher cannabis use did have lower IQs, but within families, those with higher cannabis use often did not have lower IQs. In the case where one twin used marijuana, both twins suffered from drops in IQ. This suggests that marijuana, then, does not decrease IQ in such a causal way as some people think it does.

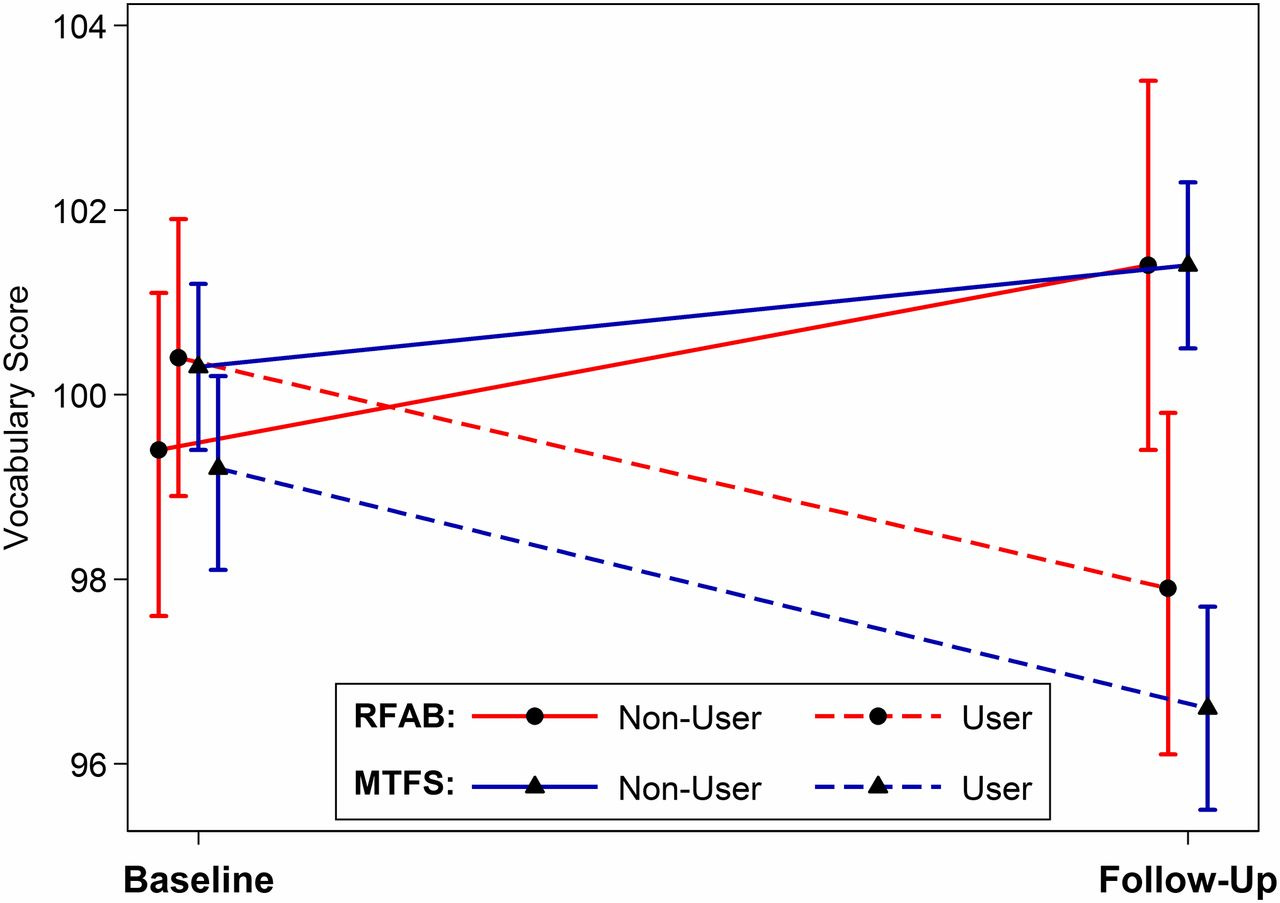

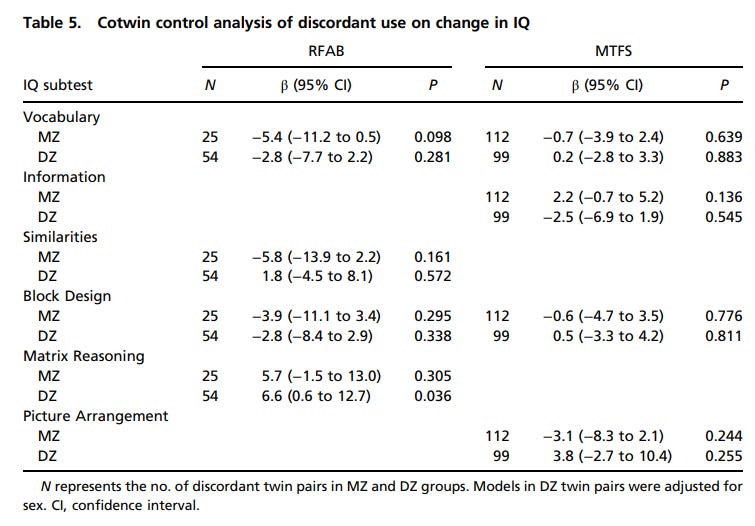

Jackson et al. (2012) had participants from two-population based samples of twins fromThe Risk Factors for Antisocial Behavior (RFAB) study and the Southern California and the Minnesota Twin Family Study (MTFS), and measured the twin’s intelligence through four subtests of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence for one sample and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Revised for another and their marijuana use. To determine whether the IQ change between marijuana users was the same across both samples, a bootstrapping method was used, and a cotwin control was used to estimate the effect of genetic and family environment on marijuana use and IQ through the use of discordant use among twins.

When it came to vocabulary scores, scores from baseline to follow-up were significantly different between both users and nonusers in both samples. Participants who used marijuana showed greater decreases in their vocabulary score, with this effect being significant even after adjustments for cohort effects and age, sex, race, SES, etc. Similar effects were found in the Information subtest. However, once adjustment for other substance use was done, there were no statistically significant differences in vocabulary scores for the MTFS sample.

