On Sex Education

A look on the effects of sex education on different social outcomes, and young people's sexuality and how sex education benefits them

Sex education is a topic that might be good for some, bad for others, or good but requires restrictions on who is taught about sex education. In modern-day political commentary, some right-wingers have labeled the teaching of sex education among children as “groomer” behavior (Khazan 2022; CBS News 2022). Some conservatives seem to assume that teaching children (not adolescents) is a form of grooming and sexualizing children (Srinivasan 2022). The ever-so-not-annoying James Lindsay also argued that sex education has a Marxist history.

According to people like Lindsay, sex education grooms and sexualizes children. The typical comment among posts from Twitter users like Lindsay, Libs of Tik Tok, etc. argue that children should not learn about sex education because “children should be children.” According to Lindsay, it “disrupts childhood innocence". While this may seem like a plausible idea, it’s not how reality is, and conservatives seem unaware of the research surrounding child sexual development.

In this article, I am going to discuss the effects of sex education on sexual behavior, attitudes, and social and romantic relationships, and if sex education should be taught to children. This article may be more *controversial* for some of the stuff that may be said, but it’s only controversial if one doesn’t know the issue and instead assumes a perfect world.

Effects of Sex Education

Before talking about the effects of sex education, an important discussion about Thomas Sowell, a popular conservative commentator, and his discussion on sex education in his work should be discussed.

Thomas Sowell in The Thomas Sowell Reader heavily criticized sex education in the early 1960s to 1970s, claiming that the push for sex education was based on a crisis that did not exist. According to the purveyors of sex education, sex education would help reduce the number of incidences related to teen pregnancy, irresponsible sexual behavior, and sexual disease. However, Sowell argues that this crisis did not exist, and teen pregnancy and sexual diseases were declining among teenagers while sex education was being promoted (199-200, PDF).

Although Sowell is correct that teen pregnancy and sexual diseases were declining at the same time sex education was being promoted, his argument is based on the false assumption that supporters of sex education considered it a crisis, something his quotes do not support. Per the quotes Sowell references:

“contraception education and counseling is now urgently needed to help prevent pregnancy and illegitimacy in high school girls” - Family Planning Program

“to assist our young people in reducing the incidence of out-of-wedlock births and early marriage necessitated by pregnancy.” - Planned Parenthood

Where exactly do the quotes Sowell provides suggest that the purveyors of sex education wanted the program because of a “crisis” going on in society? Issues can exist without them being crises and still warrant a program to help lower the incidences of these issues. Sowell seems to manufacture a crisis on his own to better attack sex education programs. Sowell then says,

Critics opposed such actions on various grounds, including a belief that sex education would lead to more sexual activity, rather than less, and to more teenage pregnancy as well. Such views were dismissed in the media and in politics, as well as by the advocates of sex education (201).

As Sowell points out, supporters of sex education were quick to dismiss these beliefs, and Sowell notes how teen pregnancy and abortion rose from the 1970s to the mid-1980s, all while sex education was being promoted. According to Sowell, this evidence suggests that sex education did not do what it was encouraged to do. However, there are issues with Sowell’s argument. Despite the manufactured crisis from Sowell, the reason for an increase in teen pregnancy and abortion from the 1970s to the mid-1980s was not because sex education failed, but rather ignorance that led to an increase in sexual behavior. As Adame (1985) notes,

“Our research tells us that ignorance, not knowledge, leads to irresponsible behavior, In fact, knowledgeable young people are more likely to begin having sexual experience later than their less knowledgeable peers and then to use effective contraception” (10).

Ried (1982) takes a different position than Adame, instead of saying that lack of anticipation, not ignorance, leads to teen pregnancies. (Ried notes how sex education did not lead to long-term gains in knowledge about sexuality, but I believe this is because that sex education was not very comprehensive at the time, an issue discussed below._

Other data at the time also does not support the cause-and-effect argument that Sowell is making (i.e, that sex education led to an increase in teen pregnancies and other issues).

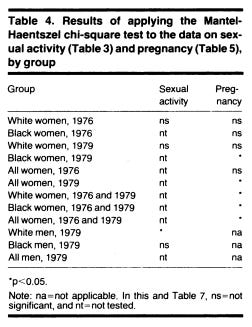

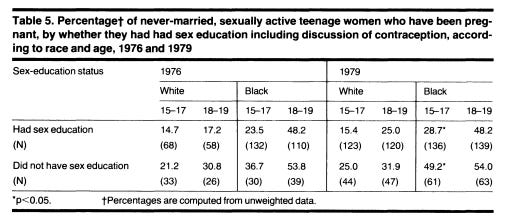

Zelnik and Kim (1982) analyzed data from two national surveys which included those who had sex education in 1976 and 1979. Once using a specific chi-square test, they found no relationship between sex education and sexual behavior, showing that sexual education has null effects on the odds of having sex or not, except for white males in 1979.

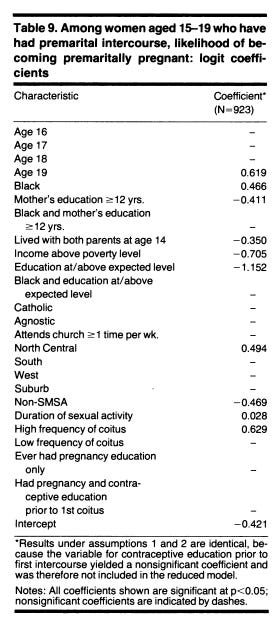

When looking at the effects of sex education on teen pregnancy, those who did not have sex education were more likely to become pregnant than those who did, but the differences tended not to be statistically significant but do seem practically significant (see the table above, and for a refresher on p-values, see Kline 2013 and Wasserstein, Schirm, and Lazar 2019).

As the authors note, “There appears, then, to be fairly strong support for the argument that never-married, sexually active young women who have had sex education experience fewer pregnancies than those who have not.” When looking at the use of contraceptives by race, black women who took sex education were more likely to use contraceptives than those who did not, and among whites, there was no relationship between taking sex education or not and using contraceptives or not.

