Politics and Mental Health

Liberals tend to have lower mental health than conservatives, but why?

If you spend enough time in political circles, whether it be left-wing ones or right-wing ones, sometimes it’s said that people on the opposite political spectrum are mentally ill. This could be like conservatives saying liberals are mentally ill, or socialists saying right-wingers are mentally ill, for example. As I say here, those on the left do tend to be mentally ill at a higher rate than those on the right, and possible explanations for this are discussed.

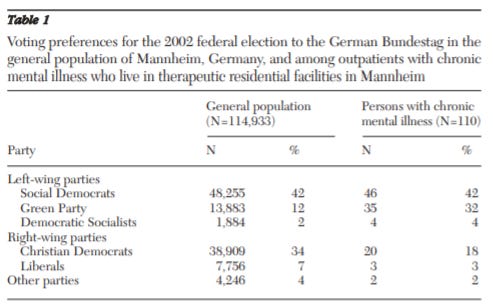

Looking at 110 patients with mental health issues living in therapeutic residential facilities in Germany, Bullenkamp and Voges (2004) measured the patient’s voting preferences and found that they were more likely to vote for left-wing parties than right-wing parties in Germany.

Duckworth et al. (1994) examined 165 subjects from a mental health service center and administered them a 12-item test to measure their voter preference. Of the 91 voters who did vote among the 165 subjects, 31.9% voted for George Bush, 61.5% voted for Bill Clinton and the remaining 6.6% voted for someone else. Thus, those with mental illness in this study were more likely to vote Democrat than Republican, and the effect was not affected by age or sex.

Ron Guhname (2007) on The Inductivist looked at data from the General Social Survey and did a cross-tabulation between political orientation and the history of mental illness. He found that liberals were more likely to report having a mental illness than conservatives, even on the more extreme ends of liberal and conservative.