Changes in block design were unrelated to marijuana use for both samples. There were no significant differences in the extent of change for Similarities and Matrix Reasoning in the RFAB sample and no significant differences in Picture Arrangement in the MTFS sample.

Focusing on whether the frequency of marijuana use and declines in IQ, marijuana use that was greater than 30 times, and daily use were not significantly associated with declines in marijuana use among users. This held even after abuse with other substances was adjusted for.

When comparing a non-using twin to their using twin, there were no significant differences in IQ changes for Vocabulary, Similarities, Information, Block Design, and Picture Arrangement. There was a significant difference in the RFAB sample for matrix reasoning which showed that marijuana-using twins showed greater increases in performance.

As the authors say, “At the baseline assessment—before marijuana involvement—future users already had significantly lower scores on these subtests than nonusers in the MTFS.” Therefore, low IQ comes before marijuana, not after. That low IQ comes before marijuana use was also found in another study making use of twin data.

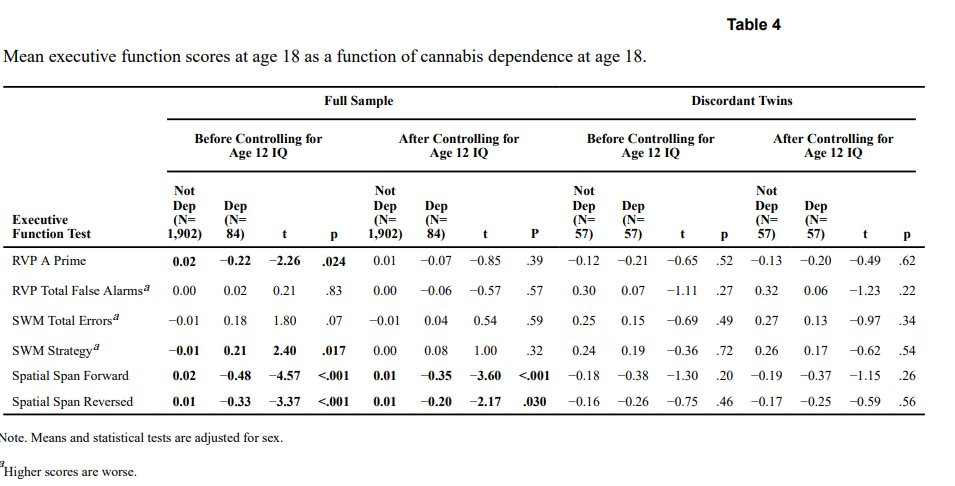

Meier et al. (2017) compared co-twins who differed in cannabis use; one twin was dependent on cannabis, and the other wasn’t. There was no causal relationship between cannabis use and declines in IQ when these twins were compared, and they performed the same on executive functions—except in one test of working memory where the difference was small.

Similar results were found in the Schaefer et al. study cited above, where they compared twins under a co-twin design. The non-causal relationship was also found when adjusting for differences in exposure rates to cannabis between twins.

