NoFap: What Does Science Say?

The effects of No Fap on one's mental health, sexual functioning, relationships, and testosterone are either placebos and aren't causal effects.

Every November, thousands of young men and women participate in No Nut November, a challenge in which participants attempt to not masturbate and ejaculate for all of November (some just edge, but I am not sure if that’s allowed). This is then followed by Destroy Dick December, a time in which some participants go on to have sex with others or themselves. However, No Nut November seems to be somewhat aligned with No Fap. What is No Fap? It’s complicated, but in this article, I’ll argue that the supposed effects of No Fap on one's mental health, sexual functioning, relationships and testerone aren’t real effects and just placebos.

No Fap, oftentimes just called Nofap, is a variation of No Nut November, but this challenge takes place for as long as one can because it’s believed pornography is harmful to its consumers. Any young man who often felt shame for masturbating has Googled “No Fap” and come across multiple videos of people arguing the benefits of No Fap. Before we can get onto this, it’s important to know the history of NoFap in order to have a better understanding of why it is that they argue No Fap has health benefits.

In 2011, Alexander Rhoades created the sub-Reddit r/Nofap which spawned from a 2007 Chinese study finding that refraining from masturbation led to an increase in testosterone (Jiang, Xin, and Shen 2002). NoFap was then created to be a support group to help people stop masturbating and “overcome porn addiction, porn overuse, and compulsive sexual behavior. We’re here to help you quit or reduce porn use, improve your relationships, and reach your sexual health goals” [bold was not added by me]. No Fap, though, is not just a place where users can attempt to quit masturbating and watching porn, but also a place where users often say how harmful pornography is and how not masturbating would improve their life. The complicated part is that science is much more nuanced than what they claim.

Going back to the young men who felt shame about masturbating, the odds of them finding more information on No Fap have certainly increased due to their shame towards masturbation. A quick Youtube search for “No fap” brings up videos like this:

People who make these types of videos often discuss how as you stop masturbating, your testosterone increases, psychological well-being increases, you start to focus on other stuff more, and, as I remember hearing when I was younger, women would start to notice you. Young men who watch these videos and do not understand the science about pornography and masturbation would certainly believe these things to be true, but No Fap pushes bad and misleading science.

The chapters below showcase what topics will be of interest for easy navigation.

I. The Claimed Benefits

II. Psychological well-being

III. Sexual Functioning

IV. Relationships: Partners and Sex

V. Testosterone

I. The Claimed Benefits

A look at these videos offers insight into what No Fap participants believe not masturbating would do to oneself. Improvement Pill’s video, which is the most watched video on the issue, says he uses “scientific evidence” to back up his claims (2016). To begin, Improvement Pill (IP, henceforth) notes that dopamine, which is a neurotransmitter associated with rewards and motivation. Drugs, which release dopamine, decrease the number of dopamine receptors one has. Because of this, it leads to sexual dysfunction, social anxiety, etc., but according to IP, pornography has the same effects as drugs on dopamine. In fact, pornography releases more dopamine than other substances due to something called the Coolidge Effect; where people would get tired of one partner and want to move on to another one.

At 4 minutes in, almost no scientific evidence is offered to show the benefits of No Fap. In fact, IP pushes the Coolidge Effect onto pornography consumption with no evidence, instead referring to a study done on rats and extrapolating this to humans, an issue since animal models are poor predictors of human reaction to stimuli (Shanks, Greek, and Greek 2009; Bracken 2009) and the Coolidge Effect has not been shown to work with pornography and mate preference (Scully and Watkins 2022). According to IP, the constant use of pornography messes with one’s dopamine production, and thus, pornography is the reason that many men have social anxiety, depression, and lack of motivation. However, evidence does not suggest that pornography messes with one’s dopamine receptors, calling into question this claim (see Stormezand et al. 2021). Finally, IP notes that those who partake in No Fap report better social skills, less anxiety, higher libido, and higher motivation. No scientific evidence is offered for this, or that pornography decreases dopamine and leads to these issues.

Cole Hasting (2020) discusses semen retention, which is just refraining from masturbation, and one would assume pornography, too, and notes the health improvements caused by semen retention. Semen retention slightly differs from No Fap as it also refrains from ALL sexual activities, not just masturbation and pornography. According to Cole, society wants you to remove masculine energy from your body by promoting sex. According to Cole, semen retention increased energy (being happier, being more productive, more sleep), keeping in semen increases your testosterone and drive [admits there is no scientific evidence for this], helps you find your purpose in life, increases emotional control, people can sense more energy from you by attracting a higher vibration, and better muscle improvement.

Okay, lots of stuff said but even Cole’s own video does not suggest this is because of semen retention and not watching pornography and masturbating. As Cole even says, he stopped taking naps, became more productive, and stopped smoking cannabis and hanging out with friends, but of course, when you stop doing certain stuff and try other stuff, more motivation would be allocated to the new stuff and not the old stuff. It’s as if someone said that not having sex for a month lead them to read more books, and sex was hindering them from doing this all along. No, they could still do it, they just did not choose to do it, to begin with. Instead, they blame sex instead of themselves for not allocating their time more efficiently. The student who says they play too many video games and that’s why they are doing badly in school has no one to blame but themself; they could still play video games and do good in school, but they decided to put all their energy into video games instead.

X-Xing (2021) says that No Fap increases motivation (better psychological well-being, etc.), becoming a leader of men, emotional control, you start to attract women (possibly because it increases testosterone, women can somehow sense this, people get into relationships), balanced hormones like testosterone, balanced emotions (you won’t be anxious, for example), leads to self-improvement, better dopamine which leads to better psychological well-being and taking risks, better concentration, no brain fog where your brain stops thinking, and even getting a deeper voice. Once again, no evidence, but some of these benefits make no sense. Getting a deeper voice? Having women be able to somehow sense you don’t masturbate?

Similarly, Self-Developed (2022) makes similar outlandish claims about the benefits of not masturbating. According to him, refraining from masturbation can increase facial hair, change your facial structure, increase testosterone. Remarkably interesting benefits, especially since it increases facial hair. Why haven’t doctors been telling young men who struggle with growing facial hair to just stop masturbating?! What does Self-Developed know that we don’t?

Okay, some silly claims made by some YouTubers, but is what they’re saying that different than what No Fap members think? According to one post on the forums, refraining from masturbation gave them more time on their hands, more energy, better sleep, better social skills and not viewing women as sex objects, less anxiety, more confidence, taking care of their appearance, better nutritional intake, being clean. Hmm, I am sensing a pattern here. Masturbating isn’t stopping you from doing these things, you’re just lazy. What this user claims to have benefited from fits in line with what Healthline says, according to what other people have claimed: better mental and physical benefits, with some of the examples aligning with what others have claimed. Some even say that quitting masturbating helped their erectile dysfunction!