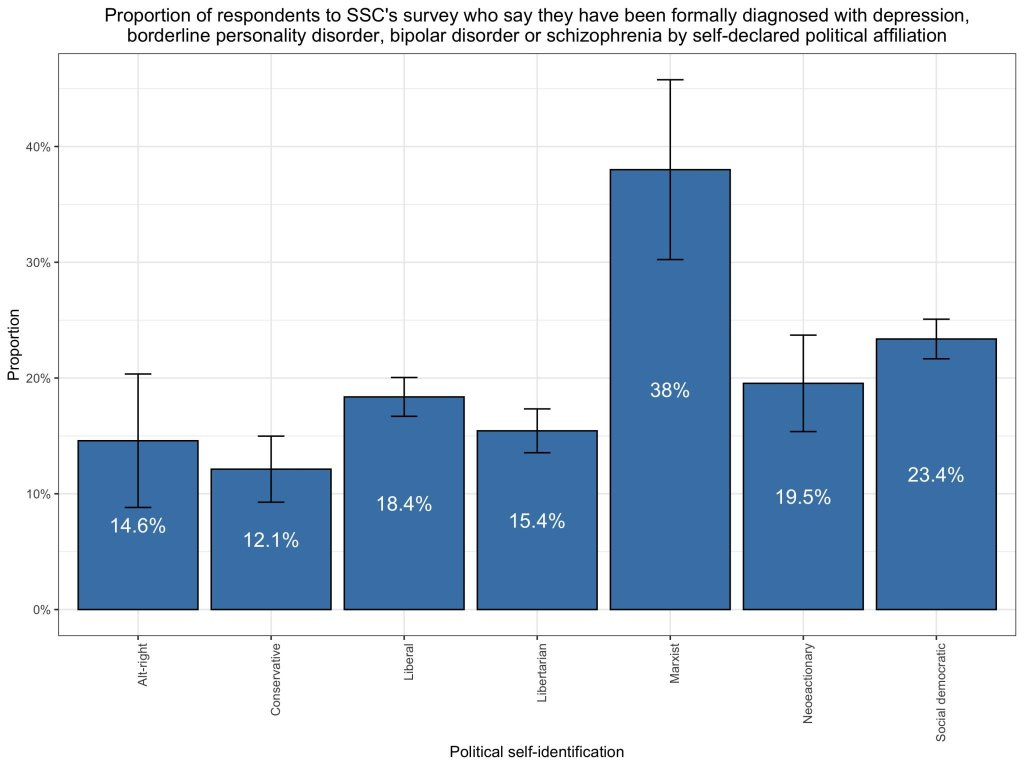

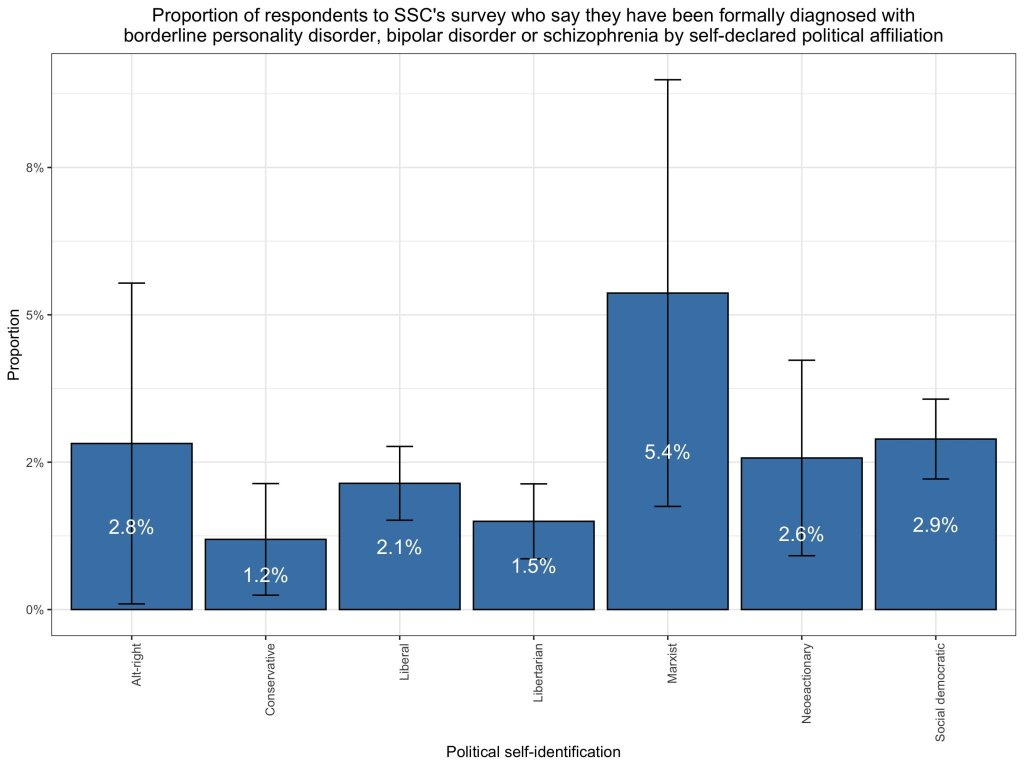

Using data from a survey conducted by Alexander (2020a), Phillipe Lemoine made bar graphs that show that those on the left are more likely to report mental health issues than those on the right, except in the case of having been diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia where the alt-right scored higher than social democrats (2020).

Of course, though, Alexander (2020b) notes that the findings could be unrepresentative since his readers may not reflect the average right-wing person or left-wing person, along with other issues. However, data from Guhname uses GSS data, which is based on a random sample of people so its representative data shows similar results as Lemoine’s table (with the exclusion of more political ideologies rather than liberal and conservative).

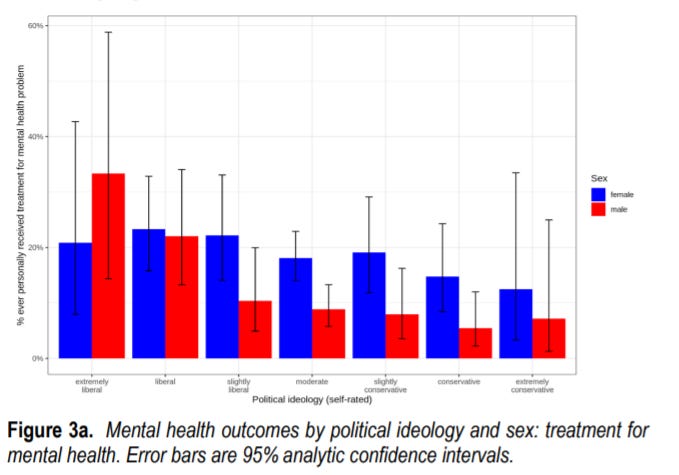

Also using GSS data, Kirkeegard (2020) examined GSS data from 1972 to 2018 and found that liberals were more likely to tend to report being treated for mental health issues, ever having had had mental health issues, counseling in the past year, more days of poor mental health, and emotional/ mental disability.