That marijuana isn’t associated with IQ is also reflected in school grades, something that can be a proxy for intelligence, kinda. As was found in Earleywine (2005), among college users and non-users, there is no significant difference in grades or changes in their major, and 2 studies found higher grades among users. Among high schoolers, though, heavy users did show low grades, but these low grades were there before marijuana use began. As Earleywine said,

In addition, high school students who smoke cannabis heavily also tend to use alcohol and other illicit substances. Once these factors are taken into account, the link between cannabis and academic performance disappears. These results suggest that drugs other than marijuana might lower grades (Hall, Solowij, & Lennon, 1994).

Davis et al. (2022) found no relationship between cannabis use and non-high school completion once poly-drug use was adjusted.

Focusing on memory specifically, it’s been argued that marijuana messes with an individual’s ability to memorize stuff. Oftentimes, researchers give a sample of users exposed to marijuana a test of memory and see how they perform and find that, when compared to non-users, users score low on these tests. However, “memory” in the cognitive sense is overly broad, so what type of memory does it affect?

Remote memory, which is memory about the past, is unaffected by marijuana (Chait and Pierri 1992; Tart 1971). Focusing on recognition memory, the way to measure the effects of marijuana on recognition memory is to give someone a list of words, have them remember it, and then repeat it to the researchers. Although users perform poorly on these tests, it might be because users do not consider stuff like this important. Indeed, users can remember important life events (Yuille et al. 1998). This suggests that users can remember stuff they deem important, but not stuff they don’t deem important. Other studies have also found no difference in memory between users and non-users (Satz, Fletcher, and Sutker 1976). Overall, it does seem like marijuana might affect memory, but these issues are on stuff considered unimportant by the user and are temporary (Zimmer and Morgan).

Gitlow et al. claim that marijuana does cause lower IQ, among other issues discussed in this article, but many of their claims do not stand up to scrutiny and they seem to assume that correlation = causation. While this is a weird position to be taken up by the Florida Drug Policy Insitute, their claims simply do not stand up to scrutiny.

The character of the stupid stoner is one that’s played out in media and popular culture, and while true, this doesn’t seem to reflect marijuana harm itself. As was shown, not only do marijuana users do fine in higher education, but those that have low IQs already have low IQs independent of marijuana use itself.

V. Marijuana and Delinquency

As was found in section II, marijuana was associated with behavioral issues like aggression and delinquency, but as will be shown here, this is not the fault of marijuana itself. Rather, behavioral issues came before marijuana use, not after it.

As early as the 1970s, the 1972 Shafer Commission, a report that argued for the decriminalization of marijuana which was ignored by the government, found that, although users of marijuana showed aspects of delinquency, this was not because of marijuana itself.

“Some users commit crimes more frequently than non-users not because they use marijuana but because they happen to be the kinds of people who would be expected to have a higher crime rate, wholly apart from the use of marijuana. In most cases, the difference in crime rates between users and non-users is dependent not on marijuana use per se but other factors.”

Data on juvenile delinquents and adult offenders have found them to use marijuana at a higher rate than the general population, but this is not a causal relationship in which marijuana use leads to committing crimes. Once social environments, life histories, personality, and use of other drugs are controlled, the relationship between marijuana use and offending goes away (Fagan 1990; Ausubel 1958).

A large issue with studies showing a positive relationship between cannabis use and criminality is that researchers do not know if the user was high when committing crimes, instead, it’s just assuming that cannabis does lead to crime rather than testing to see if the user was high at the time of hostility which leads to criminality. Instead, users who do cannabis and who commit crimes might share some underlying personality traits associated with aggressive behavior (Sussman et al. 1999). When users of marijuana are also asked about the effects marijuana can have on aggressive behavior, they do not think marijuana causes them to become aggressive (Halikas, Goodwin, and Guze 1971).

Of course, asking others about how marijuana affects them might lead to social desirability bias. Lab experiments have shown that when injected with high doses of THC, participants are less likely to give someone else a strong shock, a measurement used as a proxy for violence since THC seems to have no impact (Myerscough & Taylor 1985).

Most criminals who consume cannabis began committing crimes began doing so before consuming cannabis (DuPont and Goldstien 1979). In an older review of the literature, Clayton notes that,

There is considerable consensus that involvement in delinquent behavior precedes any use of illicit drugs. This generalization clearly does not apply to alcohol use but does apply to the total range of illicit drugs investigated.... There is consistent, compelling evidence that delinquency precedes illicit drug use

So, criminality comes before drug use, not after. This is important since if marijuana was associated with delinquency, it would come after, not before.

Even focusing on longitudinal studies, we find no relationship between marijuana and criminality. Pederson and Skardhamar (2010) found that in their longitudinal sample, cannabis was not associated with non-drug offenses like violence but was associated with drug offenses. This reflects more on the issue of the criminalization of drugs, which is a discussion for another time, but shows that the relationship between marijuana and non-drug-related crimes is not significant.