We can make general themes about the benefits of No Fap:

Better psychological well-being

Better Sexual Functioning

Relationships: Having real sex and getting into relationships

Increase in testosterone

Let’s examine the evidence for this and see if these benefits have any scientific backing.

II. Psychological Well-Being

According to users on No Fap forums, masturbation, and pornography lower psychological well-being. According to one user on Reboot Nation, “All my life I was wondering what may have caused the Anxiety, existentialism and depression. It was a deep underlying porn addiction.” While not an anti-masturbation and anti-pornography forum, one user on a mental health forum said that “I have a strong feeling that fapping and p0rn makes my depression worse.” Another user on the No Fap forums asked if “…other forum users have experienced mental health improvements with the NoFap. I have read of dramatic improvements in some cases…”

The underlying mechanism assumed in these cases is that pornography consumption directly leads to lower psychological well-being. However, for this to be true, we must find that pornography actually influences psychological well-being. There are some studies to support this, but it’s not as simple as some make it out to be.

The infamous, and now dead, Gary Wilson, who ran the site Your Brain on Porn and who authored a book under the same name argued that pornography is associated with lower psychological well-being. One such page on Wilson’s site offers multiple studies showing pornography users report lower mental health.

Some of the studies Wilson cites are worth going through. One of the studies is Griffiths et al. (2018), found that pornography consumption was correlated with body dissatisfaction, and positively correlated with eating disorder symptoms and thoughts about using steroids.

In their standardized regression model, we find that the effects of pornography use are very small, and their r^2 is very low, not even explaining 1% of the variance, except in the quality of life. The degree to which pornography explains these relationships is extremely low, so there are many other variables for all of this and not just pornography. Wilson does not mention these effect sizes.

Another study is Lim et al. (2017), done on 941 Australians through a cross-sectional design. The adjusted hazard ratios (AHR) show that reporting mental health problems in the past 6 months was associated with a 20% increase in viewing pornography.

However, the use of this study by Wilson runs under the assumption that people, especially young people, will often not go through events that affect their mental health. Why is it an issue that young people might have issues unrelated to pornography, and thus their mental health decreases, and they see an increase in pornography use? It could be that pornography provides a way to escape these issues temporarily and provide sexual pleasure which makes them feel better, not that pornography itself is causing these mental health issues.

While not especially important, it’s funny Wilson’s site continues to cite Beyens et al. (2015) to show that pornography is associated with lower academic performance but makes no mention of another study that was unable to replicate these effects (see Sevic, Mehulic, and Stulhofer 2018). This has nothing to do with psychological well-being, but Wilson included it to show that pornography is associated with lower cognitive outcomes.

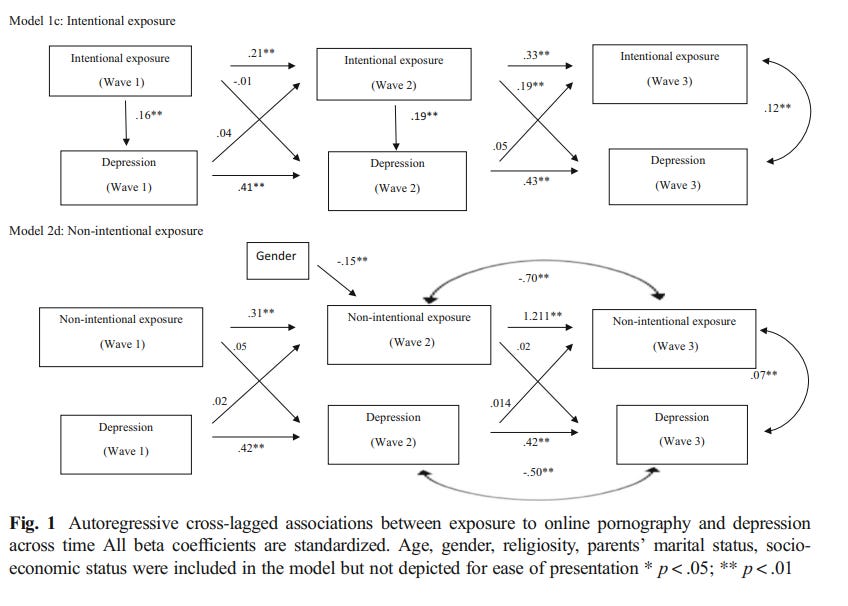

Of the few longitudinal studies cited by Wilson’s site, one of them is Ma (2019), a longitudinal study done on 1,401 Chinese adolescents. The study did find that intentional exposure to pornography was associated with depression, but prior mental health was not adjusted.

Funny enough, Wilson’s site makes no mention of the other models, finding no relationship between pornography consumption and life satisfaction.

Many of the studies Wilson cites are cross-sectional, and there are other studies besides Wilson's cited ones showing related results (Butler et al. 2018; Harper and Hodgins 2018, to name a few).

When better models with better designs are utilized, there is no causal or consistent relationship between pornography consumption and psychological well-being.

When it comes to body satisfaction, the idea that pornography can lead to thinking about one’s genitals in a negative light seems possible. If people consume pornography, chances are they’re being exposed to actors who have been selected because they have specific body types, like large breasts, a specific looking vagina, a large penis, etc. However, while this might have been true at one point, the rise of amateur pornography seems to have led to a spotlight on more realistic bodies; people with average penis sizes, non-porn-perfect breasts, etc., can now make their own content. Thus, consumers can find specific bodies that may reflect their own to watch.

The top hypothesis is just one I thought off, and albeit, I do not have much evidence to support that this is the driving force for the study I will cite, but I do think it’s a good explanation. Hustad et al. (2022) found that pornography exposure was not correlated to one’s genital self-image for both males and females.

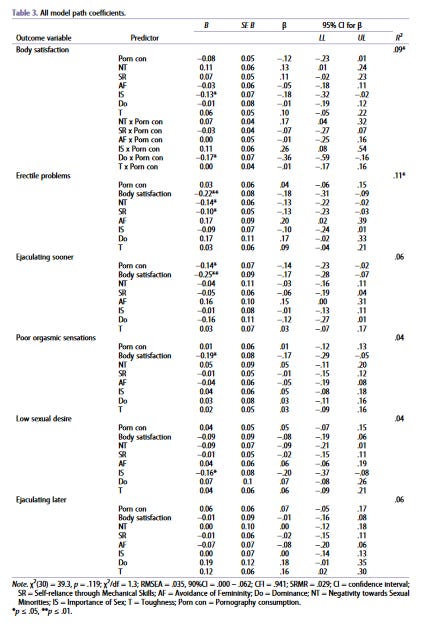

Furthermore, the negative relationship between pornography consumption and body satisfaction among males can be driven how they view masculinity. Komlenac and Hochleitner (2021) asked males questions about things related to masculinity, like “Avoidance of Femininity (AF), Negativity towards Sexual Minorities (NT), Self-reliance through Mechanical Skills (SR), Toughness (T), Dominance (Do), Importance of Sex (IS), and Restrictive Emotionality (RE).” It was found that there was a negative relationship between pornography consumption and body satisfaction, but this relationship was mediated by views on masculinity. Specifically, it was male dominance that mediated it.