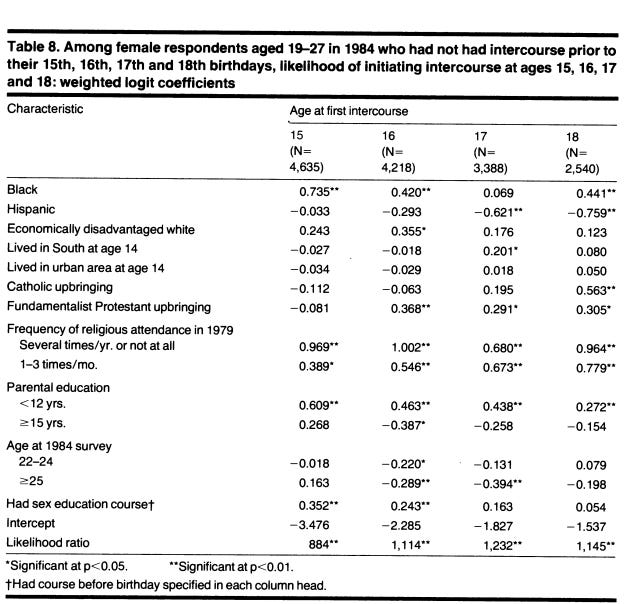

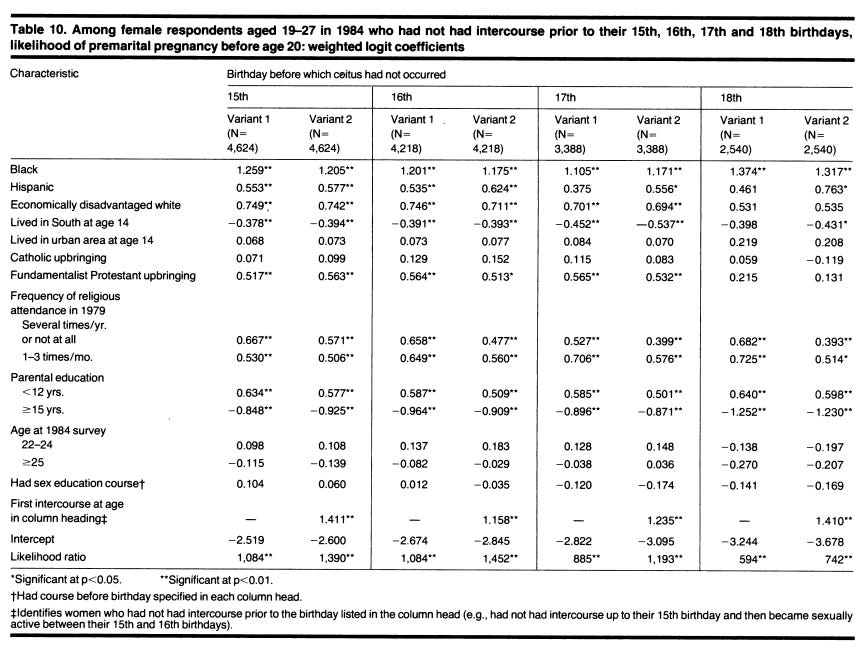

Marsiglio and Mott (1986) looked at data from the first wave of the NLSY 1979.

Being black, Hispanic, having a fundamentalist protestant upbringing (for ages 16-18), frequency of religious attendance, and parental education being < 12 years, had a stronger positive effect size on age at first intercourse than did having had a sex education course. So, while having taken a sex education course was positively associated with having sex, it was only significant at ages 15 and 16, but it was not the strongest predictor and was beaten out by many other variables.

Focusing on the likelihood of having a premarital pregnancy, having had a sex education course was not significantly related to having a premarital pregnancy, contra critics.

Dawson (1986) found no consistent relationship between exposure to contraceptive education and subsequent initiation of sexual intercourse among adolescents through the National Survey of Family Growth. A relationship was found among 14-year-olds, but this was under an extreme assumption. However, females who received formal instructions about pregnancy and birth control have better knowledge about contraceptives than those who didn’t know this information. Furthermore, “neither pregnancy education nor contraceptive education exerts any significant effect on the risk of premarital pregnancy among sexually active teenagers-a finding that calls into question the argument that formal sex education is an effective tool for reducing adolescent pregnancy.”

Kirby (1985) reviewed pre-test-post-test data from the CDC on sex education and sexual behavior. According to Kirby,

The study found that none of the sexuality courses had a measurable impact on whether or not the participants had experienced sexual intercourse or whether the participants had engaged in sexual intercourse during the previous month or the number of times participants had sexual intercourse. The courses did not appear to affect the incidence of sexual intercourse.

Kirby also discussed the Zelnik and Kim study cited above. Other studies also found no relationship between sex education and pregnancy. However, scholars, according to Kirby, argue that changing behavior through school is difficult, and giving them the knowledge about these things might be better.

However, the null results, I believe, are due to the lack of comprehensive sex education at this time. While the effects are null, I do not expect them to fit in line with current sex education where what it teaches differs from sex education in the 70s to 80s. Indeed, as Muraskin (1986) reviews, sex education at the time was not the most comprehensive.

“It is not uncommon for a high school health education teacher to describe the topics she covers as follows: ‘I do a week of drugs, a week of alcohol, a week of communicable disease, a week of sex, a week of smoking, a week of nutrition and a week of dental hygiene.’ Teachers appear to be perfectly comfortable with the idea that if they discuss a topic briefly, they have ‘done’ it.”

Teachers were poorly trained to discuss things related to sexuality and family life education, and some topics were discussed so quickly as the quote above notes. This sex education was not comprehensive, which probably explains why the effects were null.

Jorgensen (1981) notes that research at the time failed to find a relationship between sex education and lower teen pregnancies, but this was due to barriers that minimized the effectiveness of sex education rather than issues with sex education itself. As Jorgensen notes, there are multiple barriers standing in the way of effective sex education. One of them is conservative groups who are against teaching sex education, but most parents at the time supported sex education and formal discussions about contraceptives. Of course, teen pregnancies will rise if all you try to do is stop teenagers from having sex, but teen pregnancies can curb if you also teach about contraceptives rather than trying to reduce the former but not increase the other.

Another barrier noted is planned pregnancies among adolescents. As Jorgensen notes, some studies at the time estimated the rate of planned pregnancies among adolescents at the time to be 30% to 40%. Cognitive development also plays a role, as Jorgensen argues. There might be a mismatch between what sex education courses were taught at the time and the cognitive level of some students who couldn’t properly internalize and understand what sex education was teaching. The course may simply not “fit” certain people with different cognitive levels, thus leading to null effects or opposite effects. As Jorgensen notes, sex education will have no or little effect on teen pregnancy if educators don’t acknowledge individual differences in cognitive development.