Denson and Earleywine’s (2008) work found that there was no relationship between marijuana use and aggressive behavior in their study of 6,910 people once adjusting for alcohol use, history of hard drug use, gender, and age.

However, their study also found that deviant personality does not drive the relationship between marijuana use and aggressive behavior. Because of this, it’s possible that personality might not drive marijuana use nor might not lead to aggressive behavior. Marijuana, though, is unrelated to aggressive behavior. Another study, though, found personality to mediate the relationship between cannabis use and aggression (Tomlinson, Brown, and Hoaken 2003).

Osrowksy (2012) finds that the literature is mixed on if marijuana is associated with violent behavior and crime, but there are a few key parts to point off. As Orsowsky notes, alcohol use, race, high-risk groups, etc. An updated 2021 review found that marijuana also did not increase nor decrease crime at a state level.

Because of this, and the studies above finding crime to come before marijuana use, I am inclined to believe that the relationship between marijuana use and delinquency may be spurious. Bad people happen to smoke cannabis and happen to commit crimes, but cannabis itself might not be the cause of this. Furthermore, the legalization of marijuana has not led to an increase in crime or decrease, further casting doubt on marijuana leading to negative behaviors or criminality.

VI. Marijuana and the Brain

The idea that marijuana use can lead to diminished areas of one’s brain is one that seems popular with a simple Google search. It’s scary to think that marijuana can cause changes in brain structure, but this does not seem to be causal.

Knodt et al. (2022) found that cannabis users did have diminished areas of the brain compared to non-users. According to the authors, cannabis users had “a thinner cortex, smaller subcortical gray matter volumes, and higher machine learning–predicted brain age than nonusers.” However, one polysubstance use was adjusted, users do not have diminished areas of the brain when compared to non-users.

Not what we should expect given the scary headlines one can find.

In fact, the same holds true for adolescents who use cannabis. When adolescent cannabis users are compared to non-users, Lorenzetti et al. (2022) found that their meta-analysis finds no brain structural differences between users and non-users.

Furthermore, they note that “that the age of young cannabis users did not significantly predict group differences (SMDs) in the volumes of the ICV, TBV, TGM, TWM, hippocampus, amygdala, total, medial, and lateral OFC, and cerebellum. Further, there was no significant effect of cannabis use level (onset, duration, lifetime cones, and monthly cones) on SMD group differences for ICV, hippocampus, and amygdala, and of lifetime episodes on SMD group differences in ICV.”

The following section is more “controversial” since we are technically killing a sacred cow. In my opinion, after doing research on pornography addiction which required research on addiction science, I’ve come to the conclusion that addiction science is very poor for a large number of reasons. However, when it comes to drugs, there are findings I haven’t really seen cited by addiction centers or those who talk about addiction. When I say “addiction”, I really mean an inability to stop using drugs or whatever substance one is using. I do not think most substances are addictive in nature, rather individuals with pre-existing issues and genetic risk factors might be at risk for abusing drugs and these issues make it hard to quit, but these individuals do not represent most people. Thus, addiction in a sense seems like a scary kid’s story for most normal people, but those with issues might abuse drugs and this makes it seem like it’s addictive. You’ll understand what I mean.

VII. Marijuana Addiction

First off, something most people do not seem to know is that there is no agreed-upon definition of what “addiction” even is. As noted in Giugliano (2009), researchers operationalize the construct in different ways, causing confusion about what exactly addiction even is. Because of this, I will rely on the criteria used by the DSM which is dependence. Dependence requires 3/7 criteria for someone to be diagnosed with dependence, those being: (1) tolerance (needing more of behavior or stimulus to obtain or maintain the same effect; (2) withdrawal effects once the behavior or stimulus is not used anymore; (3) the behavior is engaged in for long durations of time than it was intended to be; (4) unsuccessful efforts to control or stop the addictive behavior; (5) significant time spent preparing for and recovering from addiction; (6) “important” activities given up or reduced due to addictive behaviors; (7) continuing to engage in said addictive behavior despite the negative consequences.

All these definitions share common similarities, which include repeating behaviors, behaviors that could be triggered by cues that are internal or external, and the behavior is irresistible to the user, even though there are consequences. However, while they share an overlap, they also have distinct differences that do not allow them to be used interchangeably. A further discussion on this will one day be held, but I’ll leave it here for now. Let’s continue on.

By using the criteria of the DSM, is cannabis addictive? Can users stop depending on drugs or other stimuli without seeking help, like going to a rehabilitation center or something of the like? Well, if you believe in addiction, then you would say that those who are dependent on something need a medical professional to help them, but this is not what we see in the real world. In the real world, most people can stop doing drugs, some even hard drugs, too.