Low pornography use and high pornography use were not associated with lower body satisfaction in men who did not endorse high dominance.

Longitudinal data from Doornwaard et al. (2016) found that low-psychological well-being predicted higher levels of pornography use later (when I say higher, I mean lots, and lots of porn, not what some think is a lot, like a couple of times a week).

Psychological issues come before pornography use, not after. Further longitudinal data provides more evidence of no relationship/ inconsistent relationships between pornography use and psychological well-being.

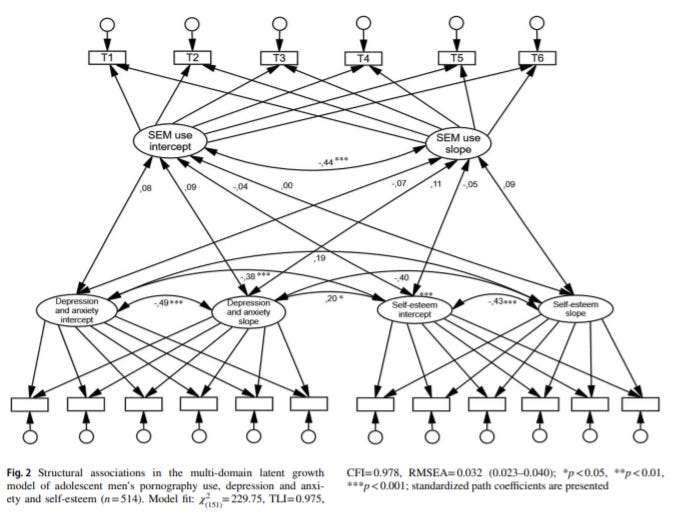

Stuholfer, Tafro, and Kohut (2019) measured psychological well-being through 6 waves using a sample from the longitudinal data set from the Prospective Biopsychosocial Study of the Effects of Sexually Explicit Material on Young People’s Sexual Socialization and Health. At baseline, there was a relationship between pornography use and anxiety and more depressive symptoms (r=0.19, p<0.001), and lower self-esteem (r=-0.19. p<0.001) for women. For males, however, there was no relationship.

LGC models showed that as time went on, there was a decrease in depression and anxiety, but there was an increase in pornography consumption and self-esteem. For males, anxiety and depression also decreased as time went on. How would this be so if pornography were truly harmful to one’s psychological well-being?

Similarly, Kohut and Stulhofer (2018) found no relationship between pornography consumption and anxiety and depression for males in both a Zagreb and Rijeka panel. For women, there was no relationship except for self-esteem. For females in both panels, low psychological well-being was associated with pornography use, showing pornography to escape problems, but only in one panel. In the Zagreb panel for males, adjusting for prior mental health showed no relationship between pornography consumption and later depression and anxiety. For males in the Rijeka panel, there was no relationship between pornography consumption and later anxiety and depression when adjusted for impulsivity and adverse family environment. For females, there was no relationship in the Zagreb panel, but there was a relationship in the Rijeka panel once further controls were adjusted.

Considering there is no causal or consistent relationship between pornography consumption and lower psychological well-being, why are NoFap users and those like those who hold NoFap ideas experiencing lower psychological well-being?

Moral issues, not pornography, explain the relationship. When individuals who are morally against pornography consume pornography anyways, they experience lower psychological well-being. This is not because of pornography itself, but them going against their own morals.

This was a finding in Perry (2017) using a nationally representative sample.

Again, found in a meta-analysis by Grubbs et al. (2019a, 2019b).

The same holds true when looking at masturbation. A small review of the available literature by Mascherek et al. (2021) says that,

Negative effects of masturbation are caused by feelings of guilt, moral attitudes, and religious beliefs and not by the behavior itself, for which no ill effects have been found (Coleman, 2003). Pivotal for negative health effects of masturbation is a subjective evaluation of the behavior and its accompanying physical reactions. Massive guilt is experienced by some individuals, which then, in turn, influences psychological and relational well-being. One study (Castellini et al., 2016) reported that this so-called ego-dystonic masturbation was significantly related to higher scores of anxiety and depression scales, sexual dysfunctions, and relational as well as intrapsychic problems in a sample of over 4,000 human male outpatients of an andrology and sexual medicine clinic in Italy.

Thus, it does not seem like pornography itself or masturbation is causing lower psychological well-being among its users. Most likely, NoFap users and others have moral issues with pornography, and thus moral issues, not pornography, lowers psychological well-being. The increase in psychological well-being after refraining from pornography seems to represent feeling good about not going against one’s morals, not pornography stopping harm from being caused itself.

III. Sexual Functioning

As was noted above, some NoFap users believe that pornography consumption is positively correlated with erectile dysfunction. However, this is not a view that has been restricted solely to users against pornography and masturbation, but also among some mainstream outlets. Going back to Wilson’s book, he cites Wery and Billeux (2015), a study on 434 men who engaged in online sexual activity (OSA).

A look at the multiple regression analysis finds that lower erectile functioning was associated with an increase in OSA, but not that OSA causes erectile functioning issues. In fact, as the paper says, “The third regression analysis revealed that higher sexual desire, lower overall sexual satisfaction, and lower erectile function predict problematic use of OSAs.” How does one confuse this with “…there was already evidence that porn video viewers tended toward…declining sexual responsiveness”, effectively implying that pornography is the cause of these issues?

A review of Wilson’s book would require a longer article, but if one study is being misrepresented, it calls into question what he claims about other studies cited. This is not the first time Wilson has pushed the idea that pornography consumption can cause erectile dysfunction. In Park et al. (2016), Wilson et al. claim that “Since then, evidence has mounted that Internet pornography may be a factor in the rapid surge in rates of sexual dysfunction.” Wilson et al.’s evidence for this is poor, referring to studies in which some of the findings are ignored or trying to draw conclusions between a simple correlation. The first example of this is when they show that males who visited an erectile dysfunction site reported watching pornography, but this does not show causality or an effect size, to begin with.