Another barrier to sex education effectiveness is attitudes towards gender norms. Individuals with more traditional views of gender norms are more likely to risk pregnancy by having sex more often and using contraceptives less often. Since these individuals believe that a woman must conform to a man’s desires, they would be less likely to use contraceptives, as evident by the studies cited by Jorgensen. This is akin to Trussell (1988) who found that some populations may not see a benefit in postponing having a child. The final barrier offered by the author is the lack of parental knowledge, support, and involvement. Parents tend to be underutilized when it comes to learning about sex, and information about sex then comes from other places, like magazines or one’s partner.

Because of these issues, I do not think we should take the null effects at face value due to the lack of comprehensive sex education during this time and the many barriers stopping sex education from being effective.

Sowell does not bring up these studies and instead says that teen pregnancies were increasing while sex education was being promoted. Sowell argues that the increase in teen pregnancies clearly shows sex education to have failed in reducing what supporters wanted it for, but this is not due to the failure of sex education, contra Sowell. Instead, it seems that the lack of comprehensive sex education and the barriers facing it might have stopped it from having a large effect or any effect at all. Sowell’s failure to provide this data shows that once it’s viewed, Sowell is wrong.

Sowell accuses sex education of being a form of “indoctrination”, saying that

In short, however politically useful public concern about teenage pregnancy and venereal disease might be in obtaining government money and access to a captive audience in the public schools, the real goal was to change students’ attitudes —put bluntly, to brainwash them with the vision of the anointed, in order to supplant the values they had been taught at home. In the words of an article in The Journal of School Health, sex education presents “an exciting opportunity to develop new norms.”

How is learning about homosexuality, which was taught at that time and still is, a form of indoctrination? How does learning that some people have sex with same-sex brainwash people? That learning that sexuality is more than just a man and women is only an issue if one believes that adolescents learning about it is bad — and then the question becomes “why?” Why is learning about homosexuality bad? Is it because people will become more tolerant of homosexuals? If so, why is this bad?

Sowell doesn’t answer these questions, instead just saying that learning new values is a form of brainwashing. Sowell’s views on sex education leave more questions than answers, and his failure to provide a valid criticism towards it shows by the lack of cited studies done at that time examining the effects and issues stopping sex education from being effective. Modern studies provide similar but also different effects of sex education — at least comprehensive sex education.

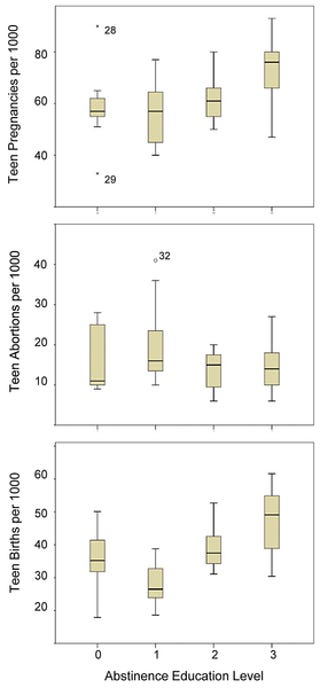

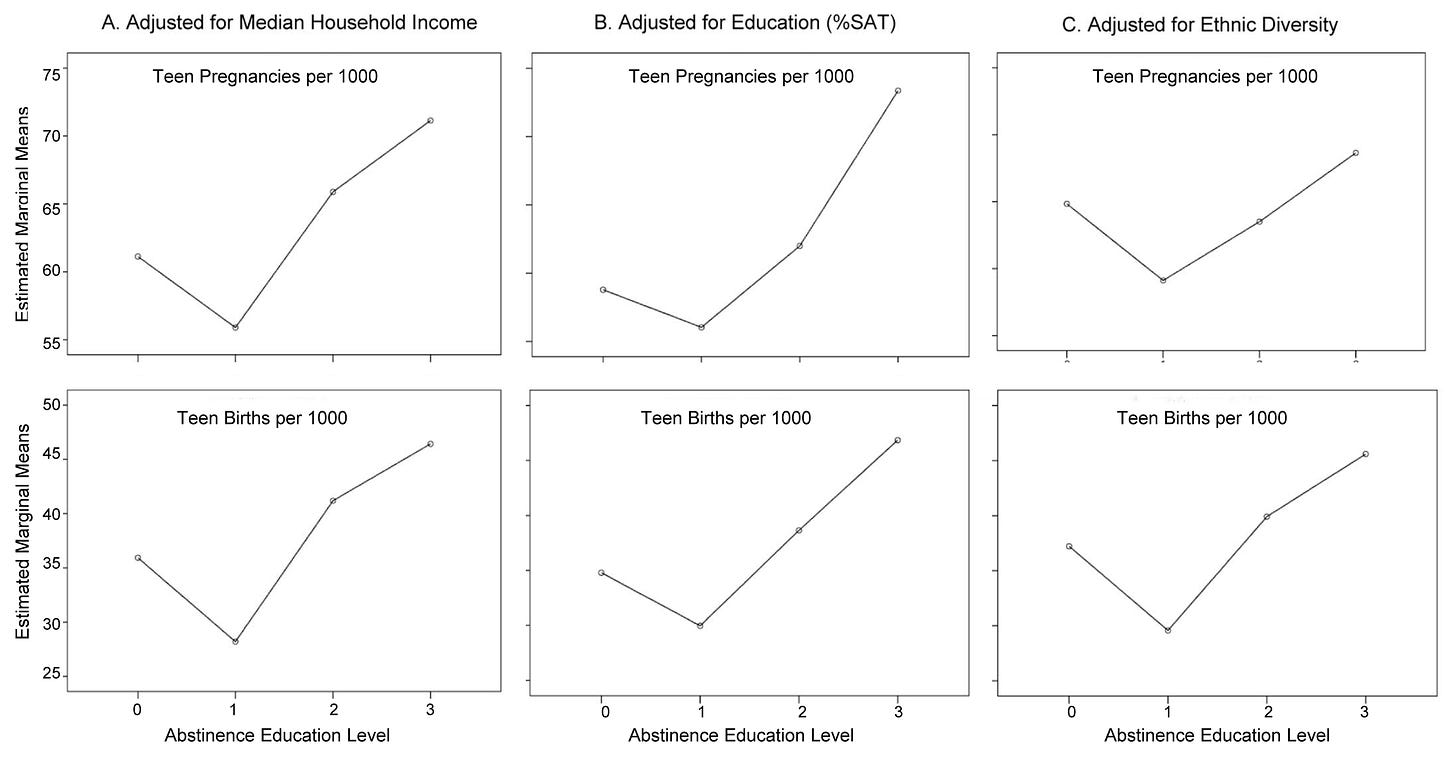

Stranger-Hall and Hall (2011) compared the effectiveness of sex education by comparing 30 states which had sex education in 2007 with no comprehensive sex education and those with comprehensive sex education. The ordinal scores varied from 0 to 3. A high score indicated more emphasis on abstinence until marriage if HIV/ STD education is discussed. A score of 2 indicated “abstinence in school-aged teens if sex education or HIV/STD education is taught, but discussion of contraception is not prohibited.” A score of 1 indicated abstinence for school-aged teens, which includes medically accurate information about contraception and protection from STIs, and a score of 0 does not specifically mention abstinence. In other words, a higher score means it’s less comprehensive, and a lower score indicated it was more comprehensive.

