On Traditionalism

Comments on different aspects of traditionalism and their effects on relationships, like gender roles, housewives, children, and pre-marital sex

Among some right-wing circles, there is a subset of individuals who seek to “return to tradition”, with them encouraging other individuals to have kids, be in marriages with traditional gender roles, don’t have premarital sex, and have women be housewives. When taken at face value, this seems like something that might work, but under empirical scrutiny, this doesn’t seem to be the case.

Before the issues with traditionalism can be discussed, comments have to be made about the way in which those on the right fetishize traditionalism, specifically traditional families. Based on observation, it seems that traditional families are fetishized because of how bliss they were portrayed in media and promotional art. For example, take the show Leave it to Beaver, a classic American showed with portrayed a traditional family living in late-1950s America. You had a mother, father, and their children living in the suburbs with a nice home, but this was not how life actually was for the average family at the time. As Coontz (1992) notes in The Way We Never Were, 25% of families in the mid-1950s were poor, and women who did not fit the domestic roles their husbands made were labeled as neurotic, perverted, or even schizophrenic and were given shock therapy to fix these issues. Issues of child abuse, sexual abuse, and physical abuse were also issues. As Coontz notes when talking about physical abuse towards wives,

Psychiatrists in the 1950s, following Helene Deutsch, “regarded the battered woman as a masochist who provoked her husband into beating her.”

Data on partner abuse in the 1950s and around that time is hard to come by since partner violence was not considered a police matter, but rather a family matter (Johnson 2002). Because of this, it’s hard to know how prevalent partner violence even was, but based on the anecdotal evidence we do have, it seems like things weren’t all apple pie and peaches for some housewives in America. Pleck (2004) notes how during patient counseling in the 1950s for the Family Service Association, one patient, who was called Mrs. K, came to the association because her husband sexually and physically abused her multiple times due to his alcoholism. However, instead of the association blaming the husband’s alcoholic rage, they blamed Mrs. K because she refused sex with her husband when he would come home at night from his night shifts at work. The association said that Mrs. K needed therapy, not because of her husband, but because of her “anxieties about sex activities.” More is discussed in Coontz, so a discussion on the issue of abuse would end here.

Regardless, the idea of the traditional family is shaped by how the media portrayed it: a happy, loving family where the husband is the breadwinner and the wife is the caretaker. As has been noted by Coontz and will be discussed below, this idea of the traditional family being happy as they were portrayed in media and illustrations is largely a myth. This fetishization of the traditional family, while understandable, is based on an idea that didn’t really exist to such a prevalent degree as traditionalists think of it.

Traditional and Egalitarian Marriages

Starting in the 1960s, researchers analyzed how egalitarian marriages faired out when compared to traditional marriages, with the former being defined as a relationship with little to no gender roles and the latter one with gender roles. For example, an egalitarian marriage might consist of role-sharing and equal power in the relationship, while a traditional one would consider the man being the one with the most power in the relationship and the wife staying home and doing house chores. During the first wave of these studies, the majority of them found that egalitarian relationships did better than traditional ones.

Locke and Karlsson (1952) looked at 929 people from Indiana who were happily married and divorced individuals, and 423 people who were from Sweden who were almost entirely husbands and wives. When looking at predictors of marital adjustment, it was found that one spouse not having more power than the other was predictive of marital adjustment for both the Indiana sample and Swedish sample.

Equality in taking the lead, in which one spouse doesn’t have more power than the other one, was associated with better marital adjustment. Thus, equality, or the absence of one single dominant party in the relationship, was positively associated with marital adjustment.

Blood and Wolfe (1960) looked at 909 families and found that those in egalitarian marriages were happier than those in traditional relationships, but I have been unable to find a pdf of the book online.

Centers, Raven, and Rodrigues (1971) looked at 747 respondents (410 were wives, 337 were husbands) through person-to-person interviews. Their views on different questions relating to who makes decisions were measured and so was their personality. It was found that couples that made mutual decisions were happier than those who didn’t, showing that individuals benefitted when both had equal power in decision making rather than one having most or all the power.

Bean, Curtis, and Marcum (1977) looked at 325 Mexican American couples from the 1969 Austin Family Survey. For both husbands and wives, two measures of marital satisfaction were derived from 4 items patterned from a previous study. The responses led to 5 decision making categories: (1) Joint (3/5 decisions were mutually made); (2) Husband dominant (3/5 decisions were made by the husband); (3) Wife dominant (3/5 decisions were made by the wife); (4) Husband and wife (2 decisions made by both parties); (5) Unpatterned (consists of all other combinations).

For both husbands and wives, being in a relationship where there was either joint power, both husband and wife, or unpatterned was associated with higher marital satisfaction. Those in relationships where the wife or husband was dominant in their conjugal power scored lower than those in more egalitarian relationships.

Although earlier studies showed egalitarian relationships to have higher marital satisfaction than traditional relationships, these results changed around the late 1970s to 1980s, with traditional relationships being better than egalitarian ones—but with some caveats in gender differences.