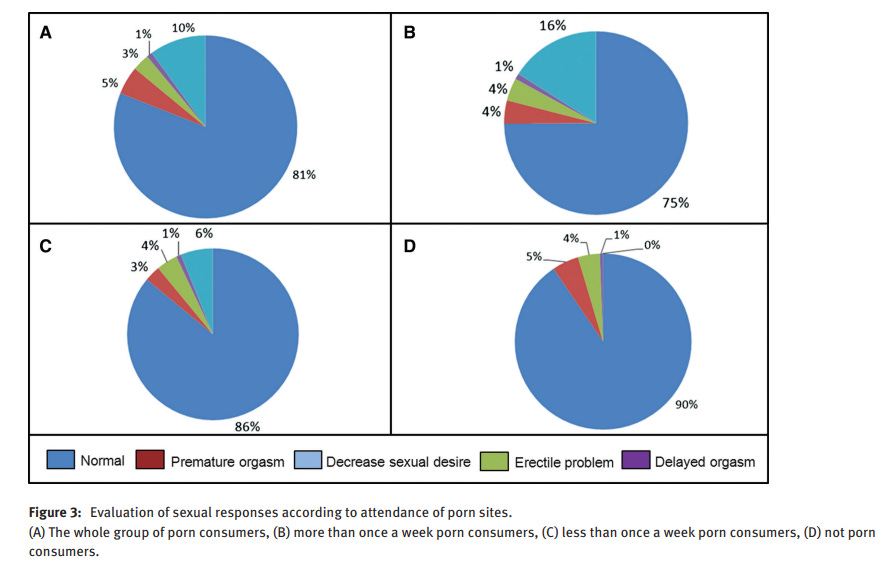

Another study was shown to shows that pornography harms sexual functioning from the authors is Pizzol, Bertoldo, and Foresta (2016). Wilson et al., though, make no mention of one of the findings from the study: self-reported rates of erectile dysfunction among high schoolers (N = 1,492) equal across the different cohorts.

Rates of erectile problems across the cohorts broken down by how often they consume pornography were equal. Those who watched no pornography at all reported erectile problems at the same rate as those who watched pornography more than once a week and those who watched pornography less than once a week. The study did have clinical visits, but no mention is made of how erectile problems were measured, leading it to be based on self-reports; this calls into question the validity of the studi’s findings since how accurate would a high schooler’s perception of their sexual functioning even be?

Park et al. cite multiple clinical reports showing that once someone stopped using pornography, their erectile problems were no more. However, clinical data is not representative of the average person since these individuals who seek help tend to have comorbidities (Black 2022: Chapter VI). In the other studies Park et al. cite, they offer two studies that make use of statistical models to show that pornography consumption is not associated with erectile dysfunction, but their criticisms of these studies rest on shaky ground. This being that one comment on one of the studies had a non-random sample and even small effects can be significant, but their citation for this makes no effort to show that if these issues were fixed, the relationship would switch around.

Park et al. and Wilson aren’t alone in making this claim. Fradd (2014: 93) remarks that “With the increasing availability of pornography has come an increase in the number of cases of sexual performance issues, such as erectile dysfunction (ED), among young men.” Fradd’s evidence for this claim relies on evidence finding an increase in erectile dysfunction among young men. The mechanism in which this relationship between pornography consumption and erectile dysfunction runs is hinted at by Fradd:

Online porn viewing is, among other things, novelty-seeking behavior: constantly clicking, greedily keeping multiple tabs open, always looking for the next girl, the next sexual buzz. A real woman—no matter how attractive —is only one woman. A man this obsessed will have difficulty finding her arousing.

An interesting relationship and the concerns about pornography use and erectile dysfunction is a fear warranted by young men. Writing in Rolling Stone, Dickson (2017) says that “Yet many young men in their twenties and thirties are turning to sites like Reboot Nation – according to Deem, it has approximately 10,000 visitors per month – as well as similar websites like Your Brain On Porn and the subreddit NoFap, to report experiencing symptoms of erectile dysfunction. And the one thing they have in common, they say, is a healthy diet of Internet porn.”

First, the most often cited study, which even makes an appearance in Wilson’s book is Voon et al. (2014). Voon et al. looked at 19 males with Compulsive Sexual Behavior (CSB) and 19 healthy volunteers (N = 38), in other words, males without CSB. 11/ 19 males with CSB had erectile functioning issues, and when compared to healthy volunteers, those with CSB “experienced more erectile difficulties in intimate sexual relationships but not to sexually explicit material." The difference in achieving an erection while in a relationship was significant (d= 0.69). The small sample in this study is an issue, but also reflects a general issue in neuroscience. Because of the small sample leads to low statistical power (Button et al. 2013; Neuroskeptic 2014), it casts doubt on how accurate these findings are.

Jacobs et al. (2020) looked at 3,419 men and women and administered them the Cyber Pornography Addiction Test (CYPAT), International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5), and Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Concise (AUDIT-C) online. According to the authors, there is a significant correlation between problematic pornography consumption and erectile dysfunction, but no correlation when looking at pornography consumption time and erectile dysfunction.

Unfortunately, Jacobs et al. do not provide an effect size so we can see the strength of the effect size. However, problematic consumption was associated with erectile dysfunction, but not time spent consuming pornography. This is important since those who classify into the problematic group represent a small % of users who watch pornography (see Bothe et al. 2019). Since users with problematic pornography consumption have other pre-existing psychological issues (see Bothe et al.), they may not reflect the average pornography consumer and their issues with erectile functioning might be related to something else.

Dwulit and Rzymiki (2019) conducted a literature review and found 7 studies, some of which will be talked about down below, and found that the evidence on pornography causing erectile dysfunction is not clear. While the Dwulit and Rzymiki review is interesting, it suffers from the issue of taking Park et al.’s work as evidence for a relationship. This is an issue since Park et al. offers case studies to show a causal relationship, but this is not representative since it only tells us about the person in these case studies. Because of this, I disagree with Dwulit and Rzymiki’s method of mixing unrepresentative studies with better studies and using this as a pivot to say that there is no straightforward evidence.

Fears of pornography consumption causing erectile dysfunction are only warranted if there is a relationship between the two. However, once proper statistical models are used to estimate the relationship between both variables, there is no causal or consistent relationship between the two.

Landripet and Stulhofer (2015) had two samples that they used to see the relationship between pornography use and erectile dysfunction. Their first sample consisted of 2,737 Croatian, Norwegian, and Portuguese men. Their 2nd study consisted of 1,211 Croatian men. All samples completed a questionnaire that measured pornography use and erectile functioning.

At the bivariate level, pornography use was not statistically significantly related to erectile dysfunction for either the Norwegian group or the Portuguese group. In their Croatian sample for study 1, there was a link between pornography use and erectile functioning, but it was weakly correlated since Cramer’s V was 0.14. Frequent pornography use was associated with an increase in the odds ratio between pornography use and erectile dysfunction when compared to infrequent use, but this was only true for the Croatian sample. In their 2nd study, there was no statistically significant correlation between pornography use and sexual functioning. Furthermore, men who saw an increase in pornography use were not characterized by erectile dysfunction when compared to those with more stable use.