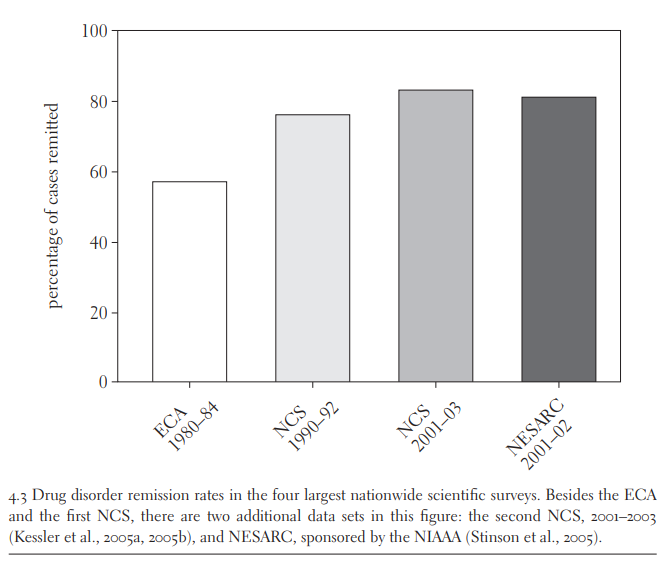

Heyman (2009) reviewed the remission rates of substance abuse from 4 studies: 1980-84 ECA, 1990-92 NCS, 2001-03 NCS, and the 2001-02 NESARC. The first study used the American Psychological Association’s revised criteria for who is considered an addict and made use of a nationally representative sample. The 2nd and 3rd studies also made use of a nationally representative sample but also used more liberal criteria for who was considered an addict, with only one symptom being required than three. The final study also made use of a nationally representative sample and made use of the DSM criteria for addiction.

For all the studies, there was a high rate of remission, with the NCS 2001-03 showing the highest rates of remission. Even though different criteria for addiction were used, they all showed similar results.

So, it seems that for most people “addiction” seems to not be something they face if they can simply stop using drugs that are deemed addictive in the first place. These findings also fit in line with other longitudinal studies showing high remission rates for the majority of people who fit the criteria for being addicted to drugs.

Teesson et al. (2015) focused on 615 heroin users and measured different variables at baseline, 3, 12, 24, and 36 months post-baseline, and again at 11 years post-baseline, with a final sample size of 431 people from the Australian Treatment Outcome Study (ATOS). The DSM-IV diagnosis was used to classify people who used heroin as being dependent on it or not. For both heroin use and heroin dependence, the majority of people stopped using heroin as time went on.

Considering it’s often said how addictive heroin is (e.g. Hosztafi 2011; Peri 2020), it’s interesting to see that most people can simply stop using heroin, including those who are considered to be dependent users.

Focusing on ATOS, Darke et al. (2015) found that both men and women remained in abstinence at pretty high rates at baseline and in the follow-up 11 years later, along with the waves in-between.

As was noted above, seems most people can stop using heroin, with the majority of people remaining in abstinence by year 1 and all the way until the 11th year.

Focusing on cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, heroin, inhalants, non-heroin opioids, sedatives, stimulants, tranquilizers, or other drugs, McCabe, Cranford, and Boyd (2016) analyzed the remission rates of their 3-year longitudinal study featuring 921 people. Substance use disorder was measured following the criteria of the DSM-IV through the AUDADIS-IV. For all these types of drugs, the majority of people in Wave I and II were in abstinence.

Unfortunately, they did not break remission rates by type of drug, but this will be an issue dealt with later. Regardless, it does seem like these findings still support the idea of high remission rates among drug users, in contrast to the idea that drugs are addictive for most people.

Lopez-Quintero et al. (2010) used a nation-wide representative sample of addicts (i.e., people who fit the DSM-IV criteria) who did nicotine (n=6,937), alcohol (n=4781), cannabis (n=530), and even cocaine (n=408). Much like the prior studies, there was a high probability of remission rate as time went on for all groups.

Even hard drugs like cocaine, for example, seem too high remission rates as time goes on for individuals. These findings further cast doubt on the validity of addiction for most people, and if those who continue to use it are actually addicted or if there are other pre-existing risk factors that lead to abusing drugs.