Teen pregnancies were higher in places with less comprehensive sex education. However, teen abortions were not associated with sex education, a finding in prior studies noted above when responding to Sowell. Teen births were higher in states with sex education levels at 2 and 3, but lower for 0 and 1 but 0 was higher for 1. Thus, only focusing on abstinence before marriage might lead to counterintuitive results.

When adjusting for mean household income, education, and ethnic diversity, results were still similar.

Teen pregnancies and births were still higher in places with less comprehensive sex education, even after adjusting for multiple possible confounders.

The issue of teenagers being sexually active, and thus having abstinence sex education not work, are an issue found in a review of the literature by Santelli et al. (2017). According to the authors,

The most useful observational data in understanding the efficacy of abstinence intentions comes from examination of the virginity pledge movement in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (Add Health) [37,38]. Add Health data suggest that many adolescents who intend to be abstinent fail to do so, and that when abstainers do initiate intercourse, many fail to use condoms and contraception to protect themselves [37,38]. Other studies find higher rates of human papillomavirus and nonmarital pregnancies among adolescent females who took a virginity pledge than those who did not [39]. Consequently, these studies suggest that user failure with abstinence is high.

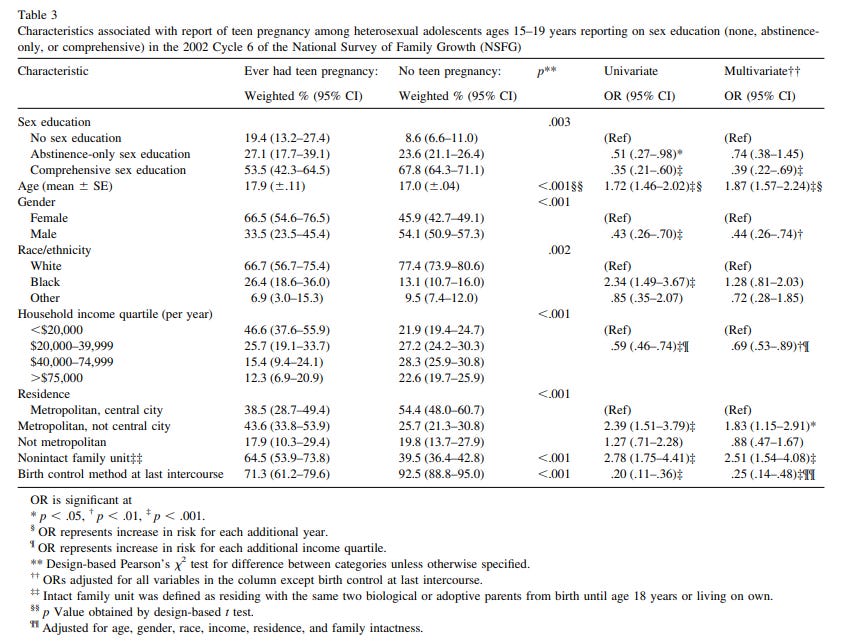

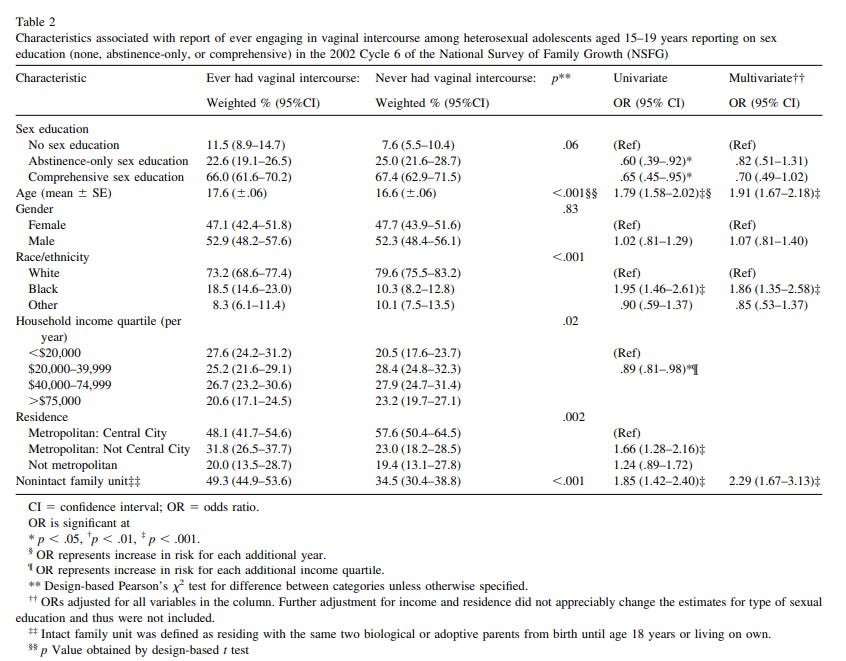

Similar results were found in Kohler, Manhart, and Lafferty (2008) who looked at data from the NSFG. Abstinence-only sex education was associated with higher teen pregnancy, but comprehensive sex education was associated with lower odds of teen pregnancy.

Similar results were found when looking at vaginal intercourse. Abstinence-only did not decrease the odds of engaging in vaginal intercourse, but comprehensive sex education was marginally associated with low odds. Different types of sex education did not affect reported STDs.