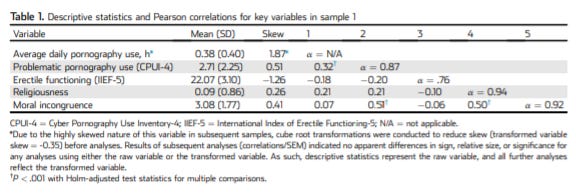

Grubbs and Gola (2019) looked at 147 undergraduates from the United States, 297 men who matched a nationally representative norm, and a convenience sample from MTurk who took part in a 1-year longitudinal study with 4 waves. In both 2 samples, there was no statistically significant relationship between pornography use and erectile dysfunction, and the effect sizes were small to weak.

In table 1 for sample 1, erectile functioning correlated with average daily pornography use at -0.18 and problematic pornography use at -0.20. Despite the small effect sizes, they lacked statistical significance. Equivalent results were found in sample 2, with weak effect sizes and a lack of statistical significance.

As can be seen, erectile functioning was weakly correlated with average daily pornography use, was not correlated at all with frequent pornography use, and had a small, but statistically significant correlation with problematic pornography use.

In sample 3, which was the longitudinal sample, average pornography use weakly correlated with erectile functioning with negative effect size, but it was statistically significant.

In their latent growth curve model, average pornography use didn’t seem to be a significant factor for younger men’s desire, erectile, or orgasmic difficulties.

Focusing on individuals with cravings and obsession with porn, Berger et al. (2019) found no statistically significant correlation between cravings and obsession for pornography with and sexual functioning. Even the coefficients were weak.

Buchholz et al. (2021) found that pornography use doesn’t predict erectile dysfunction, rather testosterone and sex drive predict erectile dysfunction.

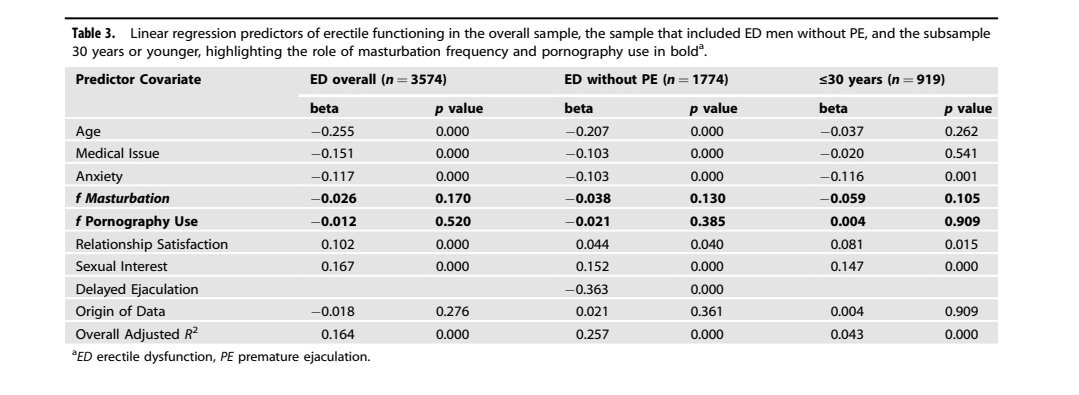

More recently, Rowland et al. (2022) found no relationship between pornography consumption and erectile dysfunction among people with erectile issues, people without erectile issues, and people below the age of 30.

In fact, neither frequency of masturbation nor frequency of pornography use were associated with erectile functioning or severity of erectile dysfunction. This is in stark contrast to what we would expect if we believed that more pornography use was negative for someone’s erectile functioning. The effect sizes can be seen below.

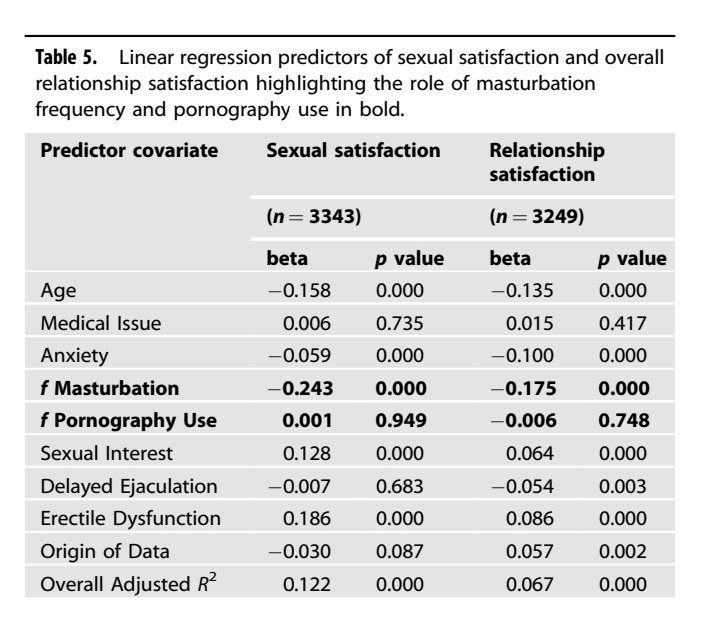

Focusing on sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction, the authors also found no relationship between masturbation frequency and pornography use frequency and sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction. This is contra to what other studies have found showing a negative relationship between pornography use and sexual and relationship satisfaction. The lack of relationship between pornography use and relationship satisfaction fits in line with a previous study (Perry 2019).

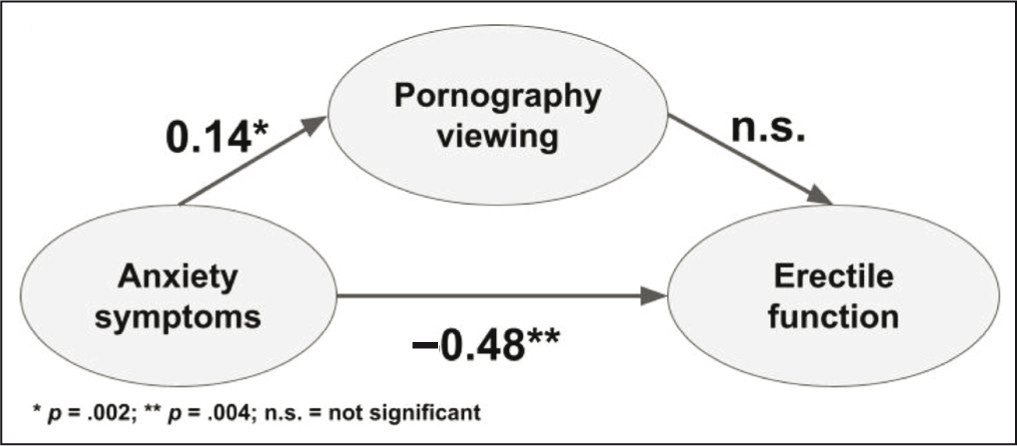

Prause and Binnie (2022) looked at 261 participants who partook in reboot programs and found that anxiety was associated with erectile dysfunction, and this effect was not moderated by pornography use.