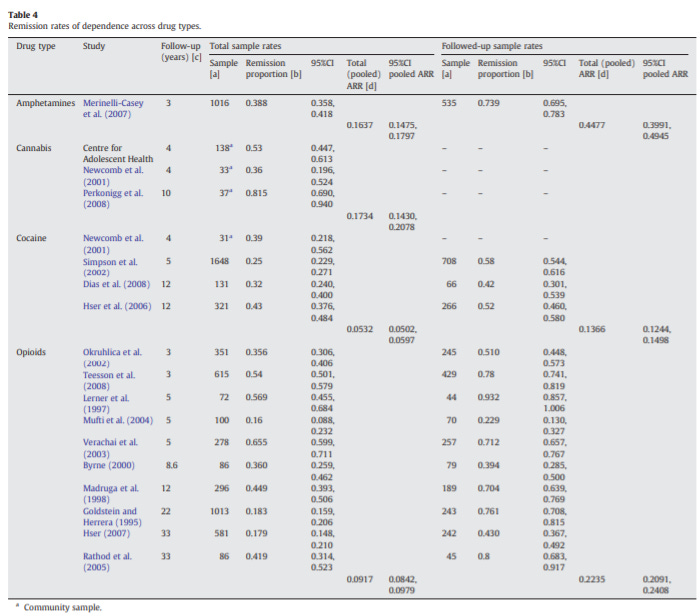

These findings have been further corroborated by a systemic review looking at the remission rates for amphetamine, cannabis, cocaine, and opioid dependence. Calabria et al. (2010) looked at studies looking at the remission rates for a dependence on different types of drugs and, although they found medium-high remission rates, the remission rate differed by type of drug.

For amphetamines, the remission rate was 0.448; for cocaine, the remission rate was 0.137, and for opioids, it was 0.223. From this systemic review, the remission rates seem much lower than in the prior studies. However, there are significant issues with this analysis.

First, 9/17 (52%) of the studies included in the analysis were on people seeking treatment. Why is this an issue? People who seek treatment may not be representative of drug users, to begin with. As Heyman notes, most people who meet the criteria for “addiction” never go to treatment. One 1991 study cited by Heyman found that in one large national survey, only 30% of the sample who met the criteria for being an addict went to treatment, and another 2005 study with 43,000 people had 16% actually in treatment. Because of an issue called “Berkson’s Bias“, which refers to the fact that people in treatment are more likely to suffer from additional disorders, it’s possible that those in treatment may simply be more likely to relapse, and this distorts the actual remission rate in the top review.

Those in clinics seeking help for drug use may be more likely to relapse than those outside of these clinics, an issue since this population has characteristics associated with not quitting drugs. Klingemann, Sobell, Sobell (2010) note that the idea of drugs being a chronic disorder was based on samples of people with certain characteristics that predicted not stopping the use of drugs, so it’s hard to take clinical samples seriously because of this issue. In the ECA survey noted above, 64% of those in clinics had at least 1 additional psychiatric disorder, and, as Heyman notes,

The more recent and larger NIAAA survey reports similar results (Stinson et al., 2005), as do smaller studies. For instance, in two reports from drug clinics associated with Yale Medical School, the rate of comorbidity for cocaine and heroin addicts was 74 and 87 percent, respectively (Rounsaville et al., 1991; Rounsaville et al., 1982).

Heyman offers the graph above, using it to argue that people with additional psychiatric disorders may use drugs to help their pre-drug issues. Someone with issues like anger, for example, may turn to drugs to alleviate these issues, and because they seek treatment, they are not representative of the general population of drug users and thus those in treatment are more likely to relapse. The same findings of poly-drug use among clinical samples have also been found in marijuana, the issue that might lead to the idea that cannabis actually is addictive (Hubbard et al. 1989; Didcott, Flaherty, and Muir 1988).

Because of these issues, it’s important to separate clinical samples from population-based samples, a pitfall also experienced in a 2016 meta-analysis on the issue by Fleury et al. (2016).

A very recent 2022 study also found that most people can stop using drugs if they want to. What separates this study from the rest is their inclusion of not just drugs, but pornography/ sex addiction (I doubt these things are addictions overall, but let’s ignore this for now), video-game addiction, and compulsive shopping. Goodings, Williams, and Williams (2022) looked at 2 longitudinal studies from Canada and measured substance use disorder based on the DSM-IV criteria gambling disorder, and other excessive behaviors (pornography/sex, shopping, gaming).

As can be seen in both longitudinal studies, the majority of people stopped abusing substances and saw a decrease in excessive behavior, gambling, gaming, and pornography/ sex. For those with multiple addictions, the values were higher, but those with multiple addictions could have had prior existing-risk factors which lead to poly-addictions, something not investigated in this study but that warrants further research.

Another issue with these addictions is the issue of genetics. Bevilacqua and Goldman (2009) offer the graph below showing the heritability of “addictions” like cannabis and gaming, for example.