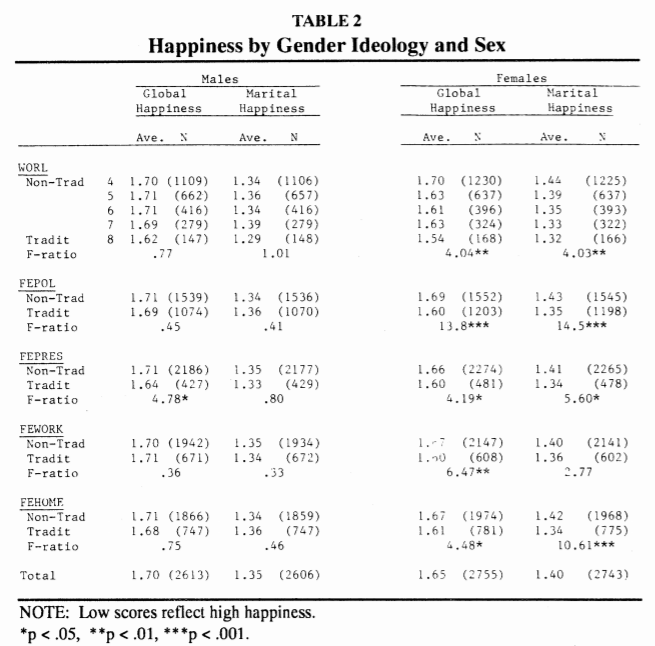

Lueptow, Guss, and Hyden (1989) looked at General Social Survey data spanning between 1972-1986. Their views on traditionalism were measured through these questions:

Of women who held non-traditional attitudes, they were less happy and remained married despite the stress associated with their views on gender roles. Traditional women were happier and less likely to divorce.

However, this effect was only true for women and not men. Men saw no relationship between their views on gender role ideology and their happiness, suggesting that traditionalism might benefit women and not men.

For women, the relationship is held even after adjusting for age, year, education, and work status. Similar findings with discordant effects between genders was also found in other studies, too.

Amato & Booth (1995) looked at 1,592 married people and looked at their perceived marital quality. Using a seven scale item, respondents were asked if they strongly agreed, agreed, strongly disagreed, or disagreed with statements reflecting men and women’s work/ family roles: (1) a woman’s most important task in life is being a mother; (2) a husband should earn a larger salary than his wife; (3) a husband should share equally in household chores if his wife works full time; and (4) a woman should not be employed if her husband can support her.

In table 1 of their study, it showed that as wives adopted egalitarian views on marriage their perceived marital quality decreased. For husbands, though, their perceived marital quality increased as they adopted egalitarian views. As wives adopt non-traditional views on marriage, it led to a decline in marital quality, less interaction, more disagreements and problems, and a higher proneness. Nontraditional attitudes were positively associated with the divorce rate between 1980 and 1988, and women would also adopt feminist views after a divorce. Changes in marital quality didn’t affect the gender-role attitudes of husbands or wives. Wives with traditional values faired out better than those with egalitarian values, but the same was not seen in the male sample.

Using data from the National Survey of Family and Household, Wilcox and Nox (2006) analyzed data from 5,010 people and measured how these different variables affected wives’ happiness and husbands’ affection and understanding. It was found that when both the husband and wife had egalitarian gender roles, wives were less likely to be happy and men were less likely to be affectionate and understanding. A wife working full-time and part-time was negatively correlated with happiness, and so was when a wife earned most of the income than the husband.

However, caution should be taken when using this study as in model 3, the adjusted R^2 is 0.15, showing a good fit model, but just barely. Furthermore, egalitarian gender roles for both men and women had weak coefficients and were not statistically significant. Lack of statistical significance was also found when a wife earns 66% of the couple's income, and the same was true when a husband earned 66% of the couple’s income. This suggests that these variables associated with traditionalism and egalitarianism were weakly correlated with wifes’ happiness and husbands’ compassion and understanding.

Of course, from the top studies, it seems like traditionalism is positive for relationships, but this relationship only holds when discussing how it affects women. When men are analyzed, like in Amato and Booth, men aren’t positively affected by egalitarianism. Indeed, other studies have also suggested this to be the case.

Data from the 1994 Iowa Youth and Families Project panel found that men who held egalitarian attitudes towards gender roles reported higher levels of happiness than those with traditional views (Kaufman and Taniguchi 2006).

Egalitarian attitudes were positively associated with reporting being in a very happy relationship, and the spouse’s egalitarian attitudes were also associated with higher happiness in the relationship, but this effect was not statistically significant. When the difference in happiness between men with egalitarian and traditional views on gender roles is translated into Hedge’s g, the difference is 0.24, a small difference. For women, however, the difference between women with egalitarian and traditional views on gender roles was trivial at 0.19.

This was also the finding in Perry-Jenkins and Crouter (1990). In this study, it was found that husbands who held traditional views on gender roles (main/ secondary providers) scored lower on marital satisfaction than those in the co-provider category, which was the egalitarian one.

The sample is small but fits in line with the Kaufman study. A similar study by Vannoy and Phlliber (1992) found that, among their sample of 452 people, husbands’ views on gender roles were negatively correlated with marital quality when their wife was a working woman.

Kaufman (2000) found that in the National Survey of Family Households, egalitarian men were less likely to be divorced, or single, and were more likely to be married than traditional men.

For women, traditional women tended to fair out better than egalitarian ones, a finding noted above. In the author’s logistic regression, holding egalitarian attitudes increased the chances of entering a cohabitation union, and were less likely to divorce or separate for men. Attitudes had no effect on the decision to marry or separate.

Contrary to these studies, Forste and Fox (2012) found that traditional men had higher family satisfaction than egalitarian men.

Surely, this does suggest that maybe both men and women benefit from traditionalism rather than only women. However, when looking at the coefficients produced by gender roles, we find no large effects, but they are statistically significant but just very weak.

In model 5, join-decision making is positively associated with family satisfaction at a statistically significant level, men doing a larger share was significant but small, and traditional gender roles and the nuclear family were weak but statistically significant. The R^2 for this study was .08, which shows lots of measurement error in the way social scientists are measuring these things and shows a poor fit model. Not the best study, and it does not suggest that traditional roles are higher for family satisfaction. The study also does not provide us with means and standard deviations to calculate a difference in marital satisfaction.