Overall, it does not seem like there is any relationship between pornography use and erectile dysfunction.

While fears may be warranted, individuals who fear not being able to be aroused when they are with a partner do not have pornography to blame, but anxiety and other psychological issues. Much like the findings in Rowland et al., Jacobs et al. note,

“Experiencing performance pressure (“Pressure to perform in bed or to maintain an erection while having sex on a scale from 1 to 10”) resulted in an OR of 1.30 (95% CI 1.24-1.38; P<.001). Being single or having a new relationship was found to raise the odds of ED (OR 2.12, 95% CI 1.34-3.36; P=.001 and OR 2.27, 95% CI 1.40-3.66, P<.001, respectively) as compared with men in a longstanding (>6 months) relationship.”

Contrary to places like NoFap, Reboot Nation, and people like Gary Wilson, pornography use is not associated with erectile dysfunction.

The Komlenac study also finds no relationship between pornography use and sexual functioning in their regression.

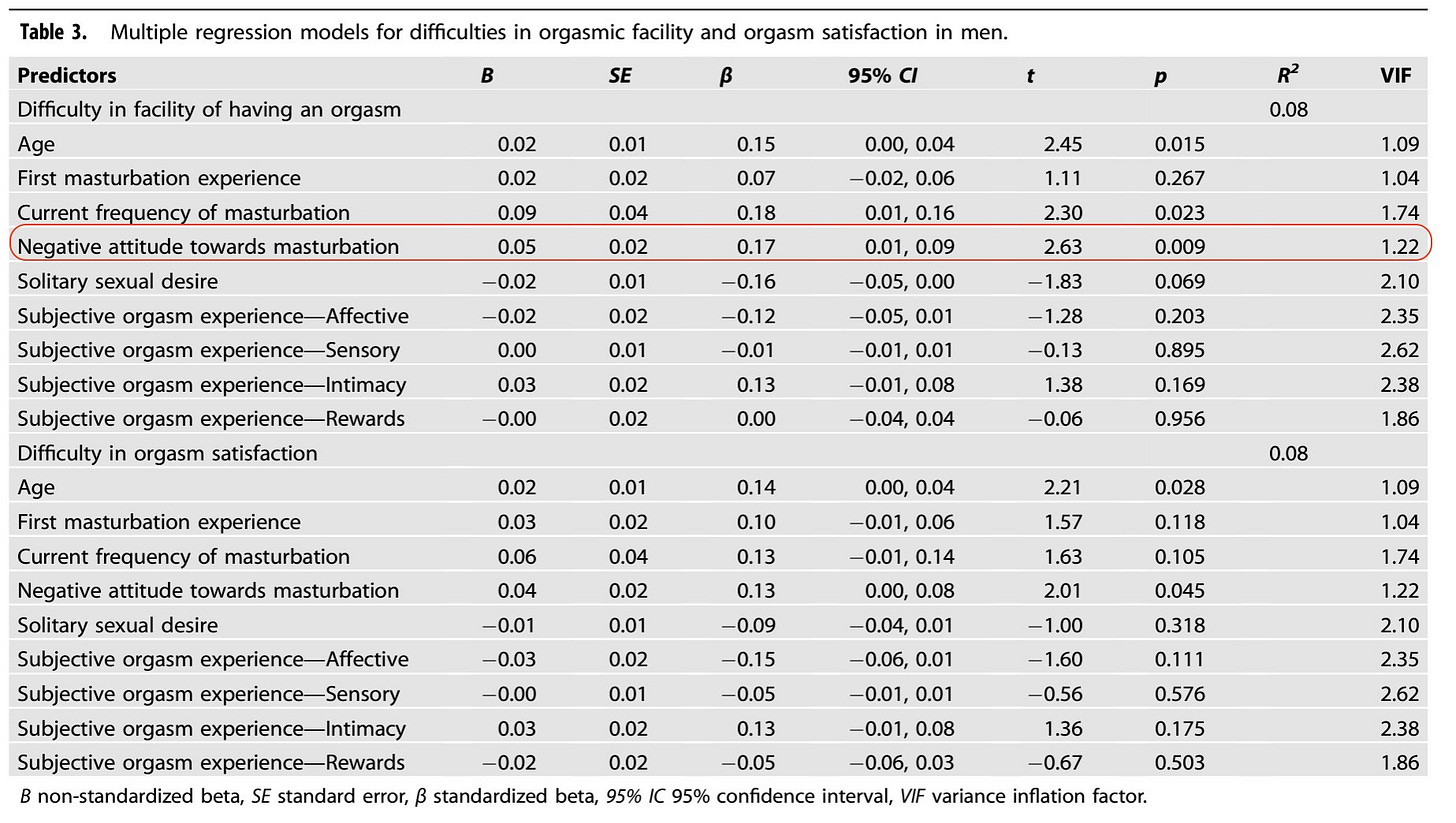

Ironically, negative attitudes towards masturbation, which were demonstrated in the examples above in the introduction, predict orgasm difficulties in males (Sierra et al. 2022).

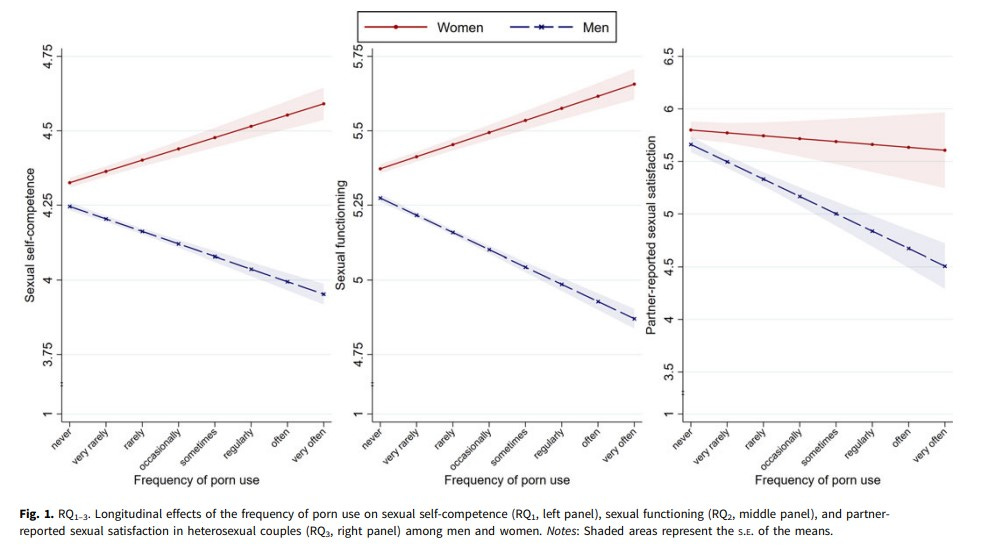

It may not be that pornography harms an individual’s sexual functioning in a causal way, but it may affect it within the context of relationships, specifically for men (see Sommet and Berent 2022).

