Racial Diversity and Social Capital: Quick Comments

It's more complicated than "Racial diversity isn't our strength", for God's sake!

In scrutinizing the complex relationship between racial diversity and social capital, this comprehensive review delves into the seminal work of Robert Putnam and subsequent studies that have shaped the discourse. The examination begins with Putnam's findings on the correlation between racial diversity and reduced levels of trust, subsequently navigating through methodological critiques and empirical analyses presented by scholars such as Baldassari, Abascal, and Williamson. This exploration traverses statistical nuances, challenges in measurement methodologies, and divergent perspectives on the practical implications of racial diversity on social capital. It underscores the need for a nuanced understanding, urging caution in interpreting studies that may not capture the intricate interplay between ethnicity, trust, and social dynamics.

When addressing the subject, one frequently referenced study is conducted by Robert Putnam. In his seminal work published in 2007, Putnam (2007) identified a correlation between racial diversity and reduced levels of trust towards individuals of other races and neighbors, as depicted in Figures 3 and 4. Subsequent interpretations of Putnam's research often assert statements such as "The study, acknowledged as the largest ever on civic engagement in America, revealed that nearly all indicators of civic health exhibit lower values in more diverse environments" (New York Times, 2007) and "In communities characterized by diversity, individuals are more susceptible to experiencing feelings of depression and withdrawal due to a perceived lack of connection with their peers" (Reddit, 2018). However, it is imperative to note that these second-hand assertions, while technically accurate, overlook the inclusion of Putnam's multivariate regression analysis.

As evident from the analysis, there exists a weak correlation between ethnic homogeneity and the prediction of trust in one's neighbors. As a sole variable, it accounts for less than 1% of the variance. These findings diverge from the exaggerated assertions propagated by second-hand interpretations of the paper. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that similar findings have been replicated in other geographical regions, as exemplified by research conducted in Europe, such as the work by Baldassari and Abascal (2017: 726-727).

There are good reasons to cast doubt on these studies, as Baldassari and Abascal remark. Baldassari and Abascal observe that studies in this domain typically employ three methodological approaches. Firstly, they utilize indexes of heterogeneity, which gauge the likelihood of two randomly selected individuals belonging to the same racial or ethnic group. However, these indexes fall short in accounting for variations in ethno-racial composition, and they are categorized as ecological analyses. The commonly applied indexes in these studies inadequately capture the nuanced racial composition within an area. Secondly, they fail to account for the historical and contextual aspects of the ethnic cleavage present in the region, and they lack consideration for out-group contact. Additionally, these ecological analyses neglect to adjust for confounding variables between racially diverse areas and homogenous areas. In Putnam's paper, these distinctions are acknowledged by the authors (pg. 734).

Crucially, the assessments of trust in studies such as Putnam's may not necessarily be indicative of what commentators of the paper presume it to measure, namely trust in the real-world context. As underscored by the authors, "There is evidence suggesting that attitudinal measures of trust do not reliably predict actual trusting behavior in real-world or experimental settings (Glaeser et al., 2000; Karlan, 2005; Sapienza, Toldra-Simats, and Zingales, 2013)" (729). Additionally, it is noteworthy that individuals from non-white backgrounds tend to exhibit lower levels of trust compared to their white counterparts in a general sense.

When utilizing the same dataset employed by Putnam, the authors highlight that the data set was not chosen through random selection. Instead, certain groups were deliberately oversampled or excluded, and decisions were made regarding which areas were to be investigated and the quantity of surveys conducted. Furthermore, the linear regressions conducted by Putnam (Fig. 3, Fig. 4) may not necessarily be examining the relationship between racial diversity and trust; rather, they may be scrutinizing the sorting of racial groups with pre-existing levels of trust. These figures merely indicate the existence of a relationship but offer limited insights into the causal mechanisms governing such relationships. In their efforts to replicate Putnam's findings using the same dataset and employing more appropriate measures of heterogeneity, the authors did not achieve replication once additional variables measuring ethnoracial differences between respondents and their communities were taken into account.