In conclusion, it seems that when it comes to traditional relationships, women benefit but not men. Men better benefit from egalitarian attitudes in gender roles rather than women. To the traditionalists, they might take these negative effects if it means that their wives are happy, but what’s the point in staying in a relationship in which only one person is happy and the other isn’t for the sake of traditionalism? Furthermore, in modern times, finding a traditional woman might be difficult since most people believe in role-sharing rather than strict gender roles in relationships.

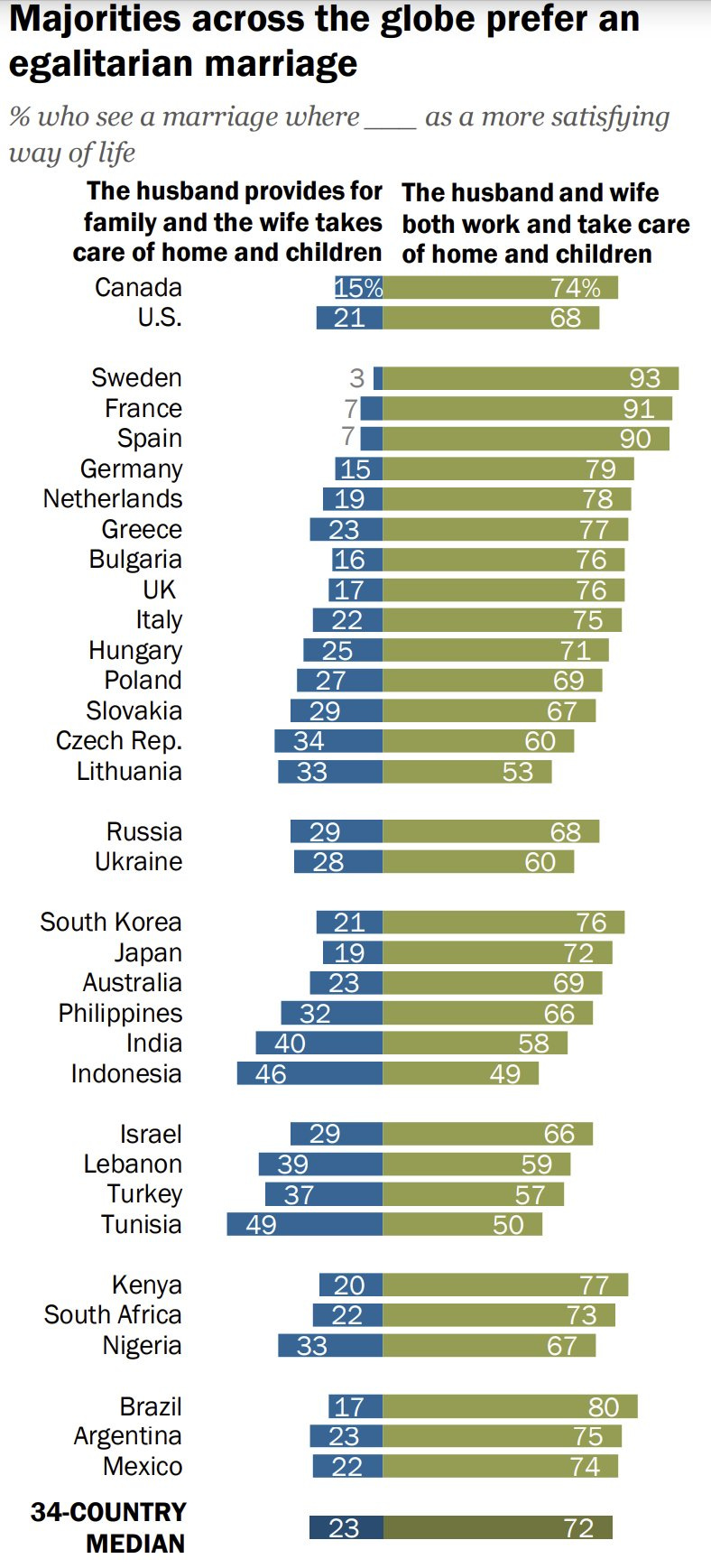

In a recent PEW survey, 72% of people across 34 nations said that when a marriage had both the husband and wife working and both taking care of the kids, it was a more satisfying marriage than when just the husband provides for the family and the wife takes care of the kids (Horowitz and Fetterolf 2020).

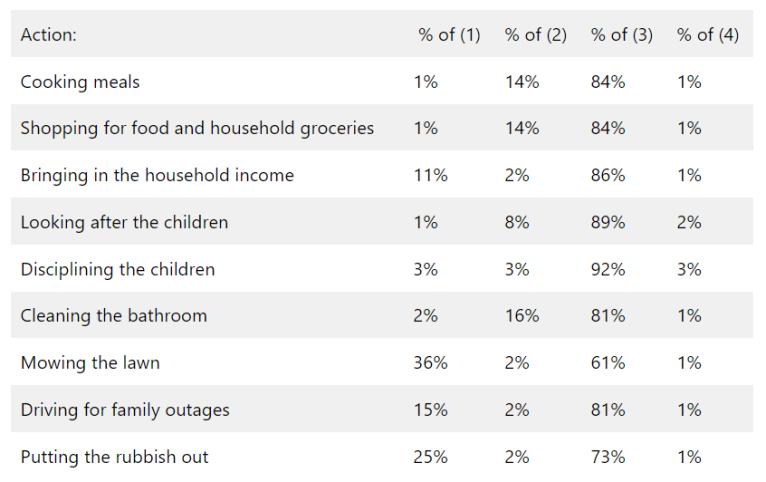

Looking at 60,000 people in New Zealand who were asked the question: “Who do you think should be mainly responsible for the following in families with children?” and who were given the choices of (1) The boys and men in the home; (2) The girls & women in a home; (3) All genders in a home; (4) Don’t know.

It seems in modern times, role-sharing is preferred rather than classic gender roles prescribed by traditionalists talking points. This was also hinted in by an older study looking at the effects of role-sharing on relationships.