Cocaine has the highest heritability estimate of all, but this clearly shows moderate-large heritability estimates for different addictions. Because of this, it’s worth asking if drugs themselves are really addictive as people make them out to be, or if people with certain risk factors, like genetic predisposition to “addiction”, simply lead to one abusing a certain substance rather than the substance itself being addictive somehow. GWAS studies can help us see which genes lead to “addiction” and how they work.

Addiction, then, seems to be an issue that doesn’t affect most people, and those that do may have pre-existing issues rather than a drug issue itself. It’s an addiction of choice in a sense, not stimulus. That most people aren’t addicted to cannabis was also found in 1991 by the U.S. Department of Health (85).

“Given the large population of marijuana users and the infrequent reports of medical problems from stopping use, tolerance, and dependence are not major issues at present”

That cannabis may not be addictive is also supported by the findings that when experts are asked how easily a drug can hook someone and make it hard for them to quit on a scale of 1-100, marijuana is ranked very low when compared to other things and is rated at 20 on the scale (Franklin 1990, in McWilliams 2011). This, of course, is one piece of evidence that marijuana itself is not addictive, along with the remission studies above, but there is more evidence.

First off, most people who use cannabis do not go on to use it regularly (Roffman et al. 1993). A study of 42,000 people found that for those who used marijuana in the past year, 23% qualified for a diagnosis and 6% qualified for a diagnosis of dependence. Dependence was seen more often in depressed users (Grant and Pickering 1988 [remind you of how depressed individuals may seek cannabis?]). Most users (85%, according to the study) also do not experience issues related to social functioning, health troubles, or psychological symptoms (NIDA 1991), and another study found that only 9% of people in their longitudinal sample reported issues (Weller and Halikas 1980).

Focusing on withdrawal symptoms, which is often a go-to point for people who argue that marijuana is addictive, many studies have found that when high-dosing marijuana users stop using cannabis, withdrawal symptoms rarely occur among these individuals (Stefanis et al. 1976; Mendelson 1984 [case study, high doses of THC]; Greenberg 1976; Shuckit et al. 1999). Smith (2002), however, is critical of experimental studies on the issue. He notes that earlier studies on the issue tended to use clinical samples, an issue we already noted as being bad since clinical samples are not representative of the general population. Past studies have also had many issues, like differences in how cannabis was taken, and the use of ethanol which can confound the results. Differences in THC levels being administered also may not reflect THC levels in the real world, as THC concentration may have increased over time or probably not. An important note is that the laboratory setting may lead to changes in behavior that we probably wouldn’t see outside the lab. As Smith notes,

Environment has been shown to play an important part in mediating drug-effects. Conditioning to surroundings has been show to alter levels of arousal and motivational states as regards drug-taking (Stewart, de Wit & Eikleboom 1984). Rats addicted to morphine show physiological and behavioural signs of withdrawal when in the cage where the addiction was engendered; when taken off morphine and placed in a different environment the withdrawal effect is not apparent (Thompson & Ostlund 1965). This gives a physiological reason for being cautious in extrapolating from the laboratory to a naturalistic setting

Individuals in the study also might bias the results. Those with attitudes towards marijuana, specifically that the drug has no effects, tend to show “lesser effects than ambivalent individuals receiving similar doses.” The presence of symptoms itself also may not be accurate. As Smith says when discussing some symptoms of withdrawal:

The symptoms seen in the withdrawal studies do not necessarily form a consistent pattern. Greenberg and colleagues studied the behavioural effects of intoxication in individuals who smoked cannabis for 21 days. Neither observation by staff or self-report by participants revealed any adverse consequences of abstaining in the 5 days after ceasing the drug (Greenberg et al. 1976). Jones and colleagues professed to find sleep reduction, restlessness, irritability, sweating and chills in around 40–90% of participants. However, these symptoms were encountered ‘at least once’ by the individuals; further details on the incidence, duration and severity of these symptoms as they appeared in the individual sufferer were not reported (Jones et al. 1976)

Other things, like sleep problems, for example, have been found in many studies, but how marijuana was taken could bias the results. If ceased orally, there is no sleep disturbance, but if ceased when it was smoked, there is. More importantly, Smith says that the prevalence of symptoms is questionable. Self-reports tend to show higher estimates of withdrawal symptoms, but more standardized clinical tools show lower estimates. This could be due to a bias known as initial elevation in which people overestimate self-reported data for subjective states, and this includes addiction-related items, too (Shrout et al. 2017). Smith also says that “Cannabis users are not the same as dependent cannabis users in the incidence of withdrawal symptoms and withdrawal studies that do not make this distinction will probably find variations in the prevalence of symptoms.”