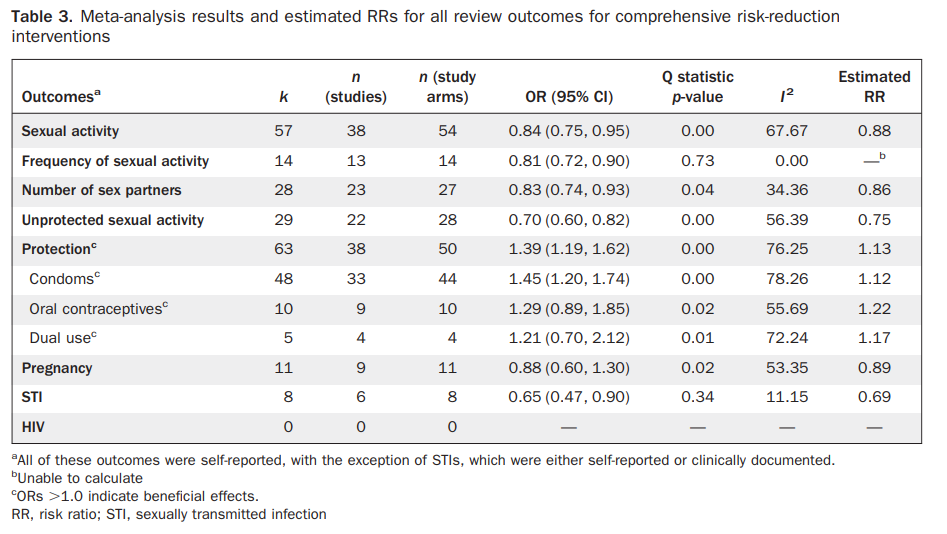

Chin et al. (2012)’s meta-analysis on the effects of comprehensive risk-reduction interventions, which are interventions that “promote behaviors that prevent or reduce risk of pregnancy, HIV, and other STIs”, found that they were associated with lower odds of sexual activity, frequency of sexual activity, number of sex partners, unprotected sexual activity, and an increase in the odds of using a condom, contraceptives, or both. It was also associated with lower odds of pregnancy and STIs.

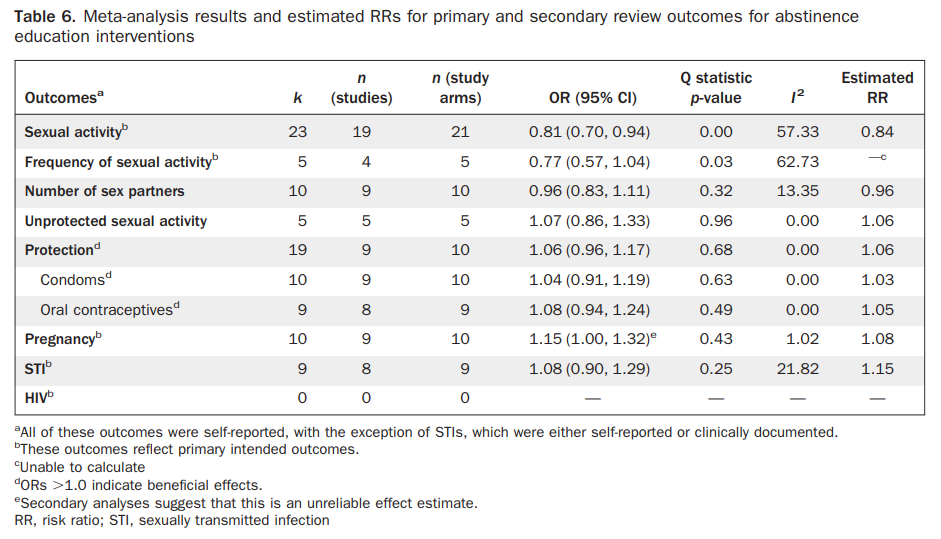

The effect of pregnancy was not statistically significant, but the effect does seem practically significant. Abstinence education provided similar effects, but with some important caveats.

First off, while it did decrease the odds of sexual activity and frequency of sexual activity, this was due to differences in study design. Pregnancy and STIs showed higher odds, but the effects were weak as STIs had an increase of 7% and pregnancy was larger at 15%. As the authors said, “The ORs for the secondary abstinence education outcomes number of sex partners, unprotected sexual activity, and use of protection during sexual activity was close to unity and not significant.” Furthermore, there was evidence of publication bias for abstinence studies as smaller samples provided greater effects. Does not seem like studies looking at the effects of abstinence-only education provide positive effects not biased by something.

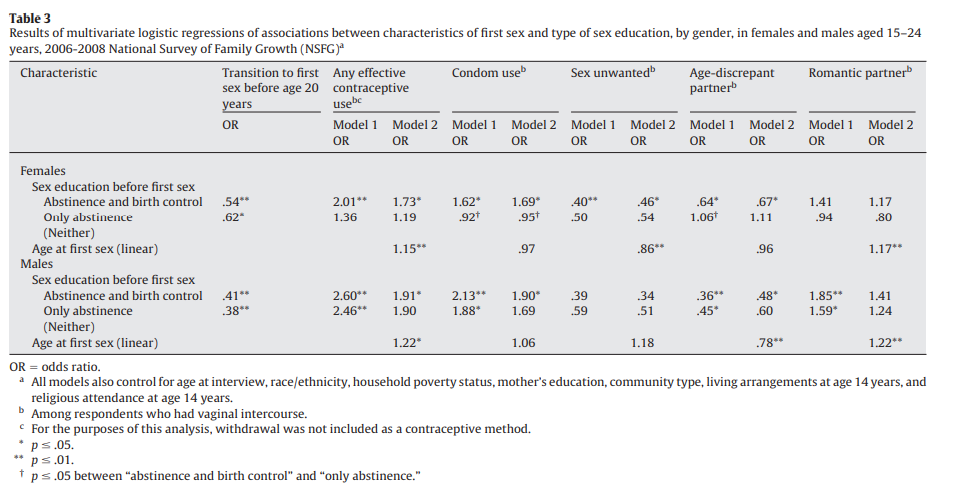

Lindberg and Maddow-Zimet (2012) used data from the 2008 NSFG and measured the effects of different types of sex education (only abstinence, abstinence, and birth control, or neither) before sexual intercourse, and sexual behaviors and different outcomes.

Abstinence and birth control education had statistically significant and stronger effect sizes on any effective contraceptive use, using condoms, lower chance of having unwanted age, a lower age-discrepant partner, and an increase in the odds of having a romantic partner. Abstinence-only, on the other hand, did have a positive effect on contraceptive use (19% increase), but it wasn’t statistically significant, less likely to lead to condom use, lowered the odds of having unwanted sex, increased the odds of having an age-discrepant partner, and a decrease in the odds of having a romantic partner. All of this was for females, of course.