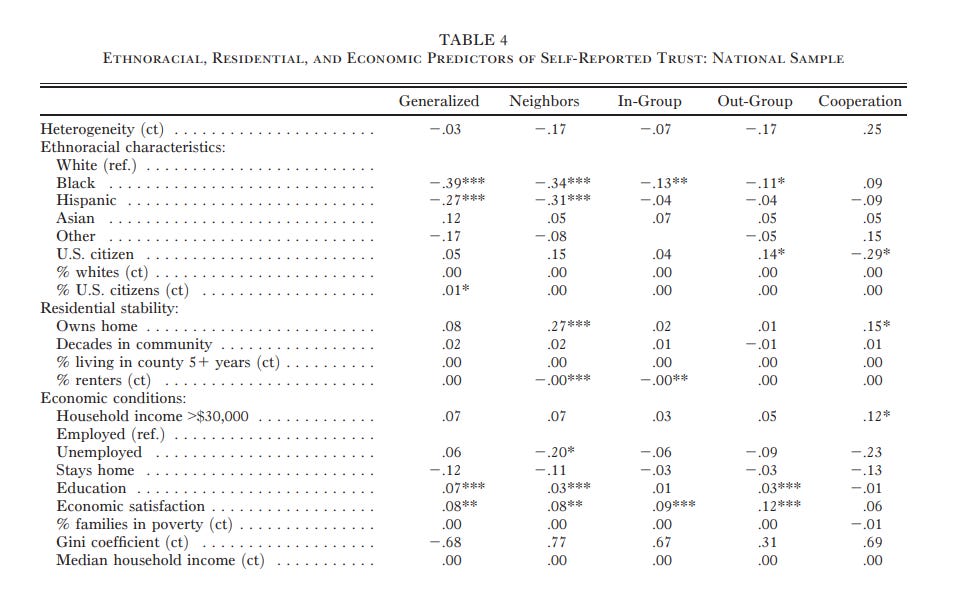

The effect sizes significantly decrease once further adjustments are made. This shows that heterogeneity had largely weak and statistically insignificant effects on multiple domains of trust (trust in neighbors, in-group, out-group, and cooperation [The actual racial differences in trust are minimal, surprisingly. There is not even a full-point difference between racial groups (see pg. 740)].

In their analysis, which used repeated random samples and further controls, there was no relationship across any social capital domains.

Caution is warranted when interpreting studies such as Putnam's and others, considering the methodological assumptions involved. It is noteworthy that the measurement employed for racial diversity did not demonstrate predictive capability across various domains of social capital. From a statistical standpoint, the absence of statistical significance suggests no discernible effect; however, there is an effect in the proposed direction. Nevertheless, the tenuous nature of these relationships may suggest that the practical impact of racial diversity might not be as pronounced as commonly assumed.