However, this is due to how people view the realism within pornography content. Kuan, Senn, and Garcia (2022) find that it's not due to porn consumption, per se, but a mismatch between expectations created by porn and how real sex is.

These may seem similar, but there’s a difference. Simply watching pornography will not harm sexual functioning but thinking it’s realistic might since it causes a warped view of how real sex is.

Another issue is the lack of adjustments for solitary pornography consumption in studies that find negative effects. When couples watch pornography together, it’s associated with better relationship satisfaction (e.g., Daneback et al. 2009; Hoagland and Grubbs 2021; Grov et al. 2011; Kohut et al. 2021). However, solitary use alone might not be a causal effect either, as this can be due to lack of acceptance of pornography among a partner (Maas et al. 2018). In other words, how one person in a relationship personally views pornography consumption (not how they watch it, but how they view the topic of pornography) might affect their relationship rather than pornography causally leading to lower relationship satisfaction. The fact that most people in relationships don’t consider their partner viewing pornography as a form of cheating lends further support to this non-causal relationship (Negy et al. 2018).

Overall, it does not seem like pornography is detrimental to relationship sexual functioning or an individual’s sexual functioning.

IV. Getting into Real Relationships

Most people want to be in real relationships, but according to some NoFap videos, pornography stops people from getting into relationships. The ideal mechanism is that pornography would be preferred over real relationships (Zillman 2000). The data does not support this.

Perry (2020) found that between two nationally representative samples, those who watch pornography were more likely to want to be married (NFS OR = 1.25, p = 0.10; RAS OR = 1.07, p = 0.001).

Desiring marriage is different from being married, but even pornography consumers who watch more pornography than non-consumers are more likely to be married. The relationship differs by sex (Perry and Longest 2019).

Females who consume more pornography are more likely to be married that females who watch no pornography at all. However, among males, those who watch the most amount of pornography is less likely to be married, but moderate consumers are more likely to be married than people who don’t consumer pornography and those who watch excessive amounts. Those who don’t watch pornography at all are less likely to be married than moderate viewers, but more likely than high viewers. This might reflect individual differences between each class — in which individual differences within those who watch substantial amounts lead to a lower probability of being married.

However, not everyone wants to be married, to begin with. So, it’s possible that pornography consumers are less likely to be in general relationships than marriage. Herbenick et al. (2020) found a high OR for women between pornography consumption and being in another relationship, meaning not single or in a relationship, but just something else, but a low OR for everything else but “other.” This suggests that women with more niche sexual desires in the target-sexual behaviors may simply be in something else besides a standard relationship.

For men, there was a high OR across the board and no relationship between pornography consumption and being single.

Seems like pornography is not stopping people from being married or getting into relationships. Chances are that people in NoFap communities and the like simply aren’t even trying their best to get into relationships. This is also evident by the fact that pornography consumers are more likely to engage in sex with others (Rissel et al. 2016; Braun-Courville and Rojas 2008), further cementing the idea that people who subscribe to NoFap ideas may not be trying their best to get into relationships with others, but instead blame pornography.

V. Increase in Testosterone

This is one of those claims that doesn’t make sense when you hear it, but the more you hear it, the more likely you are to believe it even though the proposed mechanisms for this assumption have not been made.

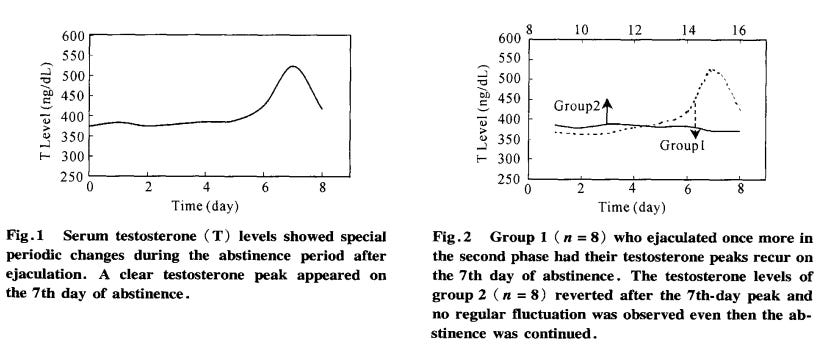

As was noted at the start, the belief that masturbation leads to lower testosterone comes from Jiang et al. (2003). In this study, 28 men were broken down into a control and experimental group. 14 males were told to abstain from masturbation for 8 days, and the other 14 were not.

As can be seen in figure 1, there was an increase in testosterone on the 7th day, but it decreased right after. Does not really seem like the increase in testosterone is permanent, something not mentioned by NoFap users who cite this study. Recently, this study has also gained traction for all the wrong reasons. Prause (2022) chronicles the fall of grace this study had, noting that 2/4 authors could no longer be found, the authors refused to disclose their data, and then admitted they did not have it. Exton et al. (2001) found related results, but they had a weak sample of 10 participants.

This doesn’t mean the study is wrong, though, as issues outside of our control could have caused this. However, has this study been replicated? Short answer: No.

Purvis, Cekan, and Diczfalusy (1976) had 34 subjects who had their testosterone measured before and after masturbation. There was an increase in testosterone, not a drop.

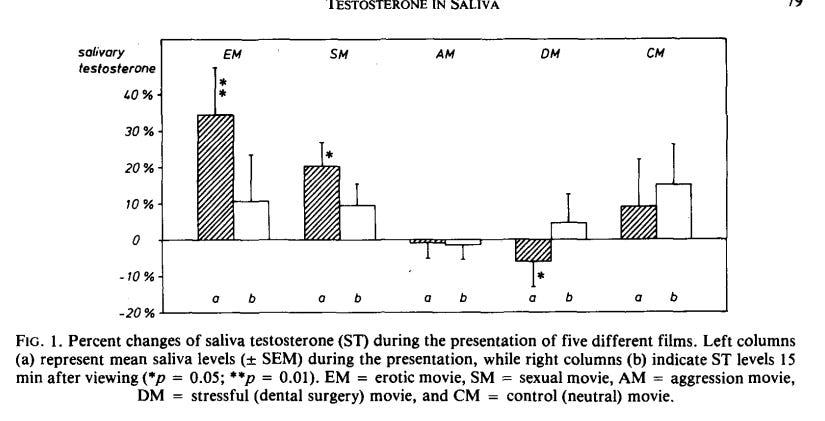

A small study of 12 people exposed athletes to several types of videos and then asked them to do squats. These videos included pornography, aggressive videos, etc., and were randomized in the experimental design (Cook and Crewther 2012). Like in the prior study, testosterone increased.