Haas (1980) looked at 31 role-sharing couples (the great majority were later found out to be egalitarian) and gave them open-ended questions. Almost all the couples in the sample reported that they took on a role-sharing marriage not because they were ideologically committed to sexual equality, but rather because it was a practical way of obtaining benefits that they perceived could not be achieved in a traditional marriage with segregated husband-wife roles. The benefits hit the female first and then carried onto the male, but a considerable part of the motivation to try role-sharing roles was to free husbands from their confined traditional marriage roles. Many of couples adopted role-sharing roles so the wife could fulfill her desires outside of work. Women increased and almost reached the same time spent doing different activities as the men. The majority of the couples agreed that the men in the study decreased their feelings of the burden of having a provider, something attached to anxiety and stress. Of the benefits of role-sharing, people reported being better-married couples. Since decisions had to be made on a mutual basis, there was an increase in intimacy because of the communication between them. Another benefit was having more in common since both spouses worked and had domestic responsibilities. Role-sharing also gave couples more opportunities to do stuff together.

This was also hinted at in another study, too. Lye and Biblarz (1993) found that when couples/ partners shared an egalitarian attitude towards work and family, egalitarian women had higher levels of marital satisfaction and lower levels of marital conflict. Since shared egalitarian attitudes benefit women, and men benefit from egalitarian attitudes rather than traditional ones, it further suggests that role-sharing would be a healthy way to go in relationships rather than ones based on strict gender roles.

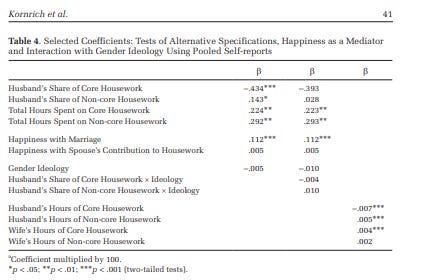

One of the more cited studies is Kornrich, Brines, and Leupp (2013), finding that couples with more traditional gender roles have more sex than egalitarian ones. However, the way this study is often presented doesn’t fit with what the study itself says. In describing this study, Venker (2019) titles her article “The happiest marriages are the more traditional ones.” This study suggests no such thing. The authors examined data from the National Survey of Family Households and found that couples in which the male did more non-core housework (work unrelated to house chores) reported lower sexual frequency than couples in which the male did more core housework.

The study did not measure happiness, instead measuring sexual frequency only. The standardized coefficients show a significant, moderate, and negative relationship between the share of core housework and sexual frequency. Gender ideology, which is a better measurement of one’s views on gender roles rather than who works where, shows no relationship between core and non-core housework and sexual frequency.

The interaction effects when looking at the share of core and non-core housework and ideology still show no effect, which matters since gender ideology is an arguably better measure of traditional gender roles than core and non-core housework. A more recent 2022 study found that an equal share of housework and mental load word increased sexual desire. Furthermore, Loewenstein et al. (2015) found that an increase in sexual frequency is not associated with an increase in self-reported happiness, showing no causal relationship between sexual frequency and happiness which has been found in correlational studies. This study does not support a traditional worldview.

In summary, traditional marriages only work for women and not for men, but egalitarianism works for both men and women when both partners share egalitarian attitudes. This is why egalitarian relationships make both people happy, but when there is a gender ideology imbalance, it only makes women happy and not men. Men are happier when they hold egalitarian values and when their wife also holds egalitarian views.

Masculinity and Relationships

Earlier studies showing traditionalism to be negative for both genders could partially be explained by the fact that masculinity seems to be negative for relationships, something which has not been discussed anywhere else, to knowledge. A hypothesis in this section is that more recent studies showing traditionalism to benefit women come from how they view gender roles in what people should do in relationships, but not masculinity itself which encompasses more than being a breadwinner.

One of the earliest studies that suggested this to be the case was published in 1978. Ickes and Barnes (1978) used the dyadic interaction paradigm (UDIP), a measure of empathic accuracy “as the extent to which a perceiver accurately infers a target person’s thoughts or feelings from a video recording of their spontaneous interaction together” (Vivian and Ickes 1990). The UDIP was used to examine initial interactions among matches dyad men and women in either traditional (masculine, feminine) or non-traditional (androgynous) gender role orientations. When masculine men were paired up with feminine women, their interactions were less rewarding and less involving than the non-traditional individuals who were paired up. The traditional individuals talked, looked, gestured, and smiled at each other less than the non-traditional individuals. In general, they did not like each other.

Of course, though, this study was on paired individuals and not couples, so its inferences can’t be made onto couples. Looking at a convenience sample of 2,100 female respondents who responded to a magazine survey in Ladies’ Home Journal, women in traditional relationships (the man is masculine and the female is feminine), based on the UDIP, were more likely to report higher feelings of stress, feeling fat, getting tired easily, feeling sad or depressed, feeling worthless, shy, and feeling that “you just can’t go on.” The non-traditional couple reported being happier because they had better communications, and had more optimism for the future (Shaver, Pullis, and Olds 1980, in Ickes 1985).

The findings of these older studies seem to fit in line with more recent studies measuring the effects of masculinity on relationships.