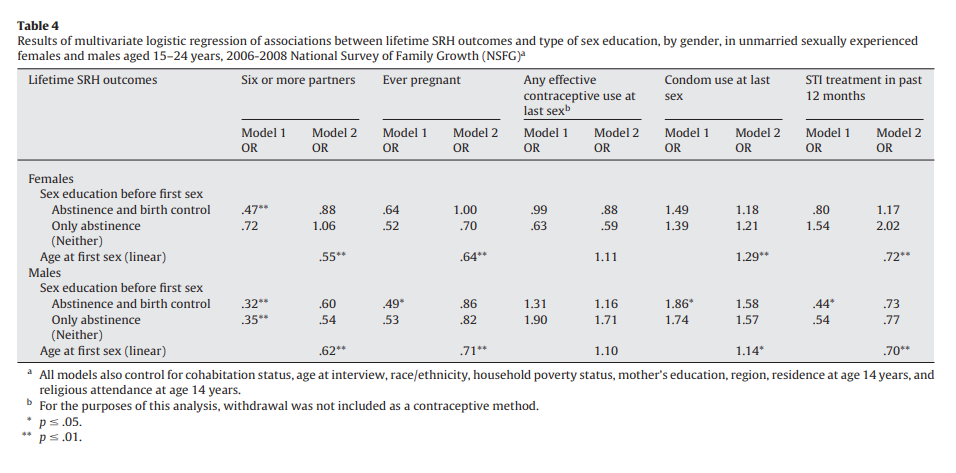

For males, both abstinence and abstinence and birth control had significant effects across the board, except in the odds of having a romantic partner. Table 4 offers more effects of sex education on having 6+ more partners, ever being pregnant using contraceptives and condoms last time when having sex, and having an STI treatment in the past 12 months.

Abstinence and birth control led to a lower odds of having 6+ partners, were not associated with getting pregnant, were less likely to have used any effective contraceptive use the last time having sex, and had a higher odds of using a condom the last time they had sex and had a higher odds of getting an STI treatment in the past 12 months. However, none of these effects were statistically significant for females. Only abstinence was associated with a 6% increase in having 6+ partners, lower odds of getting married, lower odds of using an effective contraceptive and using a condom the last time when having sex, and a 2-fold increase in having an STI treatment in the last 12 months. Again, most of these effects were not statistically significant.

For males, abstinence and birth control and abstinence-only were associated with 6+ partners, lower odds of getting pregnant, more likely to use a contraceptive and condom last time when having sex, and lower odds of having an STI treatment in the past 12 months. Again, most of these effects were not statistically significant.

When discussing the lack of statistically significant findings, the authors say,

“We believe that the lack of many significant differences between receipt of only abstinence and Ab BC derives, at least in part, from our inability to identify details of the instruction about birth control measured in the NSFG. Reported birth control instruction may promote the use of contraception or only discusses failure rates and ineffectiveness as required by federal abstinence-untilmarriage legislation. We expect that reports of receipt of birth control instruction fall into both camps, diminishing the “realworld” differences between our analytical categories. Future efforts to measure receipt of sex education must better distinguish the tone and content of birth control instruction.”

In other words, they didn’t have much information about the quality and quantity of education for sex. While this study offers findings that would diminish our trust in sex education, this could be because there was little information on the quality of the sex education offered.

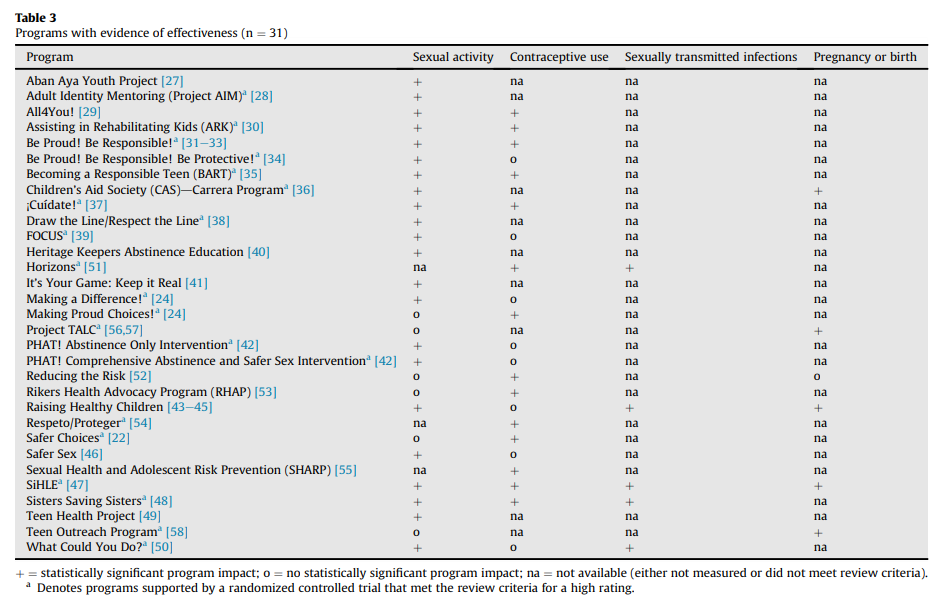

Goesling et. al (2014) conducted a systematic review of multiple studies in which most were randomized control trials. Interestingly enough, this study also included studies on elementary schools, and included abstinence-based, clinic-based, sexuality education, and others but the rest were for special populations.

Most of the studies on STIs and getting pregnant or giving birth were not measured in the studies or simply didn’t meet the review’s criteria. However, the majority of studies found that it decreased sexual activity, and led to better contraceptive use. The studies on the final 2 columns have missing data because these things were not measured in the study or did not fit the criteria for the review, but if we want to see what they found, 5 led to lower STIs, and 5 had an impact on pregnancy or birth. Seems they find positive effects for the last 2 columns, but most studies did not measure these things, to begin with. Unfortunately, the authors did not break down the results by education type (i.e, abstinence-only, etc.) I looked at one random study that was on this from their sources, and the study found that abstinence-only did not affect STIs in high-income countries.