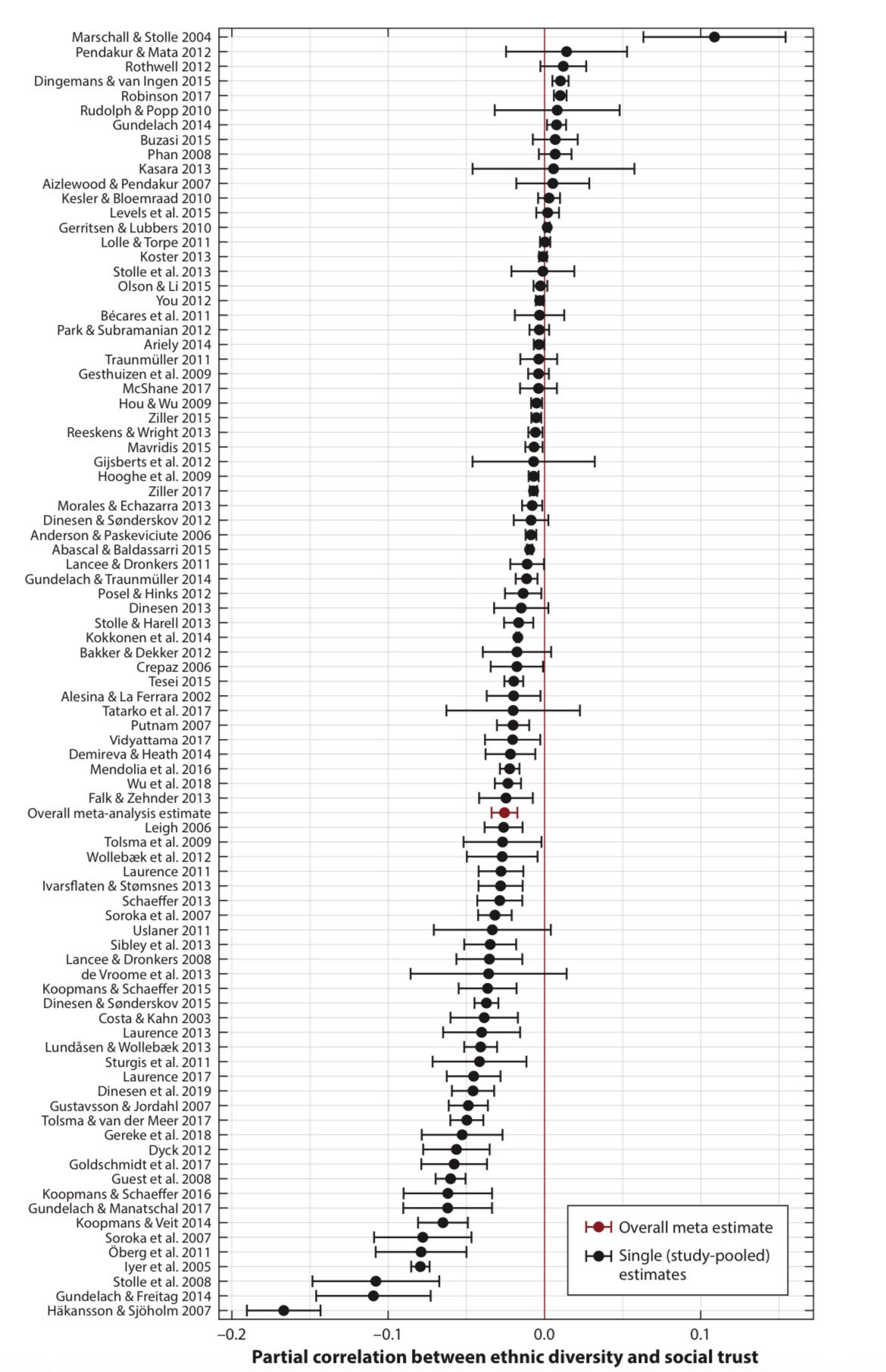

Indeed, other analyses have shown a weak-moderate -practical relationship between ethnic diversity and social capital. In a meta-analysis of 87 studies, the relationship between racial diversity and social capital was statistically significant, but practically weak at -0.025 (Dinese, Schaeffer, and Sønderskov, 2020). In other words, ethnic diversity could not explain at least 1% of the variance in social capital.

Koopman and Schaeffer (2016) found a relationship of -0.09, with the effect being reduced to -0.052 with further adjustments. In Dinese, Schaeffer, and Sønderskov;s analysis, the effects of racial diversity on different types of trust never reached higher than -0.04. Alesina and La Ferrara (2005) found racial diversity, but not ethnic diversity, to negatively correlate at -0.238. Looking at 3 measures of social capital, Guest, Kubrin, and Cover (2006) found 1% of the variance was explained by racial diversity.

One’s pre-existing views on racial minorities can also impact the relationship, as people who already perceive out-groups as threatening experience reductions in neighborhood trust — and longitudinally, as one’s views on racial minorities change, so does their levels of trust (Lawrence, Schmid, and Hewstone, 2018). Indeed, individuals who talk to their neighbors are less influenced by racial and ethnic characteristics than those who do not speak to their neighbors (Stoelle, Soroka, and Johnston, 2008). Real-world changes where non-whites come in flux to a different large white majority area have also not shown changes in social capital. This was found in Maine when using Australia as a control group (Williamson, 2008).

In conclusion, the discourse surrounding racial diversity's impact on social capital unfolds as a nuanced interplay of methodological considerations, statistical intricacies, and contextual factors. The review traverses a spectrum of studies, ranging from Putnam's influential work to subsequent analyses that question the robustness of the observed correlations. Importantly, it highlights the weak and sometimes statistically insignificant effects of racial diversity on multiple domains of trust and social capital. The meta-analysis and empirical studies discussed offer a textured perspective, revealing a complex relationship that resists simplistic interpretations. As one navigates through the varied findings, it becomes evident that the practical implications of racial diversity on social capital may be less pronounced than initially assumed, calling for a more nuanced and contextualized understanding of these intricate dynamics.