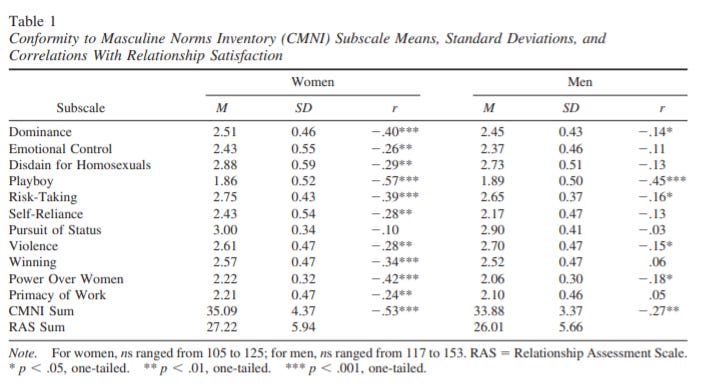

In a sample of 50 gays and 50 heterosexual men, Wade and Donis (2007) found that scoring higher on the Male Role Norms Inventory Traditional Scale was associated with lower relationship quality for both gay and heterosexual men. Those who did not score higher on traditional masculine norms had higher relationship quality.

Burn and Ward (2005) found that in their sample of 307 people, traditional masculinity was negatively correlated with relationship quality. Women who perceived their partner as high in masculinity reported lower relationship quality, and men who were higher in masculinity also reported lower relationship quality, too.

Rochlen et al. (2008) found that among 213 stay-at-home dads, scoring higher on masculinity norms was associated with lower well-being, lower satisfaction with life, and lower relationship assessment.

This is not to say that masculinity is bad overall, but rather that some aspects of traditional masculine roles taken too far can not only cause stress to the individual, but also to the relationship.

This hypothesis suggests that studies showing women to benefit from traditionalism partially do so because it has more to do with the male being the breadwinner, not with other aspects of masculinity that are associated with traditionalism.

Are Housewives Happier Than Working Women?

In the book The Feminine Mystique, Betty Friedan argues that, according to the evidence at the time, housewives were less happy when compared to working women (Friedan 1963). The issue with Friedan’s data is that most of it was based on non-probability samples. Looking at representative data between 1971 and 1976 from six national surveys, Wright (1978) remarked that there are no consistent, substantial, or statistically significant differences in happiness between housewives and working women.

When looking at the data, 6/14 tests (42%) surveys revealed that working women are happier than housewives. In the remaining 8 surveys, though, housewives were happier than working women. In 1976 when working women were happier, even the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (p > 0.10). Just like Wright, Campbell et al. (1976) also found similar results as noted up above. In re-looking at Wright’s data, Ferre (1984) found that working women score higher on intrinsic rewards than do full-time housewives of the same class; housewives also scored higher than working women on ease of life, but these differences are significant for only middle-class women.

Benin and Nienstedt (1985) utilized GSS data from 1978, 1980, 1982, and 1983 which were then combined. After looking at the data, there were no striking differences between housewives and working women in terms of their happiness, as noted in Table 1 below:

Drawing from cross-national data from 28 countries, Treas et al. (2011) found a small but statistically significant happiness advantage in favor of housewives. This advantage held even after controlling for family life variables. Blanchflower and Oswald (1998) found that self-employed wives are happier than housewives, but another study found that wives who work part-time are happier than those who work full-time or those who decide to be housewives (Booth and van Ours, 2008; 2009; 2010). More recently, it was found that there are no significant differences in subjective well-being between homemakers and part-time workers, and that homemaking was positively associated with happiness among those who left high-quality employment for childcare, according to data from European countries (Hamplova 2019).

Beja Jr. (2014) used data from the World Values Survey that spanned people in the ages of 18 to 70, and they found that working wives reported higher rates of life satisfaction than housewives. Housewives were happier than working women but only in middle-income economies. When looking at low-income and high-income economies, there was no difference. After controlling for socio-economic profiles and occupational status, there is no difference in life satisfaction between working wives and housewives. According to the author, “results show that a housewife, a part-time working wife, or a self-employed wife is not significantly happier than a full-time working wife at the 0.05 significance level. If a 0.10 significance level is acceptable, then a housewife appears to be less happy than a full-time working wife (p=0.07).” Similar results were also found in Beja (2012).

Okulicz-Kozaryn and Valente (2017) looked at GSS data spanning 1972 to 2014 and examined the life satisfaction of working women and housewives. Until recently, women were happier to be housewives or to work part-time than full time. This especially held for women who were older, married, with children, in the middle or upper class, and living in suburbs or smaller places.

Interestingly enough, there were sex differences in the correlation between hours worked and subjective well-being.

As can be seen, men who worked longer hours have higher subjective well-being than men who worked shorter hours. When looking at women, the results were reversed. Those who worked fewer hours had higher subjective well-being than those who worked more hours, and this held even after correcting for predictors of happiness. They also found that housewifery is associated with more happiness for women who are married, have children, who are middle class or upper class, and who are living in suburbs or smaller places.

Moving onto other areas of well-being, data from 2,440 U.S. adults (21+) showed that employed wives have lower distress scores than homemakers, and a wife’s employment is associated with higher distress for their husband (Kessler and McRae, 1982). When it comes to mental illness, housewives are more likely to report symptoms of mental illness (see Gove and Geerken, 1977), but later analysis showed this not to be the case (Phyllis, Myrna, and Myers, 1979). Working women, though, took more satisfaction from their outside job than housewives did from them working at home. A major con to being a housewife is the reduced income (Stickney and Konrad, 2007). When asking if housewives are happier than non-housewives of equal family income, only small effects are found. Making a full income per year outweighs the psychological benefit of being a housewife. Women working in the real world have higher female psychological well beings, a finding from Okulicz-Kozaryn and Valente (2018) who used General Social Survey data.

In conclusion, being a housewife doesn’t seem to make women happier than if they were to work. Most of the differences are statistically insignificant, and even then being a housewife is only good for specific women with certain characteristics. An important population to focus on for this issue is children. More specifically, how are children affected by working mothers and stay-at-home moms?