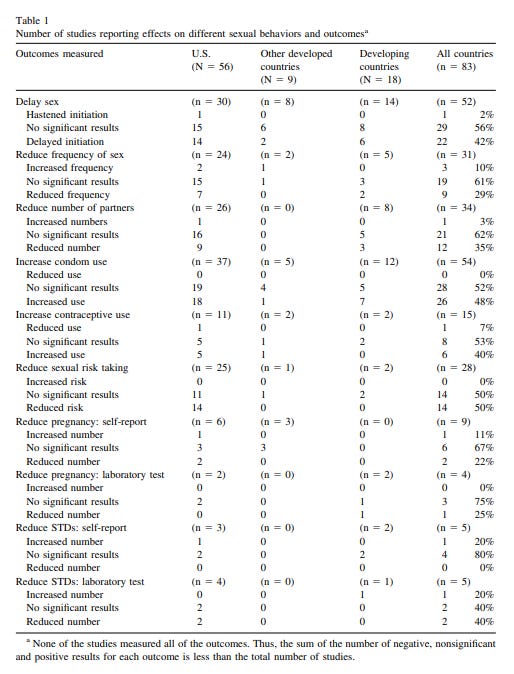

Kirby (2012) looked at 83 papers measuring the effects of sex education on a variety of things. For this, we’ll focus on the U.S. only since other countries may have too many confounders that don’t allow them to be applicable to the U.S.

The majority of studies did not find sex education to delay or hasten sex or sexual frequency, which I don’t think should be an important outcome to be focused on since I do not think that adolescents having sex is an issue — but this may depend on how one views sex, to begin with. The effects of the other studies were mostly mixed, with some finding an effect or no effect, and others finding null effects. However, I caution Kirby’s review since there may be many limitations, as Kirby notes.

“Formal meta-analyses of all of these studies should be conducted so that they can overcome some of the limitations of the individual studies (e.g., insufficient statistical power).”

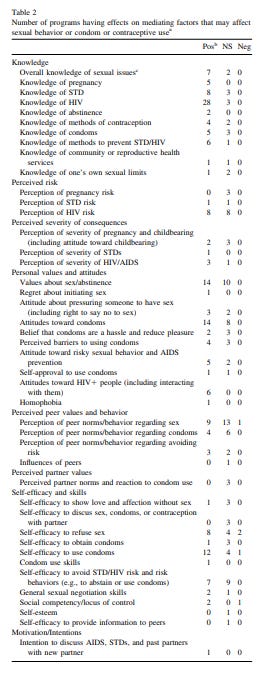

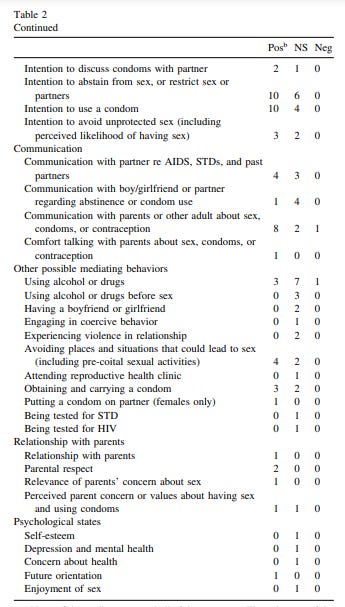

However, Kirby’s review of sex education’s effects on knowledge about sexuality offers promising results.

Sex education led to positive effects on knowledge about pregnancy, STDs, HIV, abstinence, methods of contraception, condoms, and methods to prevent STIs/ STDs, but mixed findings on knowledge of the community or reproductive services, and negative effects on limits on one’s own sexuality. However, the table is really long and this isn’t really a formal study, but many studies found positive results on sexual knowledge, and others found mixed or negative results, but it depends on knowledge about what. Readers interested in this can see table 2 above and below.

As Kirby says,

Of those programs that measured impact, most increased knowledge about HIV, STDs, and pregnancy (including methods of preventing STD/HIV and pregnancy). Half of the 16 studies that measured impact on perceived HIV risk were effective at increasing this perceived risk. More than 60% of the many studies measuring impact on values and attitudes regarding any sexual topic were effective in improving the measured values and attitudes. About 40% of the 29 studies that measured impact on perceived peer sexual behavior and norms significantly improved these perceptions. More than half of those studies that measured impact on self-efficacy to refuse unwanted sex improved that self-efficacy, and more than two thirds increased self-efficacy to use condoms. Ten of 16 programs increased motivation or intention to abstain from sex or restrict the number of sex partners, and 10 of 14 programs increased intention to use a condom. Eight of 11 programs increased communication with parents or other adults about sex, condoms, or contraception. In contrast, less than 30% of the programs had a positive impact on use of drugs or alcohol, perhaps in part, because reducing use of alcohol or drugs was not the focus of these programs.

I do want to note that many of these studies were from the U.S. + other countries, so caution should be taken when seeing some of the effects and they could be biased.

Kirby notes when it comes to the studies looking at abstinence-only that,

“And finally, while there were only six studies that focused only on abstinence (all in the U.S.), there were a few positive results (and one negative result) for these programs, just as there were many positive results and a few scattered negatives results for the far more numerous programs that commonly emphasized both abstinence and condom or contraceptive use.”

Goldfarb and Lieberman (2020) are probably one of the most comprehensive reviews on the effects of sex education, with this review also including the effects of sex education on elementary school students. The studies reviewed by the authors found that comprehensive sex education led to an appreciation of sexual diversity (e.g., reduced homophobia, lower bullying, and harassment based on homophobia), with this being found from pre-school children to grade 12. As the authors note,

Other methodologically strong studies have found that LGBTQ-inclusive sex education is related to lower reports of adverse mental health (suicidal thoughts and suicide plans) among all youth and of experiences of bullying among sexual minority youth. As well, they are related to better health outcomes among gay, lesbian, and bisexual students, including fewer sex partners, less use of drugs or alcohol before sex, less pregnancy, and better school attendance.

Sex education helped expand the views of gender norms which allowed students to challenge and cross their own gender boundaries based on stereotypes.

“In one participant-observation study of a literature-based gender norms curriculum with suburban, Midwest AfricanAmerican fifth graders [36], the author reported that “over time.both girls and boys felt safe in discussing and challenging one another's assumptions about gender's role in their reading choices” (p. 384) and concluded, “Children need safe spaces in which to experience, play with, and begin to challenge the naturalized assumptions about gender.” (p. 384). The studies noted here, as well as one of a preschool class [25], highlight that young children are, in fact, quite capable of understanding and discussing issues related to gender diversity, including gender expectations, gender nonconformity, and gender-based oppression. They also underscore that the development of such understanding requires instructional scaffolding over a period, and not just one session.”