Hellhammer, Hubert, Schürmeyer (1985) exposed 20 participants full-length pornography films. What were the findings? Testosterone increased; it did not decrease.

Does not seem like pornography harms one’s testosterone levels.

The issue with Nofap is that contrary to what we should expect, which is helping others, programs like NoFap do more harm than good.

Chasioti and Binnie (2021) conducted a qualitative study on users who visit Reddit’s r/Nofap and r/Pornfree sub-reddits (N=40). According to the users, some went to pornography because of issues unrelated to pornography. Per one quotes,

I don’t know how all began. I am pretty sure it actually started when girls started to call me ugly. Afterwards I somehow turned to porn (No. 3, 169–170)

As the authors note, “Pornography consumption is regarded as a comfort zone and presented as a non-intimidating practice. On this basis, it can be argued that under these circumstances, pornography usage can be conceived as a psychological form of dissociation, acting as a defence mechanism against the prolonged violation experienced in adolescence.” This fits in line with what was claimed in the psychological section of this article: psychological issues come before pornography consumption, not after — and it does seem like even r/Nofap r/Pornfree users hint at this.

They also view pornography as a form of power. Pornography is a way to escape the terrible things happening in life, and pornography is a medium that allows one to take back control in their life and allows them to see themselves as powerful.

I think porn looks to me like a strong representation of myself. That is, it usually makes perfect sense to me that I would be a kind of sex-god. I use virtual reality as a method of seeing what to me seems like true reality (no 24, 1947–1949).

This is how my psychology works. I feel like a failure in social relationships, then I feel like a smashing success in sexual relationships through the medium of porn and frequent, lengthy masturbation (No. 25, 1958–1960).

A significant issue is that these young men have no idea about how real sex is, and instead assume one can have unlimited sexual power when engaging in real sex. This shows a disconnect between how real sex is and how Reboot users think real sex is like.

[Extract 12]: So actually a couple of months ago I had a chance to have sex with a girl that I liked for some time, and she was fairly good looking. It was 5 in the morning and I was quite drunk, and I have been able to get a half erection after she pleasured me orally. I blamed it on alcohol and tiredness. I felt shitty and embarrassed. She was quite disappointed as well as she really wanted me to (expletive) her (…). It was 80% at first, but as she continued my soldier started to shrink, and finally ended totally lifeless (No. 1, 23–24, 40–43).

[Extract 13]: I just broke up with a 25 year old girl who was more experienced than me. She was very attractive and wanted me BAD. I started to notice that I wasn't able to perform regularly (even though I found her attractive) and it got to the point where it was pissing her off and led her to cheat me. I felt depressed and less of a man because I couldn’t satisfy her hunger for me (No. 2, 146–150).

In fact, more evidence suggests that Reboot users assume that real sex is just like pornography: “I started watching more porn, as porn is the only thing that helped me get an erection and I was thinking I will be more in-control with her next time. All went in reverse of course.” The inability to have real sex to such a degree these individuals want was seen as harmful to their masculinity and watching pornography and not getting performance anxiety (since there is nobody to perform for) was a band aid for their damaged masculinity. Porn is not only a way of escaping reality, but also highlights that the individual masturbating to these videos for a prolonged amount of time display masculinity.

It also seems as if these users have low self-esteem. Take the comment down below :

Currently, I have no release, just these thoughts of insecurity and helplessness in my mind, telling me no matter how much money I earn, how much time I spend in the gym, how good clothes I wear I will never have an opportunity with an attractive girl. I am easily triggered to this state when walking around in the city and noticing hot girls (always measuring up their boyfriends, comparing them to myself and feeling lacklustre) (No. 12, 1130–1134).

In fact, this is to be expected as the overlap between r/NoFap and other forms of self-help have large overlap when overlaps between sub-Reddits are analyzed.

The overlap with religious sub-Reddits might explain the psychological distress among Reboot users. Moral issues with pornography but continuing to engage in watching it cause psychological issues, not pornography itself. The full paper is worth reading, but at this point it might become redundant.

Regardless, it seems as if NoFap is blaming the wrong thing, in this case pornography. Rather, the negative effects of pornography are due to individual issues, not pornography causally affecting individuals’ psychological and sexual well-being. If you want to try Nofap November, that’s fine! But do not expect positive effects because pornography use has ceased, pornography itself seems to be a neutral variable.

So, why do users who stop using pornography report positive effects? Simple: it’s a placebo. They just start putting more focus on themselves and improving themselves and see positive changes, but these changes could have been done even while porn was being consumed and they masturbated. All they’re doing is putting their time into other things, but none of this is indicative of pornography being harmful.

Straub and Schmidt (2022) attempt to show that abstaining from masturbation and pornography leads to better functioning, but again, this still fits into the moral-placebo framework rather than pornography itself actually being harmful.

In conlusion, No Fap has no scientific backing and most of the self-reported effects seem to be placebos as pornography itself is not causally associated with negative outcomes.

My own belief is that people who succeed on nofap are outliers. Only a small minority benefits from it, while most people are not going notice any effect. Of course, a subreddit about nofap selects for people who benefits from nofap (whether the effects comes from nofap itself, or from self-improvement in general). In addition, in my experience, these places are like cults. Go against their narrative one bit and you will be shamed and silenced (I guess they need the constant validation to stay on track).

The reason why I think nofap may benefit certain people for real is due to my own experience. I used to have an illness called postorgasmic illness syndrome. After having an orgasm, severe depression would creep up on me and last for up to a day. Then it would just spontaneously go away, like it was never there. When I made this connection, I started semen retention, and it made a huuuuge difference. I suspect many of the people who benefit from nofap also suffer from POIS.

One day my POIS just went away for whatever. I stopped feeling depressed after ejaculating. Because of this, my benefits from nofap vanished. I've tried going back to nofap more than once with the bias that it works due to how well it used to work, sometimes for almost a year. And nope, I can't detect any benefits. If there are any, they are so minor that I don't notice them. Anyway, me having been on both sides of nofap puts me in a nuanced and biased position imo.