In an early review of the literature, Scarr, Phillips, and McCartney (1989) found that maternal employment had no effect on child development, daughters often ended up with better grades and better confidence, and that “social achievement, IQ test scores, and emotional and social development are every bit as good as that of children whose mothers do not work.” That maternal employment has no effect on child development was also noted in Kamerman and Hayes (1982). Thus, maternal employment doesn’t seem to have an effect on children, but this only holds true for non-infants. Working takes time away from infants (Kim 2013), but this issue could be mediated by having maternal leave policies in place.

Children and Happiness

One aspect of traditionalism is that when married, people should have children. It’s important to note the effects have on a relationship when people actually do have kids together.

White et al. (1986) looked at 1,535 married individuals and found a statistically significant, negative correlation between children and marital happiness (r = -0.11, p < .01 ). The presence of children brought lower marital interaction, more dissatisfaction with finances and the division of labor, and more traditionalism of the division of labor.

The negative correlation between children and marital happiness was partially spurious. It wasn’t children in general who were problematic, but rather specific children. White (1983) looked at 2,034 married men and women through 55-minute interviews.

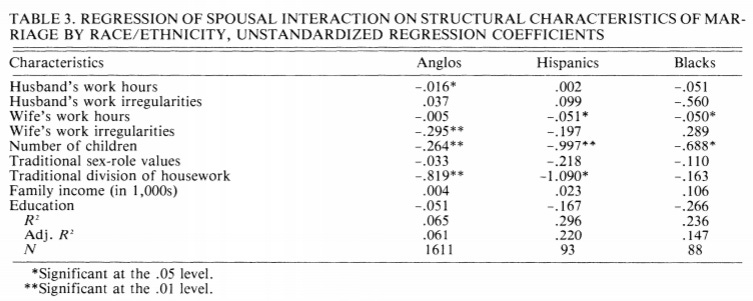

The number of children was negatively correlated with spousal interaction. When broken down by race, the negative effects of children were stronger for nonwhites than for whites.

So, although the number of children a couple has led to lower spousal interaction for all races, it’s stronger for other races than whites but the negative effects are still found in all races.

Zuo (1992) looked at 1,278 from a national sample of married individuals. When looking at predictors of marital satisfaction, Zuo controlled for variables like work hours, work irregularities, presence of children, family income, and education.

As can be seen, the coefficients for children on marital interaction and happiness were all negative. As time progressed, the effect diminished until the effect size was small. So, although children do negatively impact marital interaction and happiness, the effect diminishes over time.

In an original paper by Angeles (2009), they found that having kids increases life satisfaction and that the effect is positive and large and increases with the number of children one has. The caveat is that it depends on the individual’s characteristics and geographical and cultural factors, so life satisfaction increases for specific people who have kids. After fixing a coding error in the original 2009 paper, it was found that, after correcting the problem, the main results of the paper no longer hold. The effect of children on the life satisfaction of married individuals is small, often negative, and never statistically significant.

Also looking at General Social Survey data, Elmslie and Tebaldi (2014) found that children are negatively associated with happiness in marriage for both men and women, but the coefficients were pretty small. When looking at the effects of # of children on general happiness, there was a small but positive coefficient.

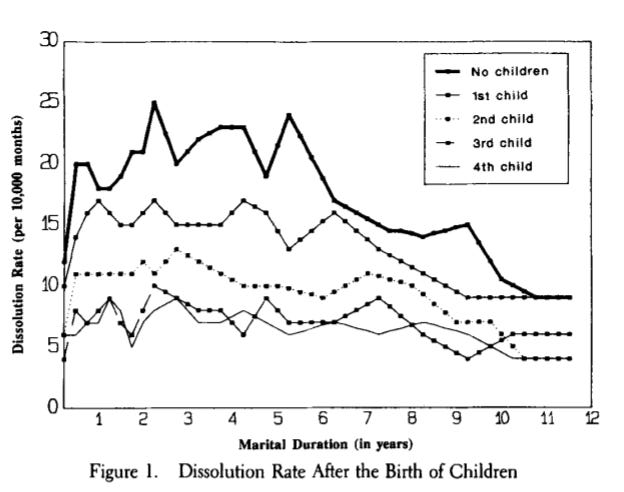

Heaton (1990) looked at the June 1985 Current Population Survey and held marital duration and age (includes maturation, age during marriage) constant. The sample was also restricted to white non-Hispanic first marriage so remarriage, premarital fertility, and race did not bias the results.

As can be seen, relationships with no children and relationships with 1 child see an increase in their dissolution rate, but it lowers as time progresses. Couples with at least one child have a dissolution rate about 74% as high as childless couples. The dissolution rate drops to 63% after the birth of the 2nd child, then 56% after the birth of the 3rd child. Having a 4th child has no effect. So, having a large family doesn’t seem to negatively impact the chances of marital dissolution, but having less than 3 kids does have a negative effect.

Cherlin (1977) found that children in preschool ages deterred the chances of separation and divorce, but stopped doing so once all the children were in school. Akin to Heaton, Thornton (1977) found that women with large families and those with no children were the most likely to experience disruption. Those with moderate amounts of children have the lowest disruption rates. Looking at the effects that a child’s gender has on the risk of marital disruption, sons reduced the chances of marital disruption by more than 9% when compared to daughters. This could possibly be explained by fathers spending more time with their sons and thus leads to a greater increase in family involvement (Morgan, Lye, and Condran 1988).

Twenge, Campbell, and Foster (2004) ran a meta-analysis on marital happiness by couples with children and couples without children. The difference between these two groups was d=-.19, meaning that couples with children had lower marital satisfaction than those without children.