It also was associated with a better understanding of sexual social justice, like sexual oppression, rights, and equity. Importantly, sex education also led to a better understanding of preventing dating and intimate partner violence, attitudes about and reporting this type of violence, and a decrease in this type of violence. Sex education also led to better knowledge about healthy relationships, like communication, attitudes, and skills to improve a relationship, and intentions. When it came to child abuse,

“A strong metaanalysis of 27 preschool through Grade 5 programs [80] and a systematic review of 24 K-5 programs [83] demonstrate significant effects on a wide range of outcomes, including behaviors in simulated at-risk situations. Another large systematic review concluded that, in general, parental involvement, opportunities for practice, repeated exposure, and sensitivity to developmental level were key characteristics of effective child sex abuse programs [81].”

And, very importantly, sex education led to a better understanding of child abuse among kids and what counts as good and bad touching. Some additional benefits were social-emotional learning, like being able to speak up for one’s self, and media literacy, which was learning that media is often inaccurate about adolescent norms. This review did not focus on pregnancy and things alike, but rather on knowledge and attitudes about different things taught in sex education.

Overall, it seems sex education has many positive benefits, contra people like Sowell. Comprehensive sex education, specifically, seems to have the strongest effects when compared to abstinence-only. I believe the evidence suggests that sex education is a positive as it impacts many social outcomes in positive ways. Abstinence-only, though, doesn’t seem to have strong effects.

While sex education does seem to have positive effects, I think it’s worth mentioning if children should be taught sex education. According to people like Lindsay, sex education robs children of their childhood, because, as most people would say, why should children learn about sex? Well, the following section is going to be somewhat controversial to people unaware of childhood sexuality, but let me make the case.

Children and Sexual Education

I am going to argue that children should learn about sexuality (including sex, attitudes towards relationships, etc.) because children, whether we like it or not, are sexual, too.

P1: Children are sexual and curious about sexuality

P2: If P1 is true, children would benefit from sex education to promote a better understanding of sexual health and sexuality.

C: If both P1 and P2 are satisfied, children should be taught sex education.

I don’t know if these P things work like this, but I think they do, maybe. Because of this, let’s discuss P1.

Apparently, many people — like conservatives, for example — are unaware of children being curious about sexuality and that they engage in sexual acts with themselves and others. Instead, they believe childhood is free from these things, but this is really not the case. Harden (2014) takes the position of viewing adolescent sexuality through a sex-positive framework, something I will do, too.

As Ryan (2000) notes in an early review of the literature,

Numerous studies referred to the masturbatory behaviors of toddlers and preschool children (Blackman, 1980; Conn & Kanner, 1940; Constantine & Martinson, 1981; Ford & Beach, 1951; Galenson & Riophe, 1974; Kanner, 1934; Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948; Kinsey, Pomeroy, Martin, & Gebhard, 1953; Levine, 1957; Lewis, 1965; Martinson, 1973; Ramsey, 1943; Spiro, 1958). Such behaviors were often referred to as “genital” rather than “sexual” by parents and pediatricians, but the researchers described arousal patterns, orgasmic tension reduction, aspects of the child’s demeanor which suggested introspection (mental imagery) and behavioral patterns suggesting that children’s masturbatory activities were at times self soothing and tension reducing (when tired or stressed), and at other times stimulating and exciting (when bored or happy).

Notice the difference between parents and pediatricians when compared to what researchers noted: “but the researchers described arousal patterns, orgasmic tension reduction, aspects of the child’s demeanor which suggested introspection (mental imagery) and behavioral patterns suggesting that children’s masturbatory activities were at times self soothing and tension reducing (when tired or stressed), and at other times stimulating and exciting (when bored or happy).”

There does seem to be a sexual aspect to child masturbation, as evident by how the child would behave when doing this. In a survey given out by Ryan and colleagues at the 16th Annual Child Abuse Symposium and the 4th Annual Conference of the National Adolescent Perpetration Network in 1987, it was found that

“Respondents were 60% female/40% male and ranged in age from 26–80 (60% were age 30–40; 85% had grown up with siblings; 55% had frequent contact with cousins during childhood). As adults, 79.3% believed that childhood experiences with other children which they were reporting were “normal;” 9.2% “abnormal;” 8.0% “harmful.” As children, however, only 28.7% remembered feeling their experiences were “normal,” while “guilty,” “curious,” and “confused” were more frequently chosen as descriptors.

Being seen naked was an issue among the sample, but this says nothing about sexual experiences and more about being uncomfortable being naked around people like siblings. Ryan also discusses masturbation saying

“By age 12, half of the males had experienced ejaculation and over half of the females remembered orgasm; 60.7% had masturbated prior to age 12, 72.5 by age 18, and only 9.2 said they did not ever remember masturbating. Masturbation was either sporadic or continuous throughout childhood for 65.4%, although 45% of those believed (as children) that it was “harmful,” “sinful,” or “wrong,” 41.4% said it was “secret,” and only 18% said that as children they thought it was “OK.”

When discussing mutual masturbation and sex among children, it’s said that “Most considered their activities ‘consensual’ (60.9%); and few reported bribes (4%) or threats (6.9%). It is important to note, however, that acceptance of sexual interactions with ‘older friends’ did not extend to excuse sexual interactions of teenagers with prepubescent children.”

Important emphasis should be noted on children having sex with older friends, as nothing is said in this section is an excuse for children having sex with older friends or anything, rather than, contrary to popular belief, children are sexual and curious about sexuality. As McKee (2005) said, children engage in masturbation, ask their parents about sex at the age of 5, engage in sexual activities with other children, show their genitals to other children, and try to look at people undressing and nude pictures. Since most elementary schools do not teach students about sex or even at all, as far as I am aware, it’s doubtful that schools have taught children about these behaviors, thus these findings are independent of schooling.

Because of this, I believe it’s important that children learn comprehensive sex education at a young age since children aren’t oblivious to sexuality and sex, and teaching them about healthy relationships and sexual health can be beneficial for them, too.

To assume children aren’t curious about sexuality or know about sex is being ignorant of childhood sexuality. Since children engage and are curious about these behaviors, it’s beneficial to teach them about these things. “Childhood” is not as innocent as people would want it to be, and children can still be children — but we should not think this childhood is absent of anything sexual.