The large error bars show that there is a lot of variability in the data for some groups, and less so for others. Regardless, the results held even after controlling for age and sex among the sample, liberals reported lower happiness and life satisfaction than conservatives, and mental illness was higher among liberals after conducting a meta-analysis, according to the paper. Clearly there is a trend.

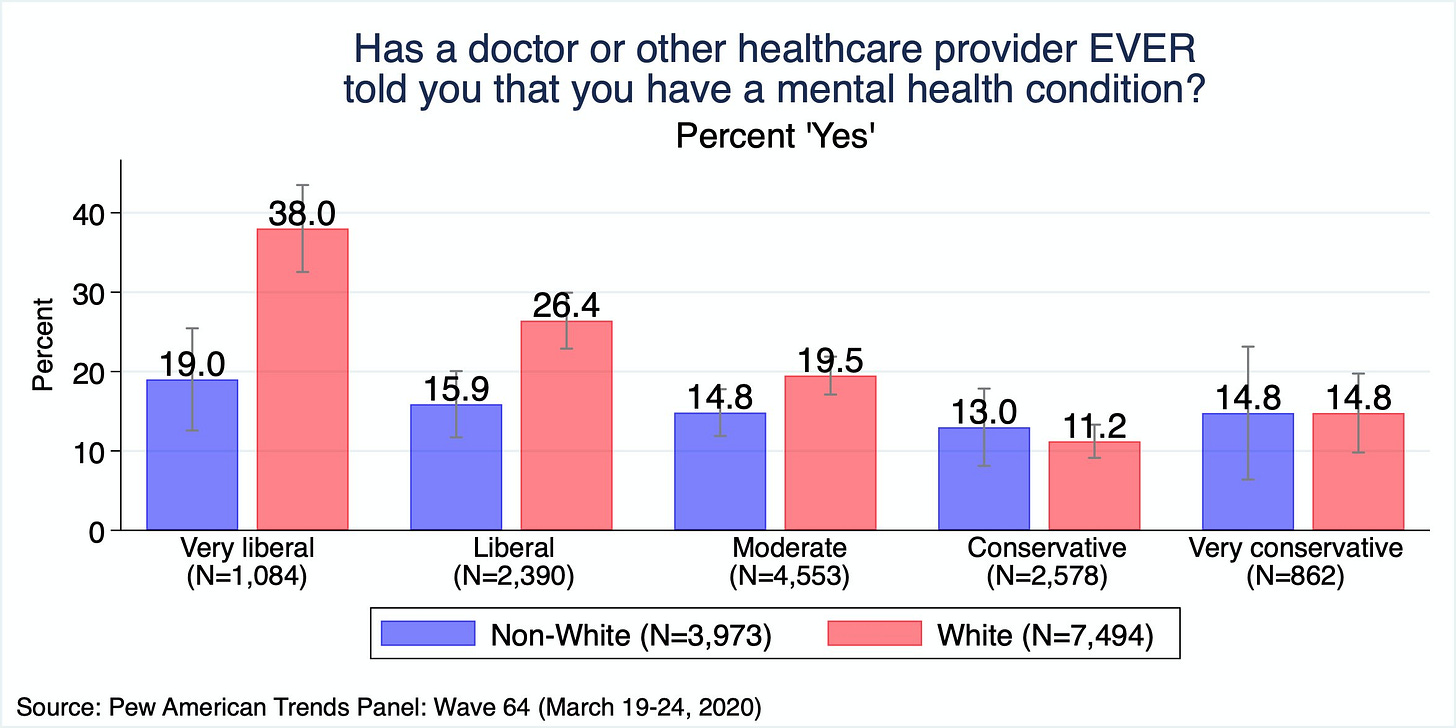

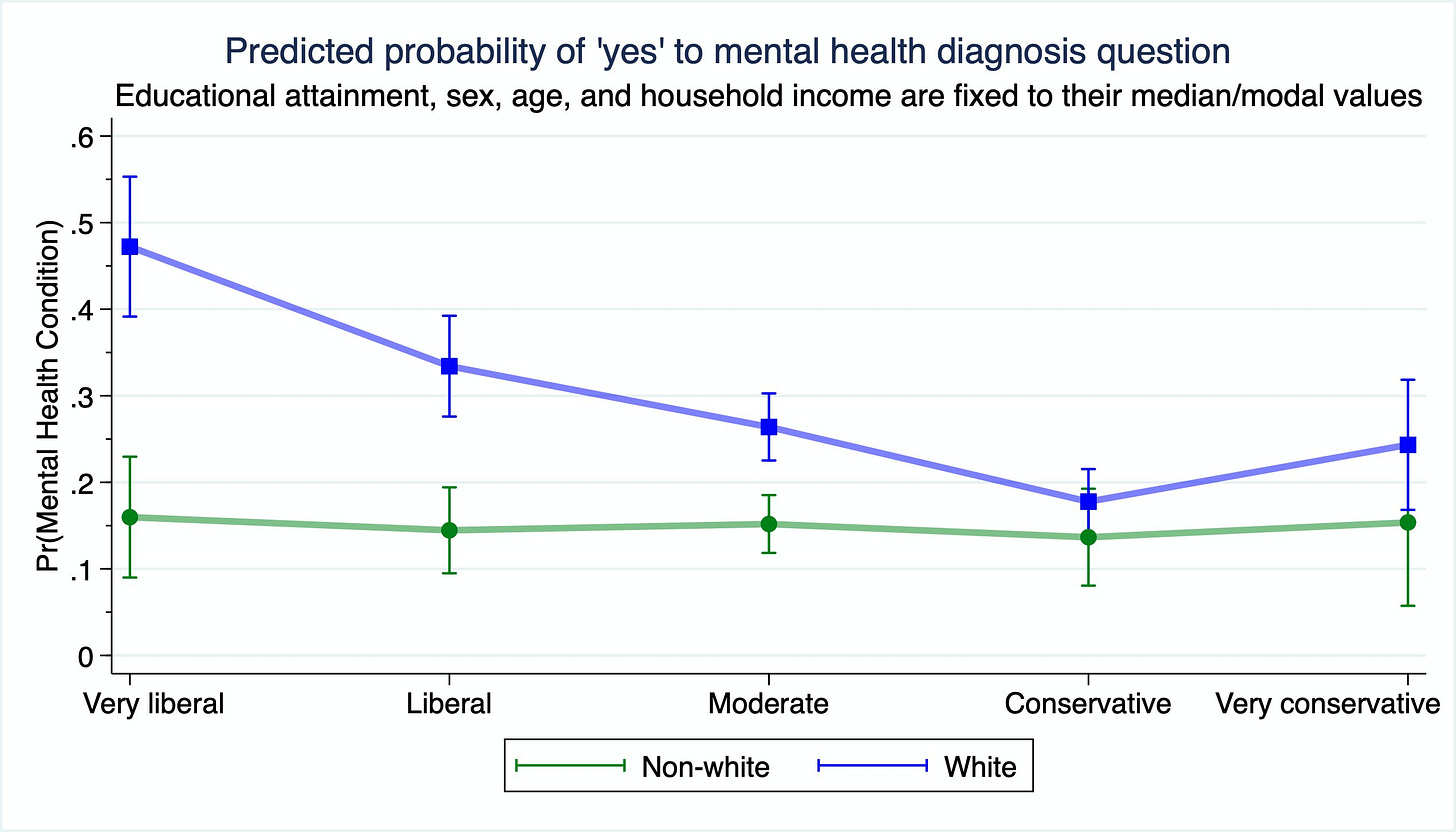

Zach Goldberg used data from PEW during COVID and found similar results as Kirkeegard. Those on the left were more likely to report ever being diagnosed with a mental health condition than those on the right.

The difference remained even after adjusting for educational attainment, age, and household income.

Those on the left were also more likely to report lower mental health in the past 7 days, but the difference during COVID could partially be explained by prior mental health during COVID.