Furthermore, when withdrawal symptoms do occur, they tend to be “mild and transitory” and last a few days (Jones, Benowitz, and Bachman 1976). Although marijuana can cause withdrawal symptoms, this is not proof of addiction itself, nor is it special to drugs. As was said by the Institute of Medicine,

“Tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal are often presumed to imply abuse or addiction, but this is not the case. Tolerance and dependence are normal physiological adaptations to repeated use of any drug. The correct use of prescribed medications for pain, anxiety, and even hypertension commonly produces tolerance and some measure of physiological dependence. Even a patient who takes medicine for appropriate medical indications and at the correct dosage can develop tolerance, physical dependence, and withdrawal symptoms if the drug is stopped abruptly rather than gradually. For example, a hypertensive patient receiving a beta-adrenergic receptor blocker, such as propranolol, might have a good therapeutic response; but if the drug is stopped abruptly, there can be a withdrawal syndrome that consists of tachycardia and a rebound increase in blood pressure to a point that is temporarily higher than before the administration of the medication began.”

Population studies have also shown most people do not face withdrawal issues from cannabis, but clinical samples do. Population-based studies find the prevalence of cannabis withdrawal symptoms to be at 17%, and clinical samples at 54% and 87% (Bahji et al. 2020). This is not what we would expect if cannabis withdrawal symptoms were a serious issue among most cannabis smokers. And as was noted above, clinical samples tend not to be representative of the average person.

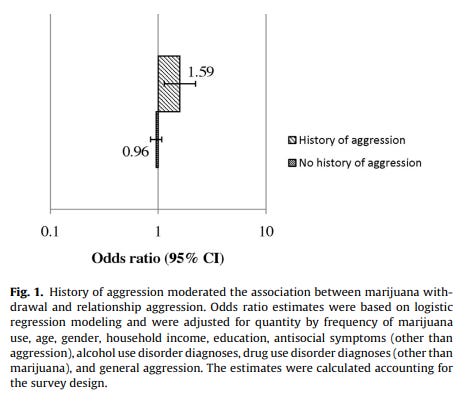

That some people do experience cannabis withdrawal symptoms doesn’t mean that cannabis necessarily causes these issues, to begin with. Personality can confound the relationship between cannabis use and withdrawal symptoms. For example, Smith et al. (2013) found that cannabis use did not increase general aggression among cannabis users, but did increase relationship aggression. However, this was only true for individuals who were already aggressive and not for individuals who weren’t aggressive. Higher relationship aggression can be attributed to pre-existing aggression but also differences within couples (Testa and Brown 2015).

Increases in marijuana use also aren’t permanent and return to pre-withdrawal levels after 28 days or so (Kouri, Pope Jr., Lukas 1999; this study did not adjust for personality). As Smith notes, older studies have also used people with pre-existing mental issues, and one study selected for those without pre-existing mental issues found no withdrawal effects and others reported clinical examinations but not past psychiatric history. In one study making use of the MMPI, a personality measurement,

“The only study to investigate the possible effects of personality on the appearance of withdrawal symptoms following cessation of cannabis use utilized the Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory (MMPI; Hathaway & McKinley 1951) to discover a particular group of traits that appeared to be related to the effects of abstaining from the drug, including anxiety, dependency and ego strength (Bachman & Jones 1979). Factor analysis of the results revealed a trait of ‘ego weakness’ in those experiencing withdrawal symptoms. These results concur with studies into benzodiazepines which link withdrawal severity and treatment outcome to ‘dependent personality’ traits (Rickels et al. 1988; Rickels et al. 1999).”

As the paper further notes, “individuals with dependent personality traits; a dependent personality attempting to stop using a certain substance might be more likely to seek help actively and exaggerate the symptoms experienced in an attempt to gain more help (Bornstein 1992). Dependent personality traits largely consist of passivity, helplessness, a need for interpersonal assurance, and a weak self-concept (Greenberg & Bornstein 1988).” Thus, personality can confound the severity and prevalence of withdrawal symptoms from cannabis. Smith also makes note of alternative explanations for withdrawal symptoms, like the release of biological chemicals unrelated to THC that lead to symptoms seen in withdrawal, but this is not the lack of THC causing this.

Because of this, I do not think marijuana itself is actually addictive, but rather pre-existing issues along with biological variables lead to cannabis abuse which makes it seem like it’s addictive. Withdrawal symptoms, while they might be present for some, are not an indication of addiction itself, is not unique to marijuana, and are confounded by personality.

In conclusion, there are many myths surrounding marijuana, and many of them — while not discussed here for the sake of keeping stuff short — are misleading or downright false. Happy 4/20, watch Dazed and Confused, listen to Black Sabbath, and have fun. Be responsible with your drug use of any kind and take care of yourself regardless.

Imagine thinking weed is not addictive smh

>4/20

>writing about marijuana and not daddy