So, it seems that couples without a child are happier than couples with a child (see Dickinson 2018 for more). It’s probably not that children directly lead to lower marital satisfaction, but rather than having children leads to X, and X leads to lower marital satisfaction. Indeed, Twenge, Campbell, and Foster note:

The transition to parenthood may (a) increase chores, stress, and strain, partially due to decreased time for discussion (Anderson, Russell, & Schumm, 1983; Lopata, 1971); (b) interfere with couple companionship (Glenn & Weaver, 1978; White, 1983); (c) interfere with the couple’s sex life (Blumstein & Schwartz, 1983); (d) overload the number of social roles accumulated by the new parents (Rollins & Galligan, 1978); (e) exacerbate inequity between partners that under benefits wives (Feeney, Peterson, & Noller, 1994); and (f) create negative evaluations of marriage, especially among nontraditional women (Belsky, Lang, & Huston, 1986)

Although it may seem like having children can hurt a marriage, it’s not as simple as “have kids, get bad marriage.” Instead, it largely seems to be dependent on characteristics within individuals.

Blanchflower and Clark (2019) found that once you control for financial difficulties, children do raise happiness among couples but the coefficient is small.

So, it seems that having children leads to stressors like time & energy demands, sleep deprivation, work-family conflict, and financial strain (Glass, Simon, and Andersson 2018), and controlling for financial difficulties shows that children do raise happiness.

Myrskyla and Margolis (2012) found that happiness increases in the years after the birth of the first child but decreases later on. Those who had children at older ages and who had higher SES had more positive and lasting happiness. While happiness increased after a 1st and 2nd kid, the 3rd child didn’t increase happiness.

In summary, children do not help relationships, but this association is also not casual. Instead, children lead to variables that make marital satisfaction decrease, and this causes a negative correlation between children and marital happiness. Once the income is controlled for, children do raise happiness but the effect is small. This means that people who can afford kids reap the benefits while those who can’t burden the problems, and the happiness that children do produce isn’t that large.

Premarital Sex

Another aspect of traditionalism is to reframe from having premarital sex. Besides the religious justification for this, it’s often argued that having premarital sex leads to negative psychological outcomes. Due to this, it’s important to see if there is a cause-and-effect relationship as some people imply.

In one of the most widely cited studies on this issue, Rector et al. (2003) found that women who had sex at an earlier age and who had more pre-marital partners were more likely to have an STD, give birth out of wedlock, be single mothers, can’t form a stable marriage, have higher levels of maternal poverty, were more likely to have an abortion, and were less happy. When looking at the statistical significance for these results, it’s hard to know what alpha the researchers even used. As it says in the study,

The percentage and other estimates in the charts were subjected to a rigorous “jackknife” analysis to gauge the statistical significance of the differences of the extreme values. All of the charts presented have differences that are statistically significant at the 95 percent confidence level. That is, in all cases, the percent reported on the left side of any given chart is statistically different from the percent reported on the right side of the chart.

Simply saying that the results were statistically significant doesn’t tell us much without knowing what alpha was used, or an effect size to see the magnitude of the difference.

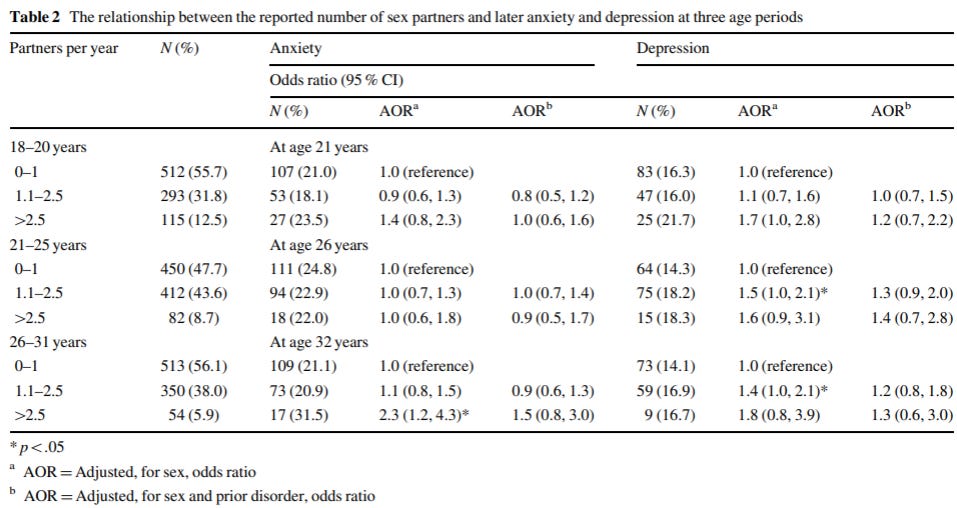

Looking at a New Zealand cohort, Ramrakha et al. (2013) found that the number of premarital partners was not significantly associated with later anxiety and depression.

When looking at substance dependence, there was a statistically significant correlation that remained once prior disorders were controlled for. It’s unknown if this correlation is even casual, as the authors propose some possible ways causality runs: (1) Sexual risk-taking and substance abuse may be part of a cluster of risk-taking in adolescents; (2) Alcohol can encourage PMS; (3) Something about having more sexual partners puts people at risk for substance abuse. More research should be needed to see which way causality runs, but the 2nd proposal may be the correct one. One study by Fielder and Carey (2010) looked at first-semester female college students and 64% of PMS encounters follow alcohol abuse. More research is needed, though. Regardless, it seems that having multiple sexual partners and later mental health issues is not statistically significant.

The researchers found that when looking at the correlation between multiple sexual partners and controlling for prior mental health, there was no statistically significant correlation between the number of sex partners and later anxiety and depression for those who had mental health issues at a later assessment.

After controlling for prior mental health and prior substance disorder, there remained a statistically significant correlation between the number of pre-marital sex partners and substance abuse that developed in a later assessment.

In looking at later psychological and health outcomes, Else-Quest et al. (2004) utilized a nationally representative sample of Americans and measured their relationship status at first vaginal intercourse, age of first vaginal intercourse, the context of first sexual experience, sexual dysfunction, sexual guilt, overall health, lifetime STDs, and life satisfaction.