Although the data shows that liberals are more likely to be mentally ill than conservatives, why is this? One plausible idea would be that personality predicts political orientation. In other words, depressed individuals are more likely to go to the left than to the right. Hatemi and Verhulst (2015), however, found that political attitudes develop independently of personality traits, casting doubt on personality and leading to political attitudes.

Instead, personality traits measured at one time did not correspond with a change in political attitudes, so it’s unlikely that personality can lead to political attitudes. This was also the finding in Verhulst, Eaves, and Hatemi (2012) who found no causal relationship between personality and political ideologies.

Another possible explanation might be that of religion. As has been shown in the literature, religious people tend to be happier than non-religious individuals. VanderWheele (2017) found that religious communities were associated with “human flourishing.” This includes things like happiness and life satisfaction, mental and physical health, meaning and purpose, character and virtue, and close social relationships. Chen and VanderWeele (2018) looked at 5,000 adolescents and followed them for 8 years. In this study, they controlled as many confounding variables as they could to try and isolate the effect of religion. They found that those who were raised in religious or spiritual environments were 18% more likely to report higher happiness.

Since those on the right tend to be more religious than those on the left, religion acts as a protective buffer in some sense and could lead to higher happiness among the right than the left. However, this is assuming a causal relationship in which adopting religion may lead to higher happiness, but does seeking the divine really lead to this?

Summarizing lines of data, Pohls (2021) notes that the relationship between religiosity and mental health is non-linear, meaning that those with weaker religious beliefs were less well than those with stronger religious beliefs. One 2011 study also found that religion might not be beneficial for everyone and that those who leave religion would be better off. A 2012 study also found that most religious individuals had higher levels of life evaluation, but non-religious people had reported higher levels of life evaluation than moderately religious people. Context also influences the results, with some places like Canada, Denmark, and the Netherlands showing no relationship between religiosity and life satisfaction. Once further variables are adjusted the difference between the religious and non-religious levels of life satisfaction goes away.

Lim and Putnam (2010) found that religious people are happier because of the social networks they build in church, not because of the divine. Thus, simply going to church doesn’t matter, but having lots of friends at church does to the correlation between religiosity and happiness.

However, social groups at church cannot fully explain why religious people are happier, as the pseudo-R-squared here was 6%. This means that while religion might be able to explain some of the variance in political ideology differences in mental health, it cannot explain the entire thing.

Another explanation for the correlation between political ideology and mental health can be the stigma surrounding going to the doctor, as hinted by Alexander.

Looking at 518 people, DeLuca et al. (2018) found that among right-wing authoritarians, right-wing authoritarianism was associated with a stigma against mental health, even after adjusting for like education, age, social desirability, race/ethnicity, gender, geographic location, and prior contact with mental illness

DeLuca and Yanos (2015) also found that right-wing authoritarianism and political conservativism are associated with stigma toward mental health. Conservatives also reported higher levels of stigma towards mental health.

Because of this, it’s likely that those on the right are less likely to seek out help for mental health issues or be less likely to be honest when reporting their mental health issues when asked. Although there is no shame in having mental health issues, these issues could lead to lower-bound estimates when it comes to measuring political ideology and mental health.

Of course, though, stigma may not be the sole explainer of this. As Goldberg found, liberals are more likely to score higher on neuroticism and lower on happiness and life satisfaction, some of these differences could be genuine. One explanation I’ve heard for these results is that those on the left know what’s wrong with the world and thus it could lead to lower mental health, but I have been unable to find any data on if this could be a variable or not, or just a scapegoat for pre-existing issues.

In conclusion, although those on the left tend to report higher mental health issues than those on the right, this could be due to the stigma surrounding mental health among those on the right, leading to being less likely to report being mentally unhealthy and seeking help, and a genuine difference. It’s doubtful these variables explain 100% of the variance, so denying a genuine difference is unwarranted. Although possible mediating variables like religion and personality could explain why those on the left tend to report high mental health issues, it seems like they fail to do so under empirical scrutiny because of their non-causal relationship.

Hey Francis are you the author of the Vaush research doc rebuttal? I was hoping you could look at this garbage and rebuff it as well: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1-iaG91cE0vT-21OPV0kZPu7lN3PsPtMs8yvobjtov64/mobilebasic