Once the context of the first experience was controlled for, it showed that if the first sexual experience was prepubertal, forced, with a blood relative or stranger, or the result of peer pressure, drugs, or alcohol, then it leads to lower psychological and physical health. So, the correlation between pre-marital sex and negative outcomes could be a result of the context of the first sexual experience, not that simply having pre-marital partners leads to this directly. Furthermore, there seems to be no causal association between premarital sex and mental health issues for either those with prior mental health issues or those who developed them later on.

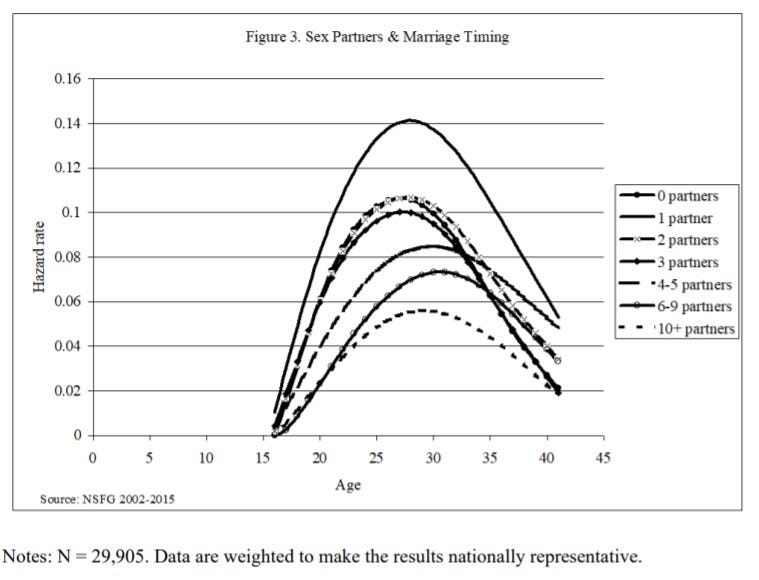

Looking at 17 waves of the NLSY97, it was found that having more sexual partners doesn’t stop women from getting into marriage. When comparing those with multiple sexual partners to those with none or a few, the women that had more sexual partners simply got married at a later age. Virgins also have a lower odd of getting married, but this could also be partially explained by unmeasured variables (Wolfinger and Perry 2021).

A meta-analysis on 34 studies also found risky sexual risk-taking was unrelated to depression and anxiety (Crepaz and Marks 2001).

Confounding variables also explain the relationship between pre-marital sex and divorce. In a sample of 100 divorced persons and 50 adjusted couples, premarital sex did not have a significant effect on creating the divorce (Kunda and Gosh 1977). When it comes to the correlation between premarital sex and divorce, the relationship is not causal. Kahn and London (1991) looked at the 1988 National Survey of Family Growth, specifically women aged 15-44. The sample was limited to white women since there was a small number of non-white virgins in the data.

Once unobserved differences were controlled for, there was no statistically significant correlation between premarital sex and divorce. This means that ”the results suggest that the observed relationship between virginity status and the risk of divorce reflects neither a direct nor indirect causal relationship but rather is a function of the selectivity of virgins concerning unobserved variables that also protect against the risk of divorce.” In other words, premarital sex does not cause divorce, but rather within-individual variables do.

Focusing on happiness, Perry, Grubbs, and McElory (2021) found that women who had pre-marital sex were more likely to be unhappy than those who did not have pre-marital sex, but this was only true for those who thought it was immoral. Thinking pre-marital sex is immoral can lead to lower happiness rather than pre-marital sex itself.

Pre-marital sex thus does not seem to be harmful towards relationships. Sometimes when arguing that PMS/ MPS does not have negative effects, the issue of oxytocin comes up. For example, writing in the Christian Post, Blair (2013) notes:

According to neuropsychologist Dr. Tim Jennings in the Conquer Series report: “When you have premarital sex, your reward circuitry is bonded to them now, and it will be much deeper and hurtful. Oftentimes, in breakups of people who’ve been sexually active, they can’t tolerate the sense of emptiness, so they rush into another relationship. The neuro circuits did not have time to reset, and so they’re impaired in their ability to bond with the next person, and they may become sexually active with them. This is just a repetitive cycle, and there are real impairments in bonding going on.” “Knowing how these neurochemicals interact and change the brain help us understand why sex is meant [to be kept] within the boundaries of marriage,” the reported noted.

Obviously, they’re arguing against casual sex through the lens of religion, but is there any truth to this? Is oxytocin going to be affected by casual sex? No.

Oxytocin is one of many neuropeptides that are produced and found in mammals. It plays a part in many things, like sexual arousal (Blaicher et al. 1999; Cera et al. 2021), helps a mother bond with her child (Uvnas-Moberg 2016), and even during social interactions. From this evidence, it sure does sound like oxytocin is the love hormone, right? No, especially since oxytocin is released in stressful situations (Taylor et al. 2006) and not just ones that promote bonding. Clearly, the effects of oxytocin are not as straightforward as some have argued, nor does it support the idea of oxytocin being the “love hormone”.

Furthermore, there is 0 evidence that having PMS/ MPS will lead to a decrease in oxytocin or anything of that nature. It’s just a claim being made that has 0 evidence to suggest if it’s true or not.

Conclusion

Overall, as bitter of a conclusion it might be to some readers, it does not seem like the different aspects of traditionalism positively benefit people. Whether it be from relationships to having children, to even pre-marital sex, these variables are either not associated with negative effects as having been argued, or the story is more nuanced than what traditionalists have argued before about them.

Cool stuff.

The findings remind me of this music video "Gives You Hell" by the All American Rejects.

Didn’t you have an instagram post on this where your